By Brian Girvin

In his lifetime Owen Sheehy Skeffington (1909–70) was a remarkable figure. Though little known today, he was at the forefront of establishing liberalism as a major force in Ireland between the 1940s and the 1960s. This was an extremely conservative period in Irish life, but Sheehy Skeffington questioned and challenged Church and State as well as the petty (and not so petty) intolerances of post-Emergency Ireland. As early as 1945, he was described in the Irish Times as probably ‘our best controversial speaker’, alongside Seán Ó Faoláin, the editor of The Bell. He campaigned on a wide range of issues, was a founding member of the Irish Association for Civil Liberties and was an inveterate letter-writer (I estimate that he drafted more than a thousand letters to newspapers in his lifetime). If alive today, he would have been an avid and effective social media user (though a courteous one).

A SPECIAL FAMILY

Owen was born into the prominent Sheehy family. His grandfather was David Sheehy, Nationalist MP for South Galway and then for South Meath. David receives a mention in Joyce’s Ulysses when his wife Bessie meets Father Conmee SJ. Owen’s father, Francis Skeffington, was murdered by British forces during the 1916 Rising in Dublin, while his mother, Hanna Sheehy, was a lifelong feminist, radical and activist. His uncle, Tom Kettle MP, died fighting at the Somme in 1916. Conor Cruise O’Brien was a first cousin.

Though born into this well-placed Irish family, Owen’s life was not conventional. His parents embraced many radical causes, especially feminism, opting to use both surnames after marriage. They also brought Owen up without religion. He informed a correspondent later in life that ‘I am not a Catholic, and I never have been one’. His father was murdered when Owen was seven years old, and he and his mother remained close throughout her life. He often referred to her influence, on one occasion commending her wish to die ‘an unrepentant pagan’.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A LIBERAL?

Ireland was not a very welcoming place for liberals between 1940 and 1960. It had become more conservative and narrow-minded after independence. Despite this, it was also during these years that an alternative vision of Ireland gradually appeared—one that was tolerant, liberal and secular, promoting a progressive programme of change and reform. What set Irish liberalism apart from the dominant political culture was a concern for civil liberties, suspicion of Church and State and opposition to censorship. Liberalism also defended minority and individual rights against majoritarian conformity and the imposition of dominant (Catholic and nationalist) values. Irish liberals frequently identified with the republican-democratic tradition within Irish nationalism (but not necessarily with the IRA), on the basis of inclusiveness and equity. Liberalism was also anti-establishment on the grounds that the Irish state had not fulfilled the promise implicit in the campaign for Irish independence, although this legacy could be conservative as well as radical.

The liberal approach is well represented by Sheehy Skeffington when he appealed to Taoiseach Eamon de Valera for clemency in the case of Charles Kerins, who had been sentenced to death for the murder of a detective in 1944. Sheehy Skeffington maintained that the evidence against Kerins was ‘slight and circumstantial’. He acknowledged that ‘Denis O’Brien was murdered in cowardly fashion and that he got no trial at all. But this only becomes relevant if Kerins is proved guilty.’ Sheehy Skeffington believed that Kerins did not get a fair trial, a view shared by other liberal figures at the time. He subscribed to a defence fund for the condemned man but also condemned the IRA as ‘fundamentally fascist’ and its behaviour as ‘equally unsavoury’ to that of the Irish authorities. Nevertheless, as a member of Seanad Éireann, he reluctantly voted for internment in 1957, while also seeking assurances about the treatment of those interned.

DEFENDING CIVIL LIBERTIES

Many believed that Fianna Fáil had authoritarian tendencies, fearing for the future of the rule of law and civil liberties. Four issues galvanised opinion in the immediate post-Emergency period. The first was that the use of Special Criminal Courts undermined the rule of law and the right to a fair trial. The second was the government’s decision to prevent Noel Hartnett from broadcasting on Radio Éireann because of his political views, even though he was not a civil servant. The third was the high-handed and authoritarian actions of the minister for local government, Seán MacEntee, in dismissing the entire board of the Cork Street Fever Hospital. The fourth was the treatment of IRA leader Seán McCaughey, who died on hunger strike in appalling conditions.

These concerns led to the establishment of the Irish Association for Civil Liberties in 1948. The original circular appealing for support, drafted by Sheehy Skeffington, claimed that ‘The Democratic State can only survive if its citizens exercise constant vigilance; the history of the past few years has again proved this’. The Association’s aims were moderate and appealed to a wide and varied membership, including not only Sheehy Skeffington and Ó Faoláin but also Michael Yeats and Peadar O’Curry, the editor of The Standard, an influential Catholic newspaper. Over the next decade it was extremely successful in heightening public awareness about civil liberties. It promoted public debates on controversial issues, while at the same time it could attract government ministers to participate. The Association lobbied government departments and influenced policy-making from time to time. For instance, Fianna Fáil’s minister for posts and telegraphs, Erskine Childers, invited Sheehy Skeffington to provide detailed policy proposals on broadcasting reform after a public debate.

Though the Association occupied the moderate middle ground, this did not protect it from criticism. Maria Duce and other right-wing Catholic action groups accused it of being a front for communism. Garret FitzGerald, later taoiseach, published an article in an English magazine which ‘revealed’ that some political parties, two major newspapers and the civil liberties association had been infiltrated by communists, and that liberals were in effect well-meaning dupes of communism. The article was written in conspiratorial terms, but it also implied (if not alleged) that Sheehy Skeffington was a communist. While he was a socialist, Sheehy Skeffington was a fierce critic of the Soviet Union and its totalitarian supporters in Ireland. After legal action, FitzGerald withdrew all his allegations and published an apology.

THE ‘LIBERAL ETHIC’ DEBATE

Sheehy Skeffington played an active role in the Association for many years, for instance leading an investigation into conditions at the Bridewell Garda Station (described as atrocious for both gardaí and prisoners), but he also pursued a distinctive path as a controversialist and campaigner. In 1950 he engaged in a long and acrimonious exchange with Revd Professor Felim Ó Briain, an influential advocate of vocationalism, the Irish version of corporatism. Ó Briain condemned liberalism as a political philosophy, accusing it of moral nihilism and political weakness in the face of communism. Sheehy Skeffington responded by highlighting the writings of liberal Catholic thinkers while challenging Ó Briain’s assertions on grounds of fact and logic.

The ‘Liberal Ethic’ debate in the Irish Times ran for months, ranging far and wide while focusing on three major themes. The first was the confrontation between liberalism and Catholicism, including issues of tolerance and free speech. There was also a wide-ranging discussion of censorship in Ireland and its impact on the cultural environment. Another strand was opposition to Maria Duce’s campaign to amend the 1937 Constitution to declare the Catholic Church the one true church. Fianna Fáil TD Seán Brady defended the original wording of Article 44 as a reasonable and tolerant compromise, a view endorsed by a number of correspondents. Eamon de Valera was concerned at criticism of this article, and it is likely that Brady’s intervention was prompted by these concerns. De Valera’s office provided Brady with background material that was later included in his letters on the subject.

‘MOTHER AND CHILD’/CHURCH AND STATE

The ‘Liberal Ethic’ debate demonstrated that there was a small but vigorous liberal community in Ireland. Sheehy Skeffington received letters from various parts of the country complimenting him on his stand, though he also received critical ones. During the debate he had taken a cautious—if not defensive—stance in respect of the influence of the Catholic Church in Irish life. This changed in 1951, when Noël Browne resigned from government and published his correspondence with the hierarchy on the ‘Mother and Child’ scheme. Sheehy Skeffington actively supported Browne and his supporters during the 1951 general election and was identified as an important liberal influence by John A. Costello when writing to Archbishop McQuaid.

Sheehy Skeffington became far more critical of the Church, maintaining that one of the reasons for the fall of the Inter-Party government was ‘their willingness to consider the elected Parliament as an impotent, though highly expensive machine for ratifying the political decisions of the Bench of Bishops’. He reminded the bishops that their expertise in politics was limited and open to criticism, emphasising that ‘The people threw out the bishop’s supporters, and that Fianna Fáil was subsequently emboldened to bring in a compromise health scheme which dared to maintain some of the spirit of Dr Browne’s proposals’.

He extended this critique in a powerful review of Paul Blanshard’s The Irish and Catholic power (1953) in the Irish Times. Blanshard’s book offended Irish sensibilities, especially his claim that ‘the Irish Republic is a clerical state’. Dublin bookshops did not stock the book when published, and students in UCD had to obtain permission before they could read it. Sheehy Skeffington highlighted how Catholic power and influence had increased since independence, while recognising that not everyone would deplore that outcome. He used the opportunity to sketch out a liberal agenda, identifying issues that would become central to liberalism over the next fifteen years. These included a demand for non-denominational education, radical reform of censorship, and a rejection of the view that ‘Irish’ and ‘Catholic’ were synonymous. Sheehy Skeffington also highlighted the divisive impact of Catholic sectarianism on various inter-denominational and non-sectarian campaigns since 1945. More controversially, he drew attention to the negative impact of puritanical sexual attitudes on Irish life and society. The response to the review was at first overwhelmingly critical, though Sheehy Skeffington always responded trenchantly. It may be a coincidence, but he was explicitly mentioned as an enemy of the Church when Archbishop McQuaid established his ‘Vigilance Committee’ shortly afterwards to counter liberalism and communism.

THE SEANAD AND CORPORAL PUNISHMENT

However, 1954 was also a year of possibilities. Sheehy Skeffington was elected to the Seanad for Trinity College, Dublin, providing him with a national platform to campaign on many issues. In the same year, Tuairim was established as a forum for discussion and debate by Donal Barrington and Patrick Kilroy. While Tuairim was not explicitly liberal, it was tolerant, open-minded and non-denominational.

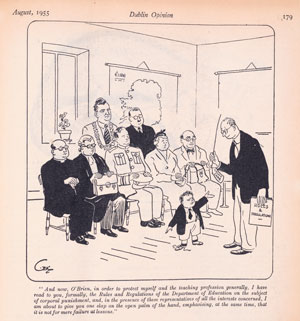

Sheehy Skeffington played an active role in the Seanad, regularly intervening on a wide range of subjects. He adopted controversial views on Northern Ireland, arguing that Unionism, not Britain, was the main obstacle to Irish unity. Anti-liberal sentiment was much in evidence when Sheehy Skeffington criticised the extent of corporal punishment in Irish schools. He condemned the Department of Education for refusing to apply the rules on punishment and was horrified by the many letters he received from parents whose complaints were ignored. The evidence he produced was met with incredulity, denial and anger. Two 1916 veterans, Minister for Education Richard Mulcahy and Senator Michael Hayes, defended the school system uncritically from a Catholic-nationalist point of view. Anti-liberal themes included the charge that the campaign was alien and foreign in origin; that the campaigners were anti-Irish and did not represent the Irish people; and that public discussion of this issue was not in the national interest. Mulcahy asserted that the campaign was ‘an attack by people reared in an alien and in a completely un-Irish atmosphere’. He condemned Sheehy Skeffington’s intervention, adding that ‘my only feeling is that it is a disgusting proceeding, deliberately and maliciously entered into by people who are not of this country or of its tradition’ (my emphasis). Despite this, Sheehy Skeffington continued to campaign for reform. He encouraged Peter Tyrrell to document the savage treatment he received in Letterfrack industrial school.

A MORE PROGRESSIVE PERIOD AND AN UNTIMELY END

Owen Sheehy Skeffington lost his Seanad seat in 1961, regained it in 1965 and was re-elected in 1969. By 1969 much had changed, and he was no longer an isolated liberal figure. The Labour Party had moved decisively to the left, embracing reform on many controversial matters. Even Fine Gael adopted reformist policies during the 1960s. Liberals were increasingly confident that progress could be made even on very thorny issues. In the Seanad, Sheehy Skeffington and John Horgan agreed to support Mary Robinson’s initiative to decriminalise contraception. Before it could be tabled, Sheehy Skeffington collapsed and died in June 1970. John Horgan believed that his death was a great loss to liberal and progressive politics in what would become a turbulent decade.

Brian Girvin is Professor Emeritus and Honorary Professor at the University of Glasgow.

Further reading

T. Finn, Tuairim, intellectual debate and policy formulation: rethinking Ireland, 1954–1975 (Manchester, 2012).

A. Sheehy Skeffington, Skeff: a life of Owen Sheehy Skeffington 1909–1970 (Dublin, 1991).

P. Tyrrell, Founded on fear: Letterfrack Industrial School, war and exile (ed. D. Whelan) (Dublin, 2006).

G. Whelan (with C. Swift), Spiked: Church–State intrigue and ‘The Rose Tattoo’ (Dublin, 2002).