By Brett Bowden

I have a friend who likes forwarding bits of internet advice. One nugget of wisdom sticks in my mind: ‘Yesterday is history. Tomorrow is a mystery. Today is a gift. That’s why it’s called the present.’ Catchy, perhaps, but that is not why it’s called the present. Advice about ‘living in the moment’ abounds; a quick search offers up the likes of ‘The Art of Now: Six Steps to Living in the Moment’ and ‘Ten Tips to Start Living in the Present Moment’. Apparently, putting the past behind you and living in the moment is the secret to happiness and success—except, for most people, the key to a contented life isn’t hiding in a slogan.

What does this say about Janis Joplin, who was prepared to trade all her tomorrows for one more yesterday with her beloved Bobby McGee? What about historians, archaeologists and the like? Are we written off as lost causes because we dwell in and on the past? Personally, I’m sceptical about the prospect of living without reflecting, considering what might have been done differently, lessons learned from past mistakes. Even better, lessons from not making mistakes.

One of the more interesting quotes about living in the present comes from Henry David Thoreau’s Walden: ‘The meeting of two eternities, the past and the future … is precisely the present moment’. While it sounds nice lyrically, the idea of the present being a meeting-point between two eternities was thought to be just that—a lyrical idea.

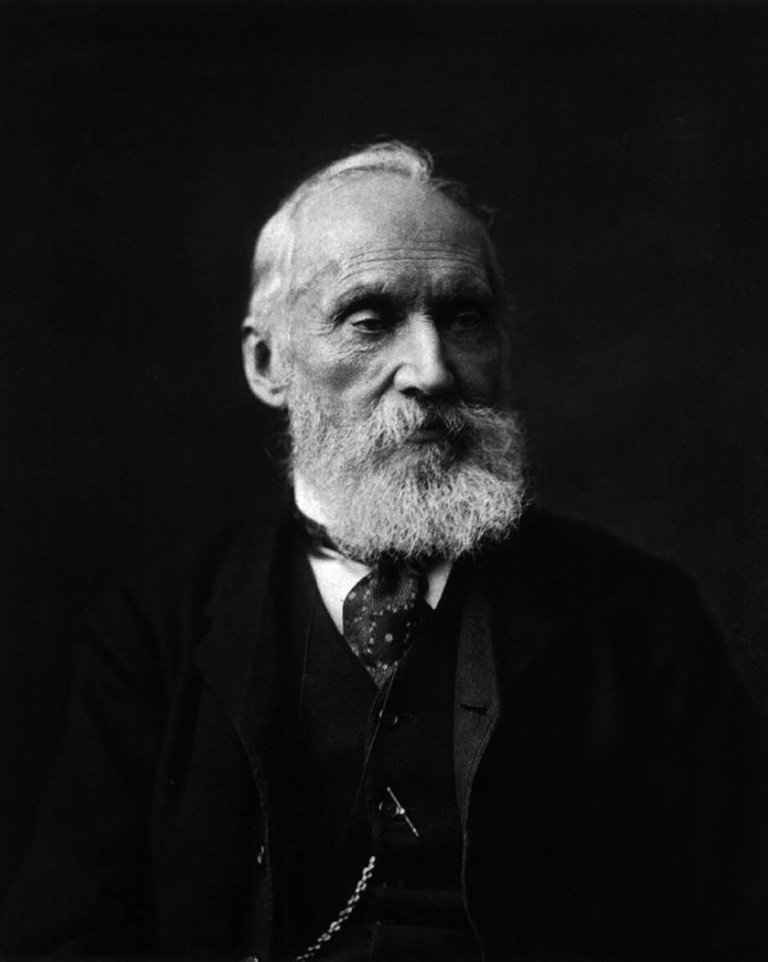

In the year Walden was published, 1854, across the Atlantic Belfast-born mathematician William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) told a gathering at the Royal Society of Edinburgh ‘that sunlight cannot last as at present for 300,000 years’. The clock was running down on the future of humankind, and he was convinced ‘that the end of this world as a habitation for man, or for any living creature or plant at present existing in it, is mechanically inevitable’. There was no eternal past and, more concerning, no prospect of an eternal future.

Claims like those of Lord Kelvin, a future president of the Royal Society, gave scientific credence to long-standing beliefs in Christian Europe that the end of the world was indeed nigh. Both time’s beginning and time’s end were said to be much closer to the present than is now known to be the case. Earth is actually around 4.54 billion years old, while the slightly older Sun will continue to burn for at least that long again, and yet our mind-set remains largely unchanged.

The significance of the present and the relationship between past, present and future have intrigued for centuries. St Augustine mused at length in his Confessions, concluding that ‘neither the future nor the past exist’. Rather, he thought, ‘there are three times, a present of past things, a present of present things, and a present of future things’. For Augustine, the ‘present of past things is memory; the present of present things is direct perception; and the present of future things is expectation’.

Given that the present is seen as the junction between past and future, it’s not surprising that it figures so prominently in our thinking. In fact, François Hartog suggests, the ‘category of the present has taken hold to such an extent that one can really talk of an omnipresent present’. He thinks that we are trapped by a ‘collective inability to shake off what is generally called “short-termism” … the sense that only the present exists, a present characterized at once by the tyranny of the instant and by the treadmill of an unending now’.

My concern is with more than just our obsession with the present: it’s the sometimes implicit, often explicit, assumption that the present is better than the past and the future—and not just better but morally superior. Some measure of this is not entirely surprising, given the widespread faith in the idea of progress, according to which the present should be an improvement on the past, but it’s more difficult to explain why the same holds for the future.

Why do we think now is so special? A turning-point in history. The End of History. Worthy of a new geological epoch—the Anthropocene. Something so significant and so obvious that we can declare it and name it now. There’s no need to wait for the passage of time for a bit of perspective, the benefit of hindsight.

A possible factor is the unique set of circumstances that make life on Earth possible. To the best of our knowledge, they are circumstances not replicated elsewhere in our solar system, or the Milky Way galaxy, or even the known universe. To be in both the here and the now against such astronomical odds—how can it not be special?

Similarly, humans are largely self-preoccupied beings. Against the odds, the line of evolution has led to us, and we tend to lack the capacity of foresight to see where it might go in the future. We can’t help but be impressed by our list of accomplishments, both discoveries and inventions, particularly in the past few hundred years. This renders us blind to what our descendants might be capable of achieving long into the future.

Even for the most imaginative, artificial intelligence, bio-implants and cloning are double-edged swords. Speculations on the future, near and distant, are overwhelmingly dystopian or post-apocalyptic in nature. Sure, some might involve space travel and form-fitting one-piece suits but, largely, literature and cinema are obsessed with a future where progress has violently come to an end and the human condition has regressed from the heights of now to its more primitive roots, eking out a living in some kind of Hobbesian survival mode.

Persisting with the blinding belief in the superiority of now over a savage past and a dystopian future severely stunts our thinking and imagining about what lies ahead. We have great faith in the idea of progress, are convinced that humankind is steadily improving, and yet can we really be so vain as to believe that we have reached the end of the line?

The focus here, though, is the present—now—and our overwhelming inclination to declare all too prematurely its significance in the bigger picture. The future becomes important when it is the present, a vantage point from which to look back on and reassess the significance, or otherwise, of the historical now.

If one is walking in the woods and uncertain of one’s location, not lost but unsure of one’s bearings, one of the most effective ways of situating oneself is to find higher ground to work out one’s position in relation to known landmarks—the carpark, for example. In such a scenario, what one is looking for is perspective on one’s present location in relation to other locations, with the relational aspect being key to removing uncertainty. In a similar way, a peak, be it a hill or a mountain, can seem like the top of the world when you are standing on it—that is, until you look around and see that the next peak is higher again, and the next even higher still. The same basic principles apply just as well to the temporal domain as they do to the spatial domain. All too often, the present is a peak that we assume to be the highest, without taking the time or trouble to look to the past, or speculate on the future, for some much-needed relational perspective.

Brett Bowden is Professor of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry at Western Sydney University and author of Now is not the time: inside our obsession with the present (iff Books, 2024).