RTÉ1 & BBC1, 17 March 2025

By Sylvie Kleinman

‘A little over 1,500 years ago, the wild western land of Ireland was believed by many to be the edge of the world. To this strange land travelled a man, intent on transforming its people. His name was Patrick …’ Thus begins the exaggeratedly aerial voice-over of Patrick: A Slave to Ireland. Spectacular views carry us appropriately over the sea to the edge of the Irish coast, with Croagh Patrick as the majestic backdrop. This is a mostly robust retelling of Patrick’s own story, enmeshed for all times with that of the pagan Irish receiving Christ’s mission and spreading the word beyond their shores.

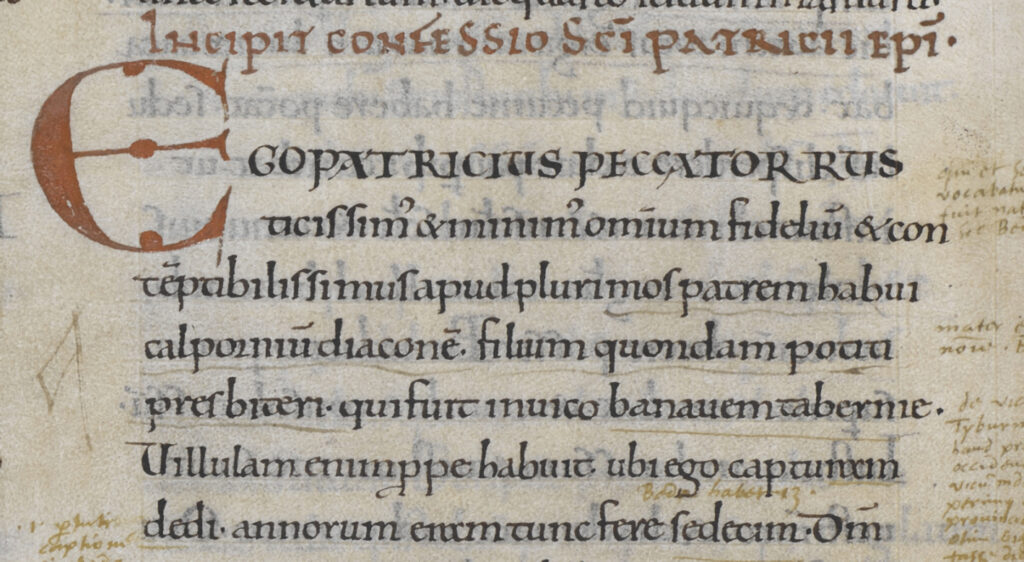

Despite some irritating production features, this probing effort challenges the St Patrick of ‘myths and legends’, constructively moving beyond his titanic battles with snakes and druids. This film is a familiar, odd fusion of scholarly insights woven around an occasionally dumbed-down script and romanticised (silent) re-enacted scenes. Yet it relocates him in his genuine historical context, to ‘reveal who this man truly was’. An essential dimension to this process (which also enabled his medieval hagiography) is foregrounded at the outset, as we hear Patrick in his own words: ‘I am a sinner, a simple country person, looked down on by many’. Unlike innumerable Christianisers and pillars of the early Irish church, we have direct insights through primary sources into his character and motivations, as in his old age he composed first-person writings (c. 470s?). On screen we saw his iconic soul-searching Confessio, available on the Royal Irish Academy’s rich online resource at confessio.ie. Infuriatingly vague on the facts of history but rich in biblical metaphor, it is appealing and beautifully mystical. Patrick reflects on his trials and on experiencing God’s divinity, overviewing his evangelising mission in Ireland. Later copied into the Book of Armagh, his texts enabled Muirchu and Tírechán in the seventh century to compose hagiographies. These broadcasted the attributes and supposedly single-handed achievements of Patricius, relaying their adventure-filled veneration to posterity.

Patrick was depicted on screen by a costumed actor (Dmitri Vinokurov) trudging purposefully through the island’s dense forests, or proselytising and baptising small groups of eager and attentive Hibernians. His attire seems well researched, but that he had been blonde, hair and beard trimmed to respectable lengths (and far from unappealing), we cannot say. There were more familiar images of him as an older, mitred man with a lengthy beard. A few lively-worded reviews in the press came down harshly on how spotlessly clean he and his garments remained, despite the rigours of trekking and sleeping out with the wolves. The soaring dramatic music is often overbearing—we know this is ‘epic’ without it. As with other documentaries, there is an irksome disconnect between the (mostly) sharp scholarly perspectives and the over-simplified narrative. An eminent actor (Ciarán Hinds) reading the voice-over is always a plus, but his enunciation is sometimes strained, his tone often more suited to a toddler’s story-time. Patrick’s life is recounted in tight linear fashion. A Briton by birth who originally came here as a slave but escaped, Patrick was then inspired by studying St Paul. Guided by nocturnal visions, he prophetically heard Irish voices calling him back. He returned with zeal to make the c. 400,000 souls in Ireland children of the Lord in 432. The more he could convert, the sooner our Saviour would return, but we were nearly halfway through watching him dutifully going about before being told that ‘he was not alone’. Christianity was spreading in Ireland for ‘another reason’, because there had been ‘others before’, like Declan. Most evidently, Palladius had been sent as the first bishop in 431, the first recorded date in Irish history. This proximity seems too convenient, and he was airbrushed out of the seventh-century Patrician epics.

There were some enthusiastic (if cringing) attempts to give contemporary relevance to Patrick, a ‘non-native’ who had experienced trauma and enslavement but also started a writing tradition perhaps heralding James Joyce and Sally Rooney. This reviewer prefers to ponder whether, as claimed in the promotional blurb, he had actually performed macro-historical feats such as uniting ‘the divided Irish tribal kingdoms’ in their new culture, and whether Christianity would not have spread anyway, as it had already been introduced. There is an interesting class element, as he was not a prole and converted some high-born women. In any event, his agency and game-changing capacities are immutable, and many critical perspectives challenge the conventional narrative. The development of ecclesiastical structures and monastic settlements after Patrick is clearly explained and usefully visualised with maps and shots of relevant sites. Given the fact that records and cartography had not been introduced here by the Romans, it was interesting to see the packed map of holy wells and the very familiar outreach of Irish Christians into the British Isles and the Continent. Tourism Ireland (and Arte) were involved, and unsurprisingly this is quite an exportable visual experience, namely the sweep over Croagh Patrick to the raw edge of the known world. With not an illuminated parchment in sight, the so-called barbarians had embraced their new faith in this awe-inspiring location. We recall Daniel O’Connell’s claim that God had created Ireland.

The producers wisely stuck to their brief and did not overstretch or ram too much at us. But reconstructing through the centuries the status and popularity of Patrick and his promotion of the Trinitarian shamrock would make a compelling topic. There were the predictable shots of contemporary parades and day-glo green lycra, but anyone aware of his prominence in the visual culture of the 1780s would have recognised the painting depicting him nobly chasing away druids. It is a panel by Vincenzo Waldré on the ceiling of St Patrick’s Hall in Dublin Castle, an odd name for a ballroom, which at this time also became the space for the investiture of the Knights of that name. Commissioned c. 1787, it embodies the appropriation by Anglican colonial élites of this potent symbol to counter the patriotic buzz of the Volunteers. But a new Irish identity was spreading like wildfire, and by then a beloved Paddy had become everyone’s ‘Papa’, both sacred and secular.

Sylvie Kleinman is Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of History, Trinity College, Dublin.