By Stan Moore

Vexillology, the study of flags, reveals how deeply intertwined Ireland’s flags are with its history. This year, 2025, marks the 230th anniversary of the Orange Order and the enduring legacy of the colour orange in Ireland’s religious, cultural and political landscapes.

ORIGIN OF ORANGE

Orange began not as a colour but as a place, the principality of Orange in the Rhône Valley. The territory became part of the scattered holdings of the House of Orange-Nassau when William the Silent inherited the title ‘Prince of Orange’ in 1544. He led the Dutch struggle for independence against Spain in the sixteenth century, and his descendants became the Dutch royal House of Orange, a dynasty that endures to this day. His great-grandson, William of Orange, known in Ireland as ‘King Billy’, ascended the throne as King William III of England, Scotland and Ireland after overthrowing the Catholic King James II in the Glorious Revolution. His decisive victories at the battles of the Boyne and Aughrim in 1690 and 1691 established Protestant ascendancy in Ireland. Over a century later, when that dominance was challenged by the secular and republican United Irishmen, the Orange Order was founded in County Armagh in 1795 to defend Protestant supremacy. Thus the colour orange became a symbol of Protestant loyalty, in opposition to the green associated with the United Irishmen. Initially dominated by the Anglican Church of Ireland, the Order was staunchly anti-Catholic and even excluded Presbyterians at first, but as sectarian tensions escalated in the nineteenth century many Presbyterians joined its ranks.

PARADING AND PROVOKING

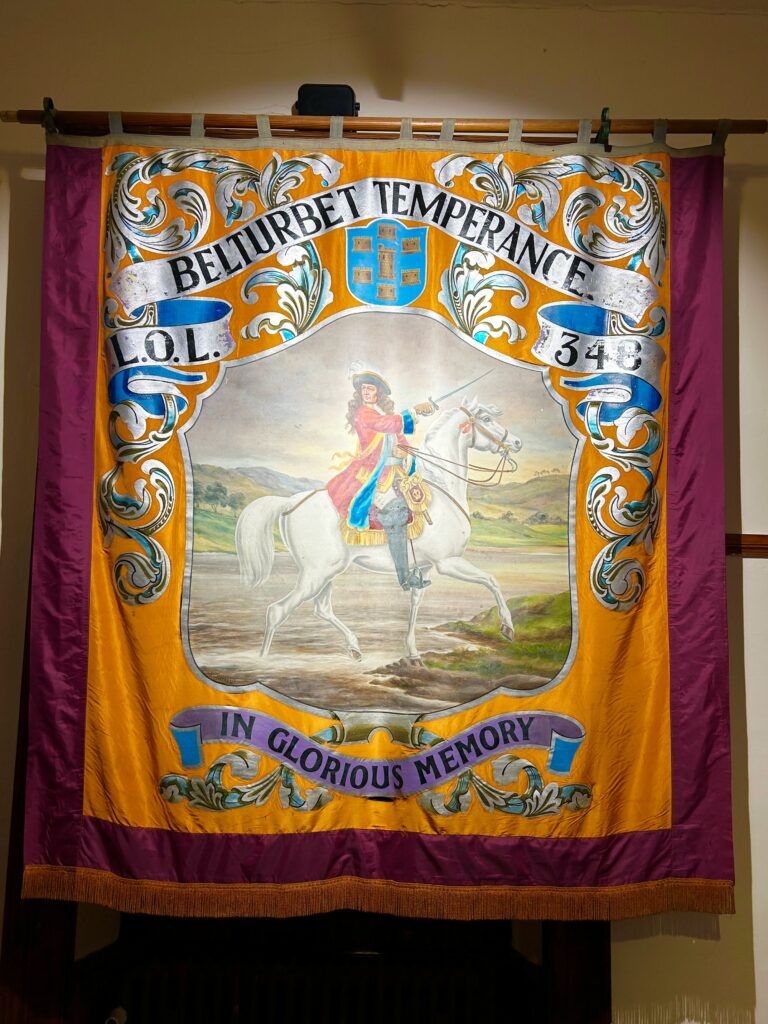

Ever since then the Orange Order has played a key role in establishing parading as the preferred method of public commemoration and celebration. The annual Twelfth of July marches serve as a public declaration of Protestant identity, reinforcing loyalty to the British Crown. Orange banners carried in these processions often depict ‘King Billy’ and biblical scenes, acting as visual statements of political and religious allegiance. Orange lodges, orange arches, orange lilies, orange sashes and other orange regalia have contributed to establishing the colour as both evocative for Protestants and provocative for Catholics. The history of orange in Ireland is inseparable from that of green, already established as the party colour of the United Irishmen in the 1790s, reflecting the island’s enduring divisions.

On the other hand, the two feuding colours also feature in calls for unity on certain issues. Ironically, the Orange Order was initially opposed to the Act of Union (since it abolished the exclusively Protestant Irish parliament) and in 1810 the Freeman’s Journal recommended ‘let Catholics and Protestants unite, let the Orange and Green be blended together’, and similarly in 1823: ‘thus may Orange and Green united appear’. In 1830 the Roscommon and Leitrim Gazette reported that

‘… there was an open meeting of some thousands of Orangemen and Roman Catholics on last Saturday at Shaneshill, between Portadown and Lurgan, to procure reduction of rents, and tythes and increase of wages. A large flag striped with orange and green was hoisted on the hill round which they assembled.’

TRADES AND TRICOLOURS

When Daniel O’Connell arrived back in Ireland after the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829, the Carlow Morning Post reported that

‘… from every vehicle orange and green banners, with appropriate devices, were exhibited; and there was scarcely an individual in the vast assemblage who did not wear orange and green ribbons … one might justly suppose that the return of Mr O’Connell was chosen as the period for the grand reconciliation of Irishmen—the Orangeman and the Catholic renounced their inveterate dissensions, and the colours which have been hitherto the emblems of the opposite factions, were blended together.’

As O’Connell made his way into Dublin, trade guilds arranged themselves to greet him. Here in the reports we find the earliest recorded mentions of the Irish tricolour. The pipe-makers displayed a ‘white silk trimmed with orange and green, bearing the motto, “Cead mille failte”, and “let brotherly love continue”; the men wearing green silk scarfs, tied with orange ribbons, and tricoloured cockades composed of orange, green and white’. The rope-makers held ‘a magnificent tricoloured flag, orange, green and white with gold trimming’, while the carpenters exhibited a ‘banner white, with orange and green border, bearing the royal arms’.

Traditionally Protestant-dominated, the guilds saw increasing Catholic membership. They held powerful economic and political influence and subsequently provided a network of support and fund-raising for O’Connell’s Repeal movement. While most Irish Protestants did not support it, a significant minority did. The inclusion of orange in its flags and regalia was an attempt to win over more Protestants and signalled the acceptance of a diversity of cultures. Emerging from this movement, Young Ireland was instrumental in establishing the green, white and orange tricolour as the Irish national flag when one of its leaders, Thomas Francis Meagher, brought one back from France as an explicitly republican flag modelled on the French tricolour—although not widely recognised as such until the early twentieth century..

COLOURS AND CONFUSION

Meanwhile, regional identity was being reinforced by the establishment of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) in 1884, ironically through the use of the county—an administrative unit introduced from the twelfth century onwards as part of the English conquest—as the main unit of competition. Thus GAA-based ‘county’ identities emerged with distinct jersey colours.

Despite its association with anti-Catholic sectarianism, especially in the North, Armagh GAA adopted orange and white as their county colours. At a Junior All-Ireland semi-final against Sligo in 1926, the Frontier Sentinel reported:

‘The appearance on the field of orange jerseys (which are a credit to the manufacturers at the Little Flower Knitting Industry, St Clare’s Convent, Newry) was the signal for an outburst of applause. It was interesting to note that the very harmonious colour was somewhat puzzling to many southerners, who frequently confound yellow with orange.’

Although the exact reasons for its adoption are unknown, it was likely aimed at dissociating the colour from Protestants. While the GAA is officially secular, historically its membership was Catholic and to this day the sport is mainly divided along sectarian lines in Northern Ireland. Probably owing to the associations with the Orange Order, for many years many Armagh supporters referred to the colour as ‘saffron’ rather than orange, despite Antrim’s playing in saffron, of yellow-orange shade, a colour inspired by the Gaelic Irish tradition of saffron-dyed clothing. The léine croich (saffron tunic) was once worn by Gaelic chieftains and gallowglass. The confusion over orange and yellow-orange can be seen in the Irish language, which originally did not have a distinct word for orange and simply used buí (yellow) to describe shades of orange. The word oráiste was only adopted when the fruit became more widely available from the 1930s onwards, but the term for a member of the Orange Order is still fear buí (yellow man). This can perhaps partly explain why historically some Irish tricolours had a yellow rather than an orange stripe. To this day some people still call the flag ‘green, white and gold’. The Irish government’s flag publication states that ‘sometimes shades of yellow or gold, instead of orange, are seen at civilian functions. This is a misrepresentation of the National Flag and should be actively discouraged.’ But this hasn’t stopped Offaly from playing in those colours since the 1920s. While an aversion to Protestantism may be a possible explanation, it may be that ‘gold’ sounds more poetic than ‘orange’.

It is also worth noting that green, white and gold are the livery colours of the green harp flag—golden harp with white or silver strings on a green shield (today the flag of Leinster). This emblem was first displayed in the form of a flag in 1642, when it was hoisted by the Irish rebel commander Owen Roe O’Neill over the ship St Francis while docked at Dunkirk in France. By the nineteenth century the green harp flag was considered to be the unofficial flag of Ireland, in opposition to orange. The Irish tricolour replaced it when it gained acceptance as the national flag after it was flown over the GPO during the 1916 Easter Rising, on what is now O’Connell Street. Ironically, the tricolour, which symbolises a union of loyalists and republicans, was adopted by the Irish Free State in 1922 after the partition of Ireland, which created the ‘Orange state’ that was Northern Ireland.

CONCLUSION

Irish history is complex and full of contradictions, and the colour orange is one such example. The presence of orange in Irish iconography, from flags to sports jerseys, reveals a delicate relationship between colour, identity and historical memory. In 1997 the Republic of Ireland football team introduced an orange away jersey which was not so well received at the time. It was then brought back in 2022, when it proved much more popular. A lot has changed since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, yet some things have not changed. Despite attempts at inclusivity, the orange colour still proves to be contentious. Although it was designed to include Protestants and unionists, many of them still see the Irish tricolour as simply a Catholic nationalist symbol and reject it altogether. The recent hijacking of the flag by far-right anti-immigration groups is ironic, since the flag was designed to represent unity, not division. If the flag is to fulfil its original purpose, it must be reclaimed as a reminder that Irish identity is, and always should be, open-ended.

Stan Moore is a flag and heraldry historian.

Further reading

D. Bryan, Orange parades: the politics of ritual, tradition and control (London, 2000).

G.A. Hayes-McCoy, A history of Irish flags from earliest times (Dublin, 1979).

N. Jarman, Displaying faith: orange, green and trade union banners in Northern Ireland (Belfast, 1999).

Irish Newspaper Archives.