By Gabriela Lojewska and Philip McEvansoneya

The exhibition of Polish art that took place in Dublin in 1937 was a doubly significant event. First, it was an episode in the wider campaign of the new Polish state, the Second Republic, founded in 1918, to mark its arrival on the international stage as an independent nation through cultural diplomacy. Second, it was unprecedented in Ireland as a free-standing event dedicated to Poland that brought together old and modern examples of fine art printmaking and contemporary textile design.

The Second Republic was the revival and embodiment of Polish national fortunes because, from the end of the eighteenth century until the end of the First World War, Poland had been partitioned and the Polish language and culture repressed by Prussia, Russia and the Hapsburg Empire. Despite the partition, over the course of the nineteenth century there was a progressive consolidation of Polish cultural identity. In late nineteenth-century Ireland and Poland alike, cultural nationalism thrived while each remained under external political control.

‘SOFT’ DIPLOMACY

After 1918, cultural (or ‘soft’) diplomacy, meaning the international communication of all aspects of culture but especially art, literature and music, became all the more common, especially by newly independent countries such as Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. Against the backdrop of deteriorating international relations in Europe in the mid–late 1930s, cultural diplomacy was a way of making connections, gaining influence, developing commerce and promoting tourism; it could precede or support or be the public face of formal diplomatic relations.

A strategy was adopted to portray Poland as an ancient nation and a modern state with a distinctive culture. This led to the mounting of a series of exhibitions that were sent to foreign venues, primarily in Europe but also as far afield as the United States and Japan. The exhibitions included representative examples of historic and contemporary Polish art, especially original prints, and contemporary crafts that collectively showed a distinct national style. In the interwar period many nations sent and received such officially sanctioned exhibitions. These unilateral or bilateral events were in addition to large-scale international events, such as the Exposition Internationale held in Paris in 1937, that were the descendants of nineteenth-century great exhibitions.

SOCIETY FOR THE DISSEMINATION OF POLISH ART ABROAD (TOSSPO)

Dublin was the destination for one of the peripatetic shows that were selected and overseen by Towarzystwo Szerzenia Sztuki Polskiej Wśród Obcych (TOSSPO), the Society for the Dissemination of Polish Art Abroad. TOSSPO was set up in 1925 under the Ministry of Religious Beliefs and Public Enlightenment and was soon under the day-to-day control of Mieczysław Treter (1883–1943). By 1939 it had organised more than 80 exhibitions in 28 countries but, inexplicably, Ireland is omitted from the lists of TOSSPO events. TOSSPO also brought reciprocal exhibitions, from which Ireland is again absent, to Poland. TOSSPO pursued ‘propaganda of Polishness by art in foreign exhibitions’, as Treter put it. The exhibition was therefore brought to Dublin with the involvement of the Polish consul-general, Wacław Tadeusz Dobrzyński (1883–1962).

In addition to his diplomatic skills, Dobrzyński, who had been in the post since 1929, was highly cultured and well connected with the art world in Ireland. For Dobrzyński, nations and the relations between them were built on culture. Being committed to the idea of cultural diplomacy, he arranged that the exhibition of Polish art and design that had been shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1936 would come to Dublin at the beginning of 1937. The exhibition was intended to bring Polish art and design to public and critical exposure, and to show that the arts in general were fostered by and represented the new state.

INTERWAR REVIVAL OF PRINTMAKING

Historically, there were few practical links between Ireland and Poland. An exhibition by the Polish printmaker Stefan Mrozewski (1894–1975), who was already successful in England, was briefly held in Dublin in 1935, but Polish art remained largely unknown. Polish printmakers were closely involved with the wider revival in the interwar period of printmaking, especially those made from woodblocks. Warsaw was the venue for the first and second international exhibitions of original wood-engraved prints held in 1933 and 1936, but the woodblock print revival rather bypassed Ireland.

The traditional aspects of Polish printmaking did not mean stagnation or anachronism but rather the revival and modernisation of established forms and techniques, especially working on wood. Artistic forms of cultural expression in the new state were held to be authentic, as they were engendered and legitimised by inheritance from the national past. Traditionalism was a counterweight to the adoption by many Polish artists of modern French or German artistic forms. Treter promoted art that was different and typically Polish. This was supported by Władysław Skoczylas (1883–1934), the leading Polish printmaker of his day and the main teacher of the following generation—effectively the founder of a new school of Polish woodcut—and another of the instigators of TSPO.

The Dublin exhibition did not take place in conjunction with any other organisation. It was held in January 1937 at Mills Hall in Merrion Row. The exhibition was in three parts. First, there was a small but prominently displayed selection of copies of old prints that had been rediscovered as recently as 1921, the originals of which dated mainly from the eighteenth century and therefore had pre-partition origins. As examples of folk woodcuts, their awkward but expressive form and primitive techniques were seen as evidence of their authenticity. Prints of this type were among the earliest works of art to be exhibited abroad by the independent Polish state; they were the bedrock of Polish printmaking traditions. The second part was a large selection of modern prints in various techniques, including work by leading Polish artists (see below). The third consisted of a number of kilims, handwoven carpets, that incorporated modern versions of traditional designs. Kilims were an important craft product and were promoted as a distinctive national form. Along with prints, they were frequently included in the Polish contributions to international exhibitions and were present in the majority of exhibitions circulated by TSPO.

IMPORTANT SOCIAL EVENT

The opening of the exhibition was something of a social event and there was a good turnout of artistic, diplomatic, legal, literary and political Dublin (Éamon de Valera was invited but could not attend). Art and diplomacy were combined in both the literal and figurative senses. Among the artists were George Atkinson of the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, Dermod O’Brien, the president of the Royal Hibernian Academy, Sarah Purser, Estella Solomons and Jack B. Yeats. The political and diplomatic attendees included the government politician Patrick Little, later the first chair of the Arts Council of Ireland; the minister and other members of the American legation, plus Col. Theodore Roosevelt Jr, who was then visiting Ireland; the French minister; the chargés d’affaires of Belgium and Germany; the consuls-general of Italy and Switzerland; the Canadian trade commissioner; the Portuguese consul; and various honorary consuls. This suggests Dobrzyński’s power to attract an illustrious crowd, but it may also be evidence of the ritual aspects of diplomatic life in a capital of less than front-rank standing, as may be seen from the prevalence of non-ambassadorial titles. More importantly, informal personal contact on the margins of cultural events was held to be one of the most effective means of promoting state aims.

The chronological range of the prints was broad enough to convey the history and continuity of printmaking, but the bias was towards younger artists to show a flourishing aspect of modern Polish art. There was a balance of male and female artists among the 47 participants. A few examples from 150 works displayed will serve to indicate the range of subject-matter, the variety of styles and the different media exhibited.

SOME EXAMPLES

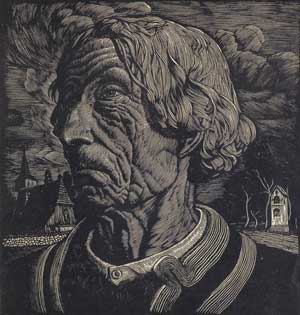

Unsurprisingly, given his influence and high status, there were as many as fourteen works by Skoczylas, chief among them being Goral. The Gorals, an ethnic group of the Tatras in southern Poland, play a role in the Polish imagination not unlike that of the west and the islands of the Atlantic seaboard in the Irish mind. The Gorals and their region came to exemplify an authentic type of Polishness in which a renewed interest arose during the era of the Young Poland movement of the 1890s and early 1900s, which echoed and coincided with the Irish Revival. Both were manifestations of the forces of cultural nationalism that ran in parallel with political independence movements. Goral combines composition and technique to striking effect as it examines the venerable figure as a kind of ethnographic subject. The figure, in traditional dress, is symbolically located between a church and a wayside shrine, stressing secular and religious traditions.

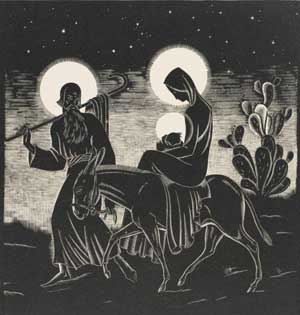

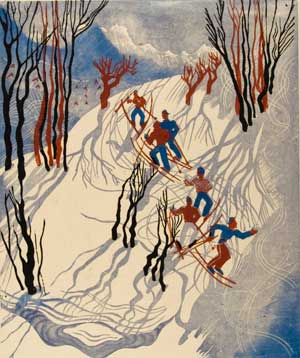

Mother by Tadeusz Kulisiewicz uses a direct composition and stark, graphic style (above). It was informed by long observation, but it was not a study from life. The artist wished to convey a heartfelt representation of ordinary existence and, through the expressive exaggeration of forms, to evoke a way of life. Fleeing to Egypt by Stanisław Ostoja-Chrostowski exemplifies how modern, simplified forms might be employed in a traditional religious subject with no loss of reverence (above). The technique creates a strong, clear image in which the subject is conveyed through monochromatic contrasts, the figures clearly silhouetted with white contours. Among the seven works contributed by Janina Konarska was Skiers, a colour woodcut of a tourist-friendly and fashionable sporting subject of the sort for which she won a silver medal at the art Olympics in Los Angeles in 1932 (above). Other subjects included views of Polish landscapes, towns and cities, as well as scenes of agriculture and cottage industry.

The Dublin exhibition benefited not only from varied examples by leading printmakers but also from a number of specific prints, such as Skoczylas’s Goral, that are now considered to be works of national importance as well as masterpieces of their medium. In sum, the exhibition portrayed Polishness (i.e. Polish ‘national identity’) as Catholic, traditionalist but inventive, coherent but varied, and distinct but not mannered. Such images may have resonated in the Ireland of the 1930s, where the process of (re-)defining post-Independence culture was ongoing.

Through TSPO, the Second Republic sponsored developments that had been in train since the late nineteenth century to encourage the production of art and design that was grounded in Polish traditions and legitimised by historical continuity and inspired by folk art. The Republic sought to compensate for decades of subjugation by affirmative action based on its own aesthetic resources. Modern prints and crafts essentialised Polish aspirations and nationalism.

NO IRISH RECIPROCATION

TOSSPO may be compared loosely with the cultural programmes of the Association Française d’Action Artistique and the British Council in the same period. Ireland did not deploy cultural diplomacy in its approach to nation-building and the development of international connections before the establishment of the Cultural Relations Committee in 1948. Irish diplomacy in the interwar period was directed towards the UK and Commonwealth, the USA, the major states of western Europe, the League of Nations and the Vatican. Ireland did not seek to make links with the newly independent states of central and eastern Europe, nor did it reciprocate the Polish initiative. It may be possible to explain this on the grounds of finance, geography and priorities, but there was no diplomatic imagination on the one hand, and none of the necessary administrative structures on the other. In Ireland and Poland a constructed cultural past was deployed to support modern ambitions. Despite an equally precarious economic situation and at least as great a degree of political instability, the Polish state nevertheless created a successful role for cultural diplomacy.

Gabriela Lojewska is a postgraduate student in the History of Art at Trinity College, Dublin; Philip McEvansoneya is a lecturer in the History of Art at Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

K. Dobrzyńska-Cantwell, An unusual diplomat: Dobrzyński biography (London, 1998).

I. Luba, ‘Art of diplomacy, diplomacy of art during the Second Polish Republic, 1918–1939’, in M. Kuhnke (ed.), Polish diplomacy, art and architecture 1918–1939 (Warsaw, 2017), 5–24.

M. Treter, Polish art: graphic art, textiles (London, 1936), introduction.

D. Wasilewska, ‘International critical reception of propagandist exhibitions of Polish art in the 1920s and 1930s’, Studia Humanistyczne AGH 18 (3) (2019), 45–55.