By John Walsh

In this centenary year of the foundation of the state, one topic that has received little attention is the Irish language. For instance, none of the 50 essays in the Royal Irish Academy’s landmark publication Ireland 1922: independence, partition, civil war deals specifically with Irish, and it has not occupied any significant place in the Decade of Centenaries initiative. This is surprising, given the centrality of Irish in the cultural revival movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the role of members of Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaelic League) in the first independent government, leading to significant policy supports for Irish in the decades that followed.

SOCIOLINGUISTICS

So what has been the state of language policy over the past century? What have been the relative successes and failures of various government and civil society initiatives—for speakers of Irish throughout Ireland, for the Gaeltacht, for education, for legislation and for broadcasting? Language policy is a sub-branch of sociolinguistics—the study of the intersection of language and society—but also has links to other social sciences, ranging from sociology to governance. Emerging in the middle of the twentieth century, nowadays it is understood as some form of political intervention in a language situation, involving a range of actors spanning central government, local agents of the state and civil society. In the case of minority languages such as Irish, the ostensible aim is to strengthen the language (overt policy), but competing ideological currents (covert policy) may actually undermine the formal aims. A good example is the case of road signs: although Irish is constitutionally the national and first official language, it is in a smaller font and italicised on road signs, suggesting an inferior status. The time-line of the emergence of language policy is critical because the foundation of the Irish state pre-dated the academic discipline by about three decades, meaning that the policy-makers were operating with no specialist knowledge of the task at hand.

Irish has long been spoken throughout Ireland and the cross-border dimension has been a recurring theme over the past century. Although Irish was repressed under decades of Unionist government in Northern Ireland, it has resurged in recent decades, culminating in a successful campaign to force the British government to bring forward language legislation at Westminster. The current demography of Irish-speakers on both sides of the border is complex owing to different sets of census questions and ranges from relatively high percentages of daily speakers in the Gaeltacht to lower percentages elsewhere, often boosted by local community initiatives to support the language. Studying specific districts over time allows us to trace the changing fortunes of Irish; for instance, a study of the west Waterford Gaeltacht of Na Déise encompasses ethnographic insights provided by folklore collectors in the 1930s and the contemporary ‘language planning process’ aimed at boosting local use and knowledge of Irish.

From the eighteenth century, Ireland witnessed severe language shift from Irish to English. In 1922 less than one in five of the population had competence in Irish and most of its speakers lived in impoverished districts that came to be known as the Gaeltacht. The last century’s policy on the Gaeltacht spans milestone initiatives such as the establishment of dedicated institutions in the 1950s and recent sociolinguistic surveys highlighting the vulnerability of Irish as community language. A significant early language policy initiative was the Free State’s Gaeltacht Commission of 1925–6. Although some of the proposals were far-fetched, many worthwhile suggestions were blocked by the Department of Finance, itself led by former Conradh na Gaeilge member Ernest Blythe. This established a pattern in language policy that would persist over the decades: the Irish state expressing support for the revival but stopping short of measures that would make it a reality.

EDUCATION SYSTEM

For most people living in Ireland, their only contact with Irish is through the education system. Major policy initiatives since 1922 included the core status of Irish as a school subject and the rise or fall of Irish-medium schools from the 1920s to the current Gaelscoileanna, based on an immersion model familiar in many minority language settings. The period 1965–75 was significant because it marked the retreat of the state from the original policy of ‘Gaelicisation’ to a softer ‘bilingualism’. This culminated in decisions in the early 1970s to remove Irish-language requirements for the civil service and for passing the Leaving Certificate. As academic expertise in sociolinguistics developed, language policy showed signs of professionalisation during this time but there was a preference for avoiding robust policy decisions. In the early 1970s, the American sociolinguist Joshua Fishman strongly condemned the Irish government for its inaction on language policy. His target was foot-dragging over adequate resourcing of the Linguistics Institute of Ireland, whose hapless director, Fr Colmán Ó Huallacháin, later resigned in protest.

Civil society organisations, for instance Conradh na Gaeilge, have also played a critical role in language policy over the past century. Such activists fought ultimately successful campaigns in favour of Irish-language legislation in the Republic and Irish-language media. In the 1970s, an anonymous official in the Oireachtas Bills Office wrote draft legislation for Conradh na Gaeilge, based on best practice in countries such as Canada and Wales. Known only as ‘An Dréachtóir’ (the drafter) in the archives, the official smuggled out the bill unknown to superiors. It formed the basis of Conradh na Gaeilge’s campaign for Irish-language rights for decades, culminating in the Official Languages Act 2003 that provides for greater public services in Irish. The campaign for the Act reveals both the tenacity of activists and the hard reality of compromise to achieve broad policy aims.

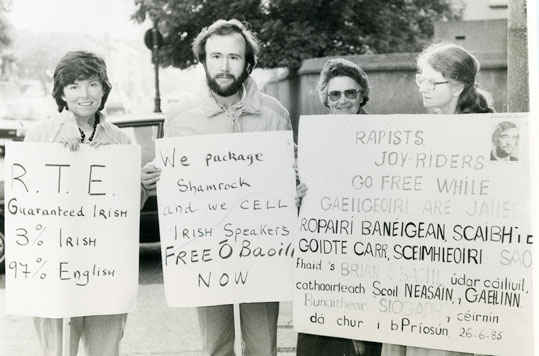

From the patchy provision of Radio Éireann to dedicated radio and television channels, the growth of Irish-language broadcast media is another key theme. Besides the well-known campaigns for Raidió na Gaeltachta and Teilifís na Gaeilge (now TG4), the last 40 years also witnessed the development of Irish-language community media, particularly radio stations in Belfast and Dublin. Taking advantage of the boom in pirate radio in Ireland at the time, Conradh na Gaeilge operated its own unlicensed station in Dublin in the late 1970s, while in Belfast an Irish-language pirate began broadcasting in 1985. In Dublin and Belfast today, Raidió na Life and Raidió Fáilte are licensed community stations acting as important media hubs for young speakers of Irish, many of them with little or no connection to Gaeltacht communities.

ROBUST LANGUAGE REVITALISATION STRATEGIES ELSEWHERE

Although Irish remains a core school subject, enjoys significant institutional support and a large minority has some competence in it, the core community that uses Irish regularly remains stubbornly small and is under severe pressure in the Gaeltacht. The nascent language planning process needs significant additional investment and there is an urgent need for greater work in areas such as digital media and introducing Irish to immigrants. The situation in the North remains fraught with considerable opposition to even basic protections for Irish-speakers. In the Republic, Irish occupies a marginal position in government and the policy outcomes have been mixed after a century of efforts. Recent growth of the minority language in other bilingual areas such as the Basque Country and Wales is instructive. Those countries, although lacking full independence, have adapted robust language revitalisation strategies from which Ireland could learn a great deal as we enter the second century of Irish-language policy.

Dr John Walsh is Associate Professor of Irish in the School of Languages, Literatures and Cultures at the University of Galway, and author of One hundred years of Irish language policy, 1922–2022 (Peter Lang).