National Gallery of Ireland, Beir Wing, Rooms 6–10

Until 22 February 2026

By Donal Fallon

In the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Ireland, a work by the artist Michael Farrell shows a meeting of James Joyce and Pablo Picasso at the famed Café de Flore in Paris. The idea of the two regulars crossing paths there fascinated Farrell, who found much inspiration in Joyce as the model exiled Irishman in la ville lumière. He would return to the meeting of the men time and time again in his practice. While such a meeting likely never occurred (‘Joyce never mentioned that unlikely party to me’, was allegedly Samuel Beckett’s reply to Farrell’s enquiry), both would transform their respective creative fields forever from the city in which they created their masterpieces. There is no understanding of Joyce or Picasso possible without an understanding of Paris, the city from which this show has its origin.

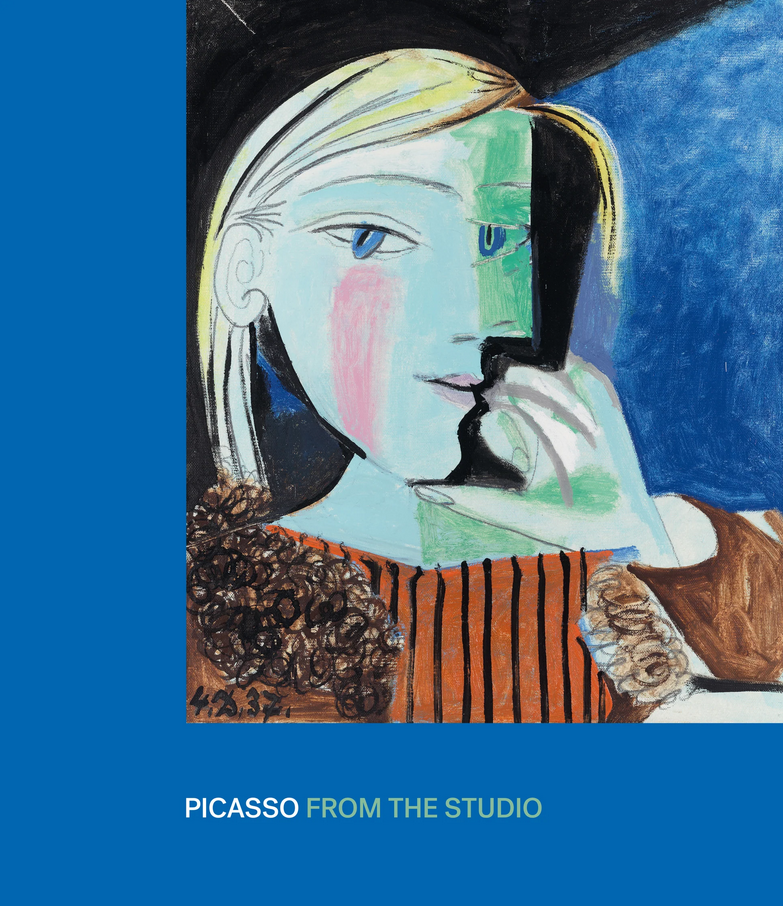

In his lifetime, there is general agreement that Picasso created at least 50,000 works of art. Drawing almost exclusively on materials now housed at the Musée national Picasso–Paris, this show brings focus to the subject by examining output in the context of a number of his studios, beginning with the arrival of the young artist in Paris at the start of the twentieth century and ultimately bringing us to Mas Notre-Dame de Vie (1961–73) in Mougins. In each environment we see that Picasso was shaped by his immediate locality in ways that influenced not only his subject-matter but the medium through which he expressed himself.

Picasso’s 1937 Guernica is a work that went on quite the journey in its early days, and which has also had an extraordinary afterlife. In northern England, the Manchester Foodship for Spain displayed the work in the Nunn & Co. Ford automobile showroom as part of their fund-raising efforts for the beleaguered Spanish Republic. The Manchester Evening News told its readers that ‘no-one could fail to be impressed by a tremendous work which, more than any words, condemns the crime of war’. Like Delacroix’s La Liberté guidant le peuple, the work has been reimagined and reinterpreted for different times. In Catalonia, artists repainted the work in the colours of the Palestinian flag in recent years in a large-scale protest. In a Belfast cross-community project, spearheaded by Danny Devenny and Mark Ervine, the work appeared as a mural in 2007 as a statement against violence and war.

We encounter Guernica in this exhibition, but through the camera of another artist, Dora Maar, photographer and Picasso’s lover, who tracked the creation of the work in a series of black-and-white images, which play on a screen. The evolution and transformations of the work are clear, though Picasso himself preferred the term ‘metamorphosis’. Maar’s relationship with Picasso grew strained and distant; famously, she would remark that ‘All his portraits of me are lies. They’re all Picassos. Not one is Dora Maar.’ Within this exhibition, we quickly learn that Picasso felt it important that his work be documented by others. Lee Miller—herself currently the subject of an extraordinary retrospective in London’s Tate Gallery—is another chronicler of Picasso on the walls here. We learn that Miller photographed the artist more than 1,000 times, while he painted six portraits of her. What makes this show so unique, however, is not merely the clever inclusion of the work of others in documenting the artist at work but also the fact that the main body of work comes from the collection of the artist himself. As a visitor joked, ‘Picasso was clearly the greatest collector of Picassos’.

Picasso’s politics emerge throughout the exhibition. Painting, he would insist, was not a medium created only to decorate apartments but ‘an instrument for offensive and defensive war against the enemy’. Other mediums of art offered different opportunities. We learn that, ‘in keeping with his Communist beliefs, Picasso hoped that his ceramics would be accessible and affordable’. Yet he managed to live a frugal but relatively normal life during the Nazi occupation of France, despite his classification as a ‘degenerate’ artist, which forbade him from displaying his art. Jan Flann, author of a shared biography of Picasso and Matisse, notes that ‘early in 1942 rumours circulated, and even reached New York, that Picasso had been committed to an insane asylum’. It was a time when the artist remembered that ‘there was nothing else to do but work seriously and devotedly, struggle for food, see friends quietly, and wait for freedom’. Lore has it that on visiting Picasso’s studio and residence a German officer looked at a postcard of Guernica and asked, ‘Did you do this?’ Picasso replied, ‘No, you did’.

Beyond politics, the insights into Picasso’s personality are just as interesting. Obsessions could come from the most surprising places. In Vallauris, winning a goat in a local lottery created a situation whereby he ‘indulged his new pet and let it roam freely in their home regardless of the chaos it created. Goats began to feature in his paintings, sculptures and ceramics.’ Later, while recovering from surgery, a fondness for the novels of Alexandre Dumas led to a fascination with musketeers, whom he ‘painted repeatedly in different guises’. A painting of a guitar-playing musketeer is one of the most striking in the exhibition, holding the gaze of visitors.

Given the scale of Picasso’s output, his presence is a near-certainty in every European national gallery, but this exhibition offers a rare chance for the Irish public to see him in less-familiar form, with large-scale bronze works appearing alongside ceramics. Following on from the successful exhibition of work by Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone, Ireland’s own early pioneers of cubism, Picasso: From the Studio is another ambitious undertaking from the NGI. Praise is due for the continued practice of offering free admission to exhibitions on a Wednesday morning. Picasso ultimately wanted his work to be seen by as many people as possible, and every indication is that the Irish public have proven to be an eager audience.

Donal Fallon is a historian and presenter of the ‘Three Castles Burning’ podcast.