National Print Museum, Haddington Road, Dublin D04 E0C9

https://www.nationalprintmuseum.ie

By Donal Fallon

Industrial and craft museums are rare in Ireland, which means that stepping into the National Print Museum is an immediately different experience from most spaces explored in this column. On a busy floor, laid out like a traditional print-shop, various machines are doing their job before impressed visitors. There’s even a Wharfedale Stop Cylinder Press, the type of machine used to bring the 1916 Proclamation to life. The story of that document brought this museum to greater prominence against the backdrop of the Decade of Centenaries, reminding us that, while Patrick Henry Pearse may have read the Proclamation, Christopher Brady and his small team made it a physical reality in Liberty Hall on the eve of insurrection.

The National Print Museum is keen on moving to a new home, emphasising that ‘we are a living museum. As such, we need to conserve the collection, ensuring its full working order, and preserve the associated stories and craft of printing.’ Its little corner of Beggar’s Bush Barracks has served it well, but the sheer scale and physicality of its collection means that space is paramount, and more is required. Despite the slightly cramped feeling of its current home, this exhibition draws on the landings over the main space perfectly, reminding us that the histories of print and design are inseparable. It is an entirely unique experience to gaze on beautiful posters of yesterday to the sound of the machines working below.

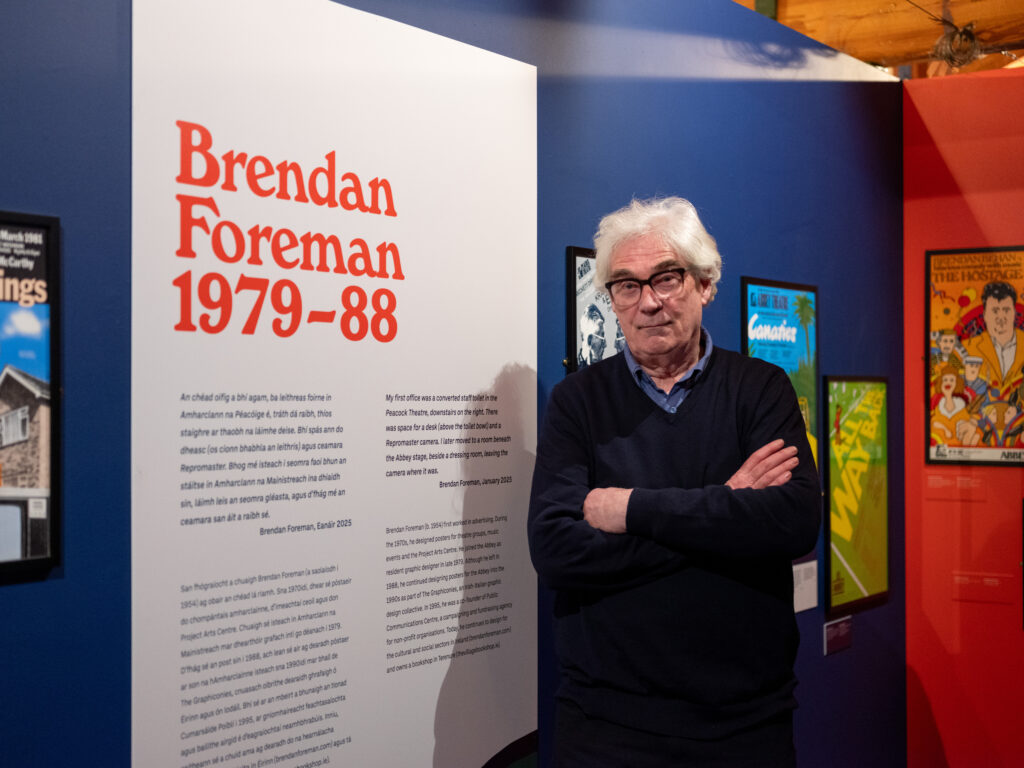

Curated by Linda King of the Institute of Art Design and Technology (IADT), Poster Boys brings together the work of designers Kevin Scally and Brendan Foreman for the Abbey Theatre. Bilingual throughout, the exhibition consists not only of posters from the archive of the theatre but also personal recollections of both designers. Dividing the work of the two artists into separate spaces, we are invited into their own histories as well as that of the theatre for which they worked.

Besides the finished product, there is a strong emphasis on process. We learn early on that ‘a poster took about two weeks to produce—from sketch to final print. In the 1970s and 1980s, a print run was around 200–500 posters. The majority were hung in pubs and cafés around Dublin.’ These expertly designed works could feel ephemeral in their own time but, like gig posters, are now much lamented in a city with an increasingly digitalised advertising landscape.

From the very outset the Abbey Theatre placed importance on aesthetics. Yeats recruited the artist Elinor Monsell to create a logo for the theatre, and the woodcut of Queen Maeve hunting with her wolfhound has proven one of the great enduring visuals of the Irish arts world, with updated versions appearing around anniversaries in 2014 and 2024. Still, it would be 1972 before the theatre hired its first in-house graphic designer, Kevin Scally. Seven years later Brendan Foreman succeeded him.

That both men enjoyed a strong degree of artistic freedom is clear throughout. Inspiration could come from unlikely places; a 1978 poster for Hugh Leonard’s Stephen D references Andy Warhol’s screen prints, showing the actor Barry McGovern against contrasting colours. Today theatres and cultural institutions often seek an instantly recognisable design formula, but the sheer diversity of design approaches from Scally and Foreman are a joy to explore.

Foreman notes that in 1981 alone he designed 27 posters between the Abbey Theatre and the Peacock. Insight into the time-consuming nature of the work comes with a design for a production of The Hostage, where we see Foreman’s preliminary sketch alongside the original artwork separations. Rubylith, we learn, ‘is a red-coloured, photo-masking film used to produce individual colour separations for printing silk-screen or offset-lithography’. Beyond design, a mastery of colour and printing practice was vital, too, to ensure that the finished product reflected the vision of the concept.

Posters were collaborative by nature, Scally recalling that directors would develop their own unique interpretation of the play being performed, and how ‘through discussion with them you try to capture that interpretation in the poster, which becomes its first visual presentation on the street to the future audience’. Collaborations occurred with printers too. A map illustrates the location of printers who worked with the Abbey Theatre, noting that the displayed posters provide ‘a valuable record of specialist printers’ in the city. Almost all are now gone. While theatres and other cultural institutions now focus their advertising efforts on the digital realm (you’re more likely to encounter a play advertised on Instagram than in your local café), the Abbey continues to work with designers and to produce visually striking posters.

Leaving the National Print Museum, a quick detour to the small shop demonstrated one of the innovative ways in which the institution engages with the printing and design communities today by creating limited-edition prints responding to exhibitions and themes in the museum. As part of Poster Boys, both artists were invited to produce a new work coinciding with the exhibition. Scally’s print, Chair No. 14, is a representation of his kitchen table, at which much of his designing work occurred. Foreman’s print plays on Monsell’s 1904 woodcut, showing a torn paper effect upon it, reminding us of the ‘ephemeral life of a poster’. Printed by letterpress on the museum’s Vandercook printer, both are beautiful works in their own right that allow the visitor to take something striking home.

Donal Fallon is a historian and the presenter of the ‘Three Castles Burning’ podcast.