by Peter Gray

The widespread use of Punch cartoons in books and teaching materials on nineteenth century history is hardly surprising: these often striking images are a convenient visual aid for understanding a period in which photography was in its infancy. Yet the use of this graphic record in an unreflective manner is fraught with difficulties and may detract from the material’s historical usefulness. Several illustrated texts, and at least one academic account of the Great Famine of 1845-50, have been guilty of this unimaginative use of sources, and consequently can be accused of having missed the point of the illustrations. The historical significance of Punch in the later 1840s lay as much in its aspiration and ability to mould public perceptions of events, as in its satiric commentaries on those events. The paper provided no direct record of the mass sufferings of the Irish peasantry (in contrast to the Illustrated London News’ graphic depictions), but Irish affairs occupied many of its pages in the famine years. Perhaps its greatest importance to the historian is as a simultaneous shaper and expression of British public opinion – a phenomenon vital to our understanding of the Famine as a whole.

Considerable political weight

Founded in 1841, Punch sought to establish a new style of humorous journalism, more tasteful and restrained than the savage caricatures of Gillray and Cruikshank, but also more and campaigning than its comic rivals. From the start, it had a moralistic cutting edge, derived from its radical founders, Henry Mayhew and Douglas Jerrold. Even its more conservative contributors believed that humour should be about more than mere laughter. The novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, a regular writer from 1843 to 1854, expressed the view that humour ought ‘to awaken and direct your love, your pity, your kindness; your scorn of untruth, pretension, imposture; your tenderness for the weak, the poor, the oppressed, the unhappy’. This was indeed the mission of the early Punch which led philanthropic assaults on sweated labour, poor law abuses, and terrible urban conditions. The paper’s radicalism was, however, distinctly middle- class in tone; while critical of Chartism, it threw itself whole-heartedly behind the free trade and financial reform movements. Already by the late 1840s, it was beginning a transition to the more complacent conservative stance it would adopt as a patriotic national institution in the mid-Victorian ‘age of equipoise’.

Punch’s political weight was considerable. Its circulation, at around 30,000, was below that of many other journals and was largely concentrated in London, but it reached many metropolitan opinion-formers who set the tone of British middle-class attitudes as expressed nationally. It was read by politicians, and several cabinet ministers commented on its pronouncements in their private diaries. Most importantly, Punch existed as part of a network of similarly- oriented journals. Its authors were keen to take their line on public affairs largely from The Times, by far the most influential newspaper of the day. Indeed one contributor, Gilbert a Beckett, was simultaneously a leader writer for both The Times and The Illustrated London News. The power of these three papers taken together was considerable – each complemented the other by focusing on a different aspect of middle-class taste. This was all the more true in a period of party flux, weak governments, and a national radical middle-class mobilisation.

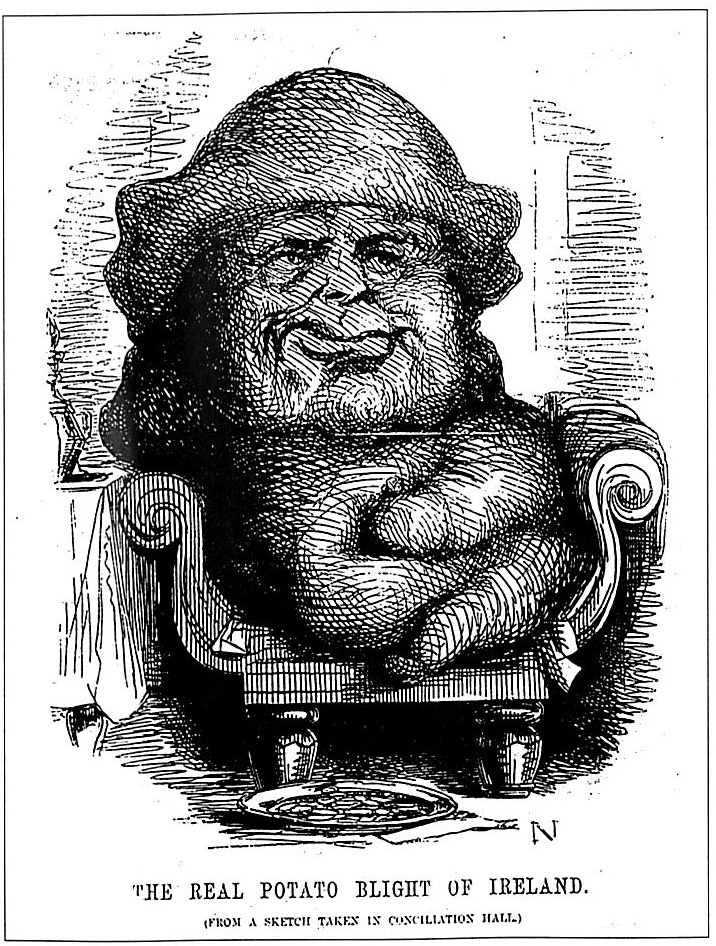

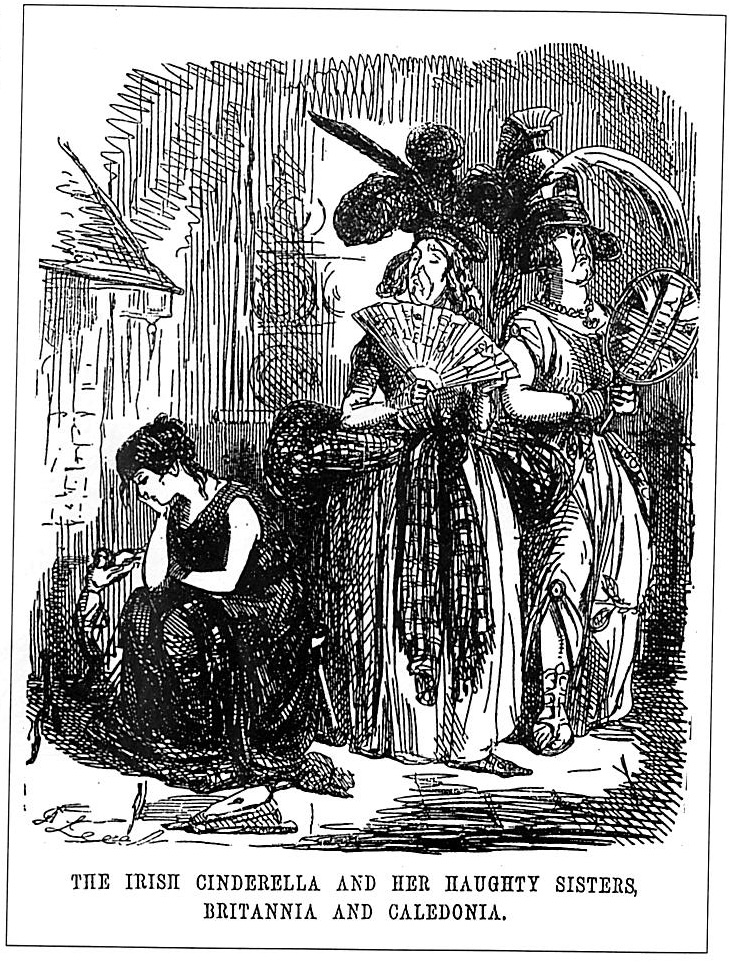

Punch had a history of broad sympathy for the plight of Ireland, mixed with a mocking hostility towards Daniel O’Connell and the Repeal movement. In the early stages of the famine catastrophe, O’Connell was attacked for his alleged greed in collecting the ‘Repeal rent’ from the starving poor and for misleading his ignorant followers as to their real interests. [The Real Potato Blight of Ireland, 13 December 1845] Attention was thus directed away from the realties of the socio-economic crisis, to what were regarded in Britain as the ludicrous and seditious political antics of the Irish. Political and moral factors were to be relentlessly harped upon in the subsequent years as the true causes of Irish distress. While ‘Hibernia’ could be treated sympathetically as a feminised abstract, and her ‘Haughty Sisters, Britannia and Caledonia’ upbraided for their self-satisfied aloofness [The Irish Cinderella, 25 April 1846], Punch regarded the Famine more as an opportunity to ‘conquer’ Ireland ‘by food and education’, than as a case for simple charity. The excessive luxuries of the rich in Britain were a target more conducive to radical (and indeed evangelical) criticism than an inadequate relief policy.

Providence and the potato

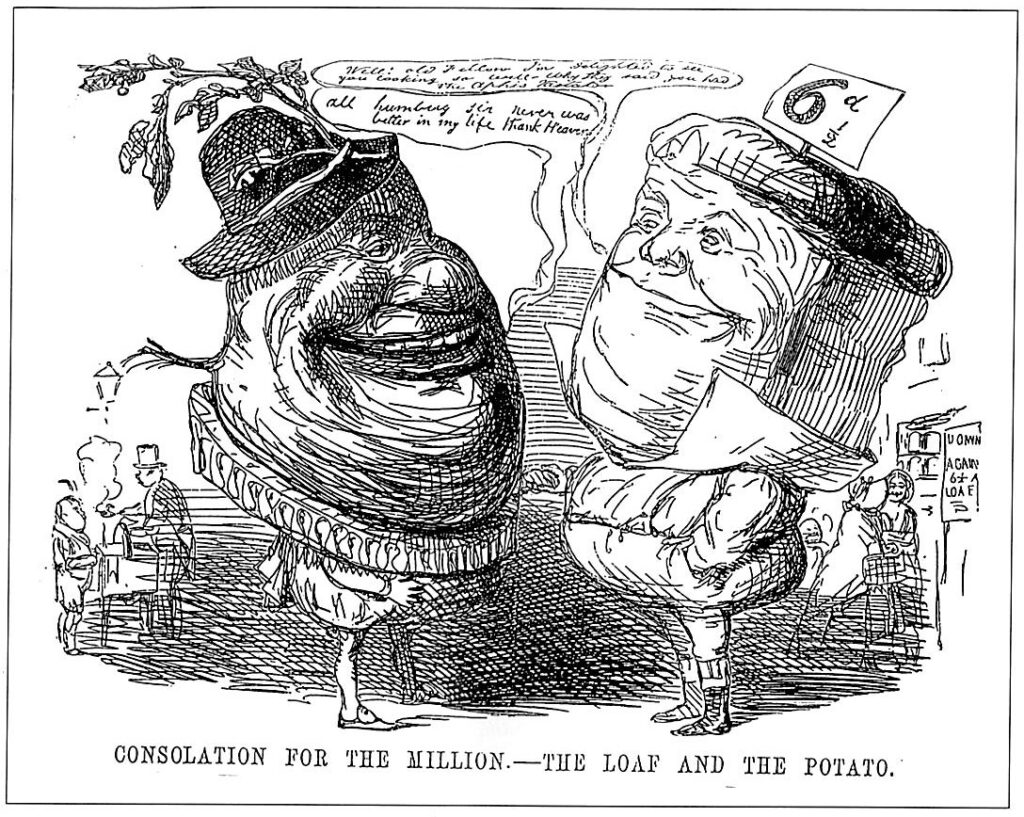

The paper mocked the antiCatholic interpretations of famine causation proposed by ultraProtestants, but it did not rule out the hand of God. Indeed it implicitly gave credence to those providentialist views which saw the potato blight as a means of replacing ‘backward’ potatoes (and the social system their cultivation supported) with more ‘civilised’ foodstuffs. It agreed with The Times that ‘Providence, which made us and the land we till, evidently intended another subsistence’ than the potato, that ‘most precarious of crops and meanest of foods’. Ministers agreed that the introduction of cheap imported grain would transform the Irish character. Edward Cardwell argued:

If, while they diffused among [the Irish] a taste for a higher kind of food, they could also introduce amongst them habits of industry and improvement calculated to furnish them with the means of procuring that higher food, they would be effecting one of the greatest practical improvements which this country was capable of accomplishing.

This policy necessitated a strict adherence to free trade in food and bound up Ireland’s fate with the repeal of the corn laws. From autumn 1846, British governments adopted a bi-partisan policy of minimal interference in the food trade. The collapse in the price of imported Indian meal the following summer appeared to vindicate this free trade dogma, but this was of little consolation to the hundreds of thousands who perished in the winter of 1846-7. The social costs of that year blunted but did not change the moralistic British critique of potato subsistence; Punch prematurely welcomed the apparent restoration of the potato to health in autumn 1847 (it failed again in 1848 and 1849), but only as a subsidiary to cheap bread. [Consolation for the Million: The Loaf and the Potato, 11 September 1847] Like Sir Charles Trevelyan, the assistant Secretary to the Treasury, Punch regarded the continuation of famine conditions in Ireland after this time as entirely due to indigenous moral and not biological failures. Ireland had been warned of the folly of potato dependence by a ‘natural’ disaster, but had perversely chosen to ignore the danger; no further responsibility could be undertaken by the ‘imperial’ government.

Irish property, Irish poverty

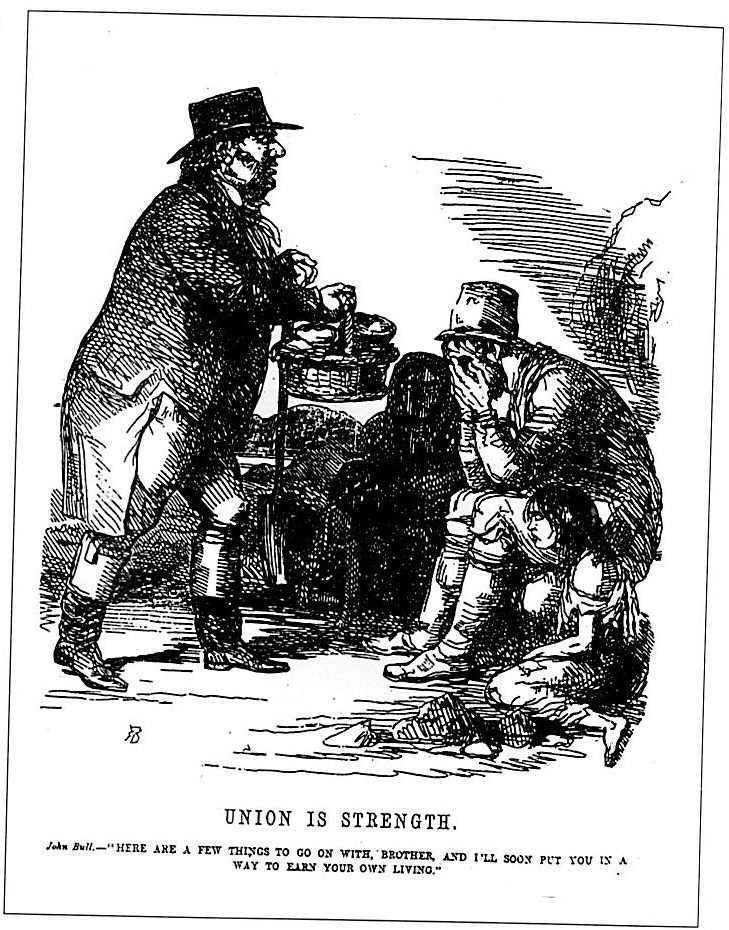

The relief of famine distress was bound up with ideological considerations. In the cartoon Union is Strength (17 October 1846), John Bull, the epitome of Englishness, presents his Irish ‘brother’ not only with food, but with a spade – to put him ‘in a way to earn your own living’. In the light of modern conceptions of the importance of development aid, the offer appears sensible but it must be understood in the light of the popularised versions of political economy current at the time. Thomas Campbell Foster’s analysis of the ‘Condition of the People of Ireland’, serialised by The Times in 1845-6, had stressed the essential fertility of Ireland and placed the blame for its backwardness on ignorance and a lack of enterprise. The idea that wealth could be created by industrious exertion alone (capital being merely ‘accumulated labour’) acquired considerable popularity. There was also a widespread belief, shared by some ministers, that Ireland possessed sufficient surplus in its ‘wages-fund’ to support its current population, if only this was diverted from landlord extravagance to productive use. While Punch acknowledged that the scale of the 1846-7 crisis necessitated some assistance, and rejected the crude Malthusianism of Lord Radnor, this feeling continued to lie at the root of its perceptions. With The Times, it advocated the early introduction of a permanent extended Irish poor law, which would make Irish property support Irish poverty. This ‘very bitter pill’, strictly administered as a moral spur to self-reliance on the part of all Irish classes, proved popular in Britain. By May 1847 Punch, was advocating total reliance on the government’s new poor law and leaving Ireland to ‘shift for herself for a year’.

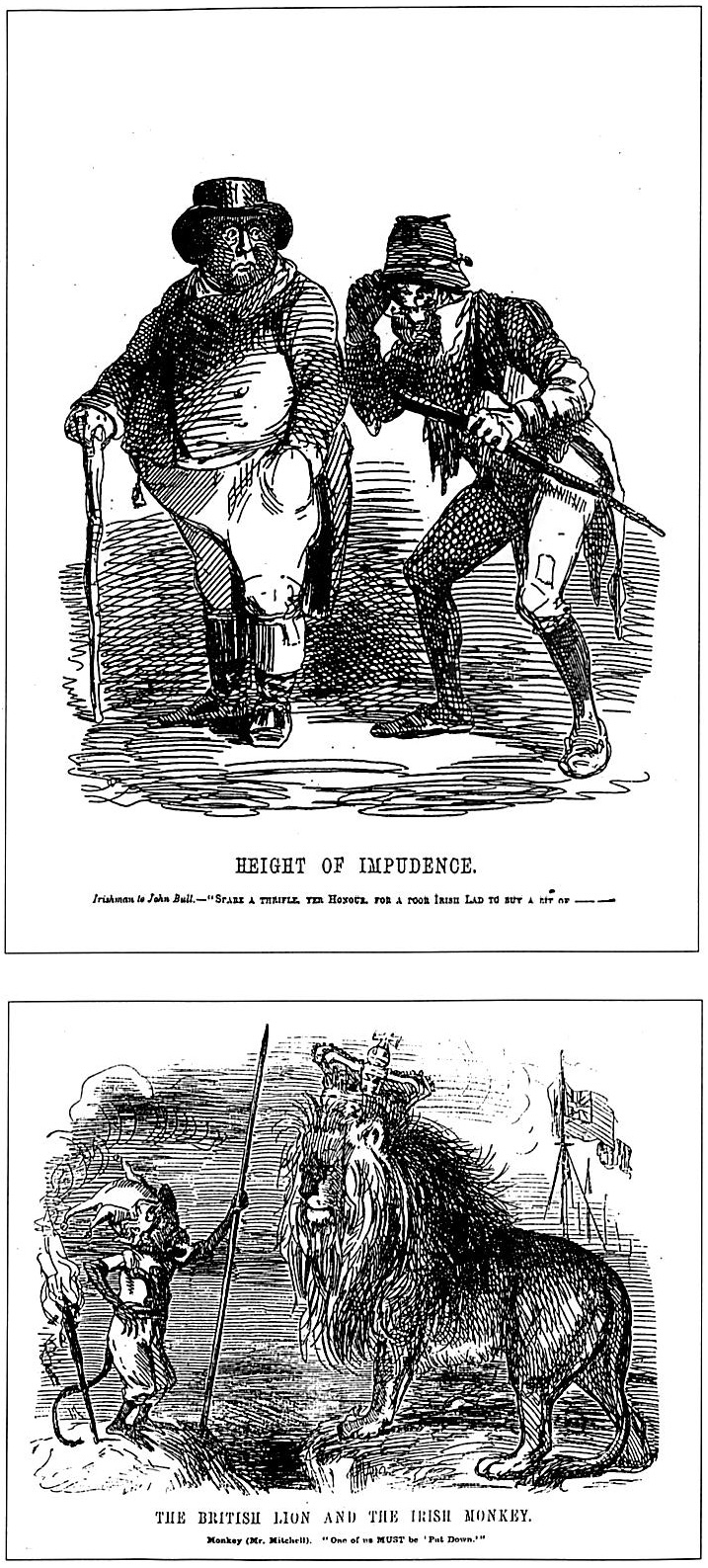

Two developments were cited for hardening Punch’s (and by extension, British public opinion’s) heart against Ireland. Both centred on the theme of Irish ‘ingratitude’. Within two months of ‘Union is Strength’, Punch had decided that the Irish were rejecting the proffered spade and relapsing into atavistic violence. In Height of Impudence (12 December 1846), John Bull is accosted by an Irishman begging alms to buy a ‘blunderbuss’. In contrast to the earlier cartoon, the Irishman is no longer ‘brother’, but bears the simianised features that were to become so familiar to Punch’s readers in later years. To some extent this shift reflected the views of the individual cartoonists; ‘Union is Strength’ was drawn by Richard Doyle, a Catholic and of Irish descent (although as strongly anti-Repeal as his father, John Doyle of Political Sketches fame). ‘Height of Impudence’ was by John Leech, Punch’s regular cartoonist in these years, and a man whose betes noires featured ‘Italian organ-grinders, Frenchmen and Hebrews’ as well as the Irish. The anthropological theories of ‘Celtic’ degeneracy which informed such stereotypes of ‘Paddy’ were by no means universally accepted in 1840s Britain, but were mobilised forcefully for specific purposes in Punch and The Times. This transition period between the dominance of environmentalism and racialism as the leading discourse regarding Ireland was particularly disadvantageous to the country: while brute enough to require coercion, the Irish were seen as sufficiently ‘normal’ to be expected to exhibit self-reliance, and were denied the paternalistic relief later doled out by Dublin Castle in the subsistence crises of the 1880s and 1890s.

Punch came to support strict coercion of Ireland, the suppression of agrarian agitation, and the imprisonment of troublesome priests. Yet in line with its radical leanings, it expressed little sympathy for Irish landlords, who were depicted as ready to rob John Bull to line their own pockets and subsidise a lifestyle of cowardly absenteeism. The paper showed no sympathy for the developing campaign for tenant right, but – in the wake of The Times – moved towards advocating more drastic treatment of the Irish of all classes.

Mitchel as a monkey

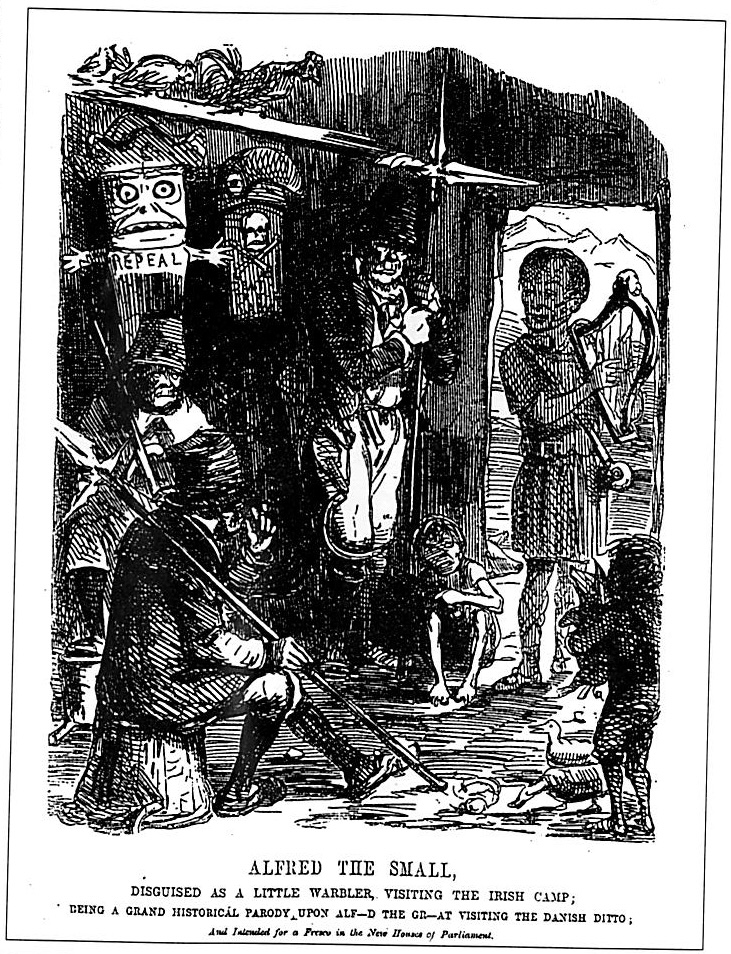

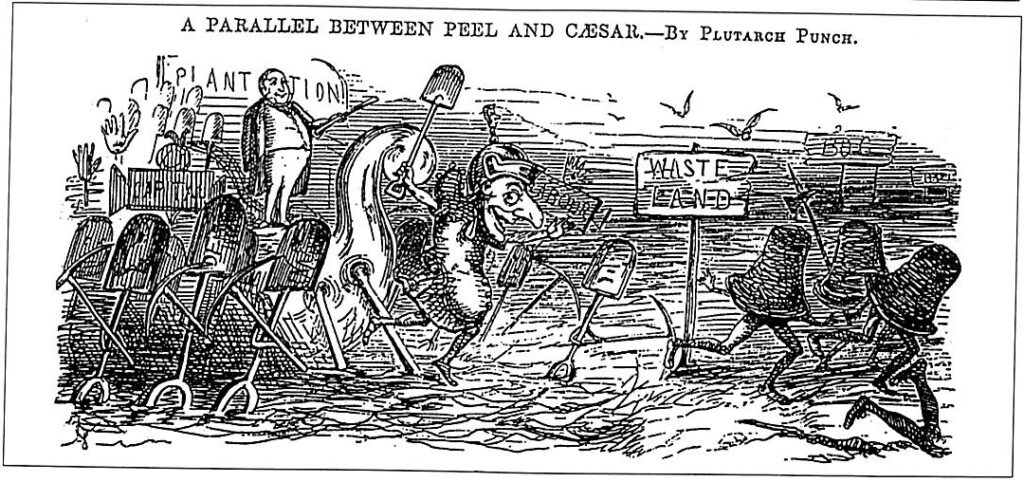

The second development increasing British antagonism was the growing political instability of Ireland. ‘Union is Strength’ had suggested an optimistic outlook on Anglo-Irish relations, and Punch had gloated at Daniel O’Connell’s apparent renunciation of Repeal and request for greater British aid shortly before his death in 1847. In this context, the increasingly vociferous militancy of the Young Irelanders provoked outrage and a further denunciation of the Irish as a whole. Leech went the full way with the simian stereotype by portraying the movement’s most extreme leader, John Mitchel, as a monkey – at once comic and dangerously incendiary – threatening a magisterial and contemptuous British lion. [The British Lion and the Irish Monkey, 8 April 1848] In the wake of the abortive 1848 rising, Punch returned repeatedly to the theme of inveterate Irish barbarity and ingratitude. Agrarian unrest and political rebellion were rolled together (in a manner which Fintan Lalor and Mitchel would have envied had they been so in reality), and images of famine-related suffering were ignored. British policy appeared incapable of ameliorating the situation through conciliation. In Alfred the Small (16 September 1848), the Prime Minister, Lord John Russell, is pictured visiting Ireland, only to find the primitive natives immersed in violence and idolatrously worshipping the totems of Repeal.

Thackeray: Hibernis Hibernior

If Punch ‘s main political thrust lay in its chief cartoon – the subject of which was decided weekly by the principal contributors – the paper was always more than its ‘big cut’. It carried numerous one-liners, squibs and articles on Irish subjects, as well as pieces of more sustained satire in verse and prose. W.M. Thackeray was the source of the bulk of its Irish pieces in these years. His Irish Sketch Book (1843), an impressionistic but largely critical account of an Irish visit, had proved a great success in England (not least for its strident anti-Catholicism). It was on the strength of this that he emerged as Punch’s Irish expert, often under the pseudonym ‘Hibernis Hibernior’, In ‘Mr Punch for Repeal’ (26 February 1848) Thackeray declared that he had made a personal contribution of £5 to the British Association relief fund in early 1847, but as reasons for giving no more, went on to cite the support of certain Catholic clerics for the tenant movement (which Thackeray interpreted as a murderous conspiracy), and John O’Connell’s criticism of the British state and press for failing to come to terms with the continuation of the famine. This clearly echoed the mood of British public opinion, for a second charitable appeal in October 1847 had proved an unpopular flop and no further substantial sums were raised. Thackeray also took up the cry for ‘Repeal’ in an ironic sense, as a means of protecting England from further Irish mendicancy. These themes were reiterated in the ‘Letters to a nobleman visiting Ireland’ (2 and 9 September 1848), in which Lord John Russell was upbraided for his previous political connections with the O’Connells, and Irish poverty was attributed to Irish wrong-headedness.

Manipulating British public opinion

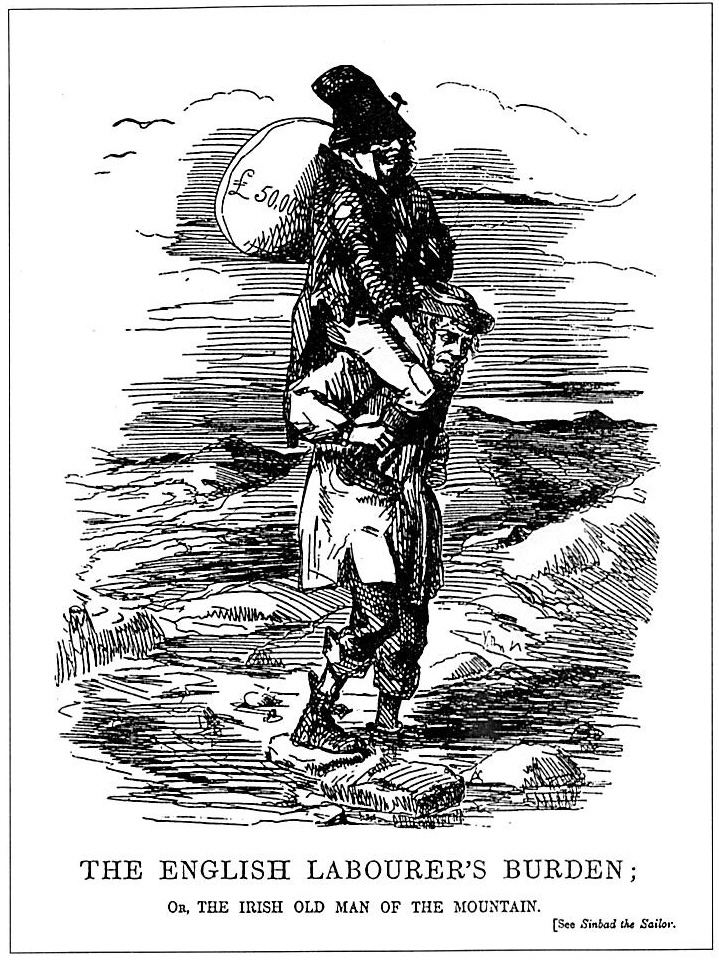

Punch regularly criticised Russell for having no Irish policy, but also staunchly opposed government expenditure in Ireland. In the wake of the financial crisis of autumn 1847, British industry and commerce underwent a period of depression: middle-class radicals responded by crusading against taxation and landlord privileges. The general election of 1847 gave a group of about 85 radicals, led by Cobden, Bright and Hume, the parliamentary balance of power. Both Russell and Lord Lieutenant Clarendon were aware of the vital need for increased relief, development and emigration assistance spending in Ireland but they failed to make headway, faced with ideological hostility from the advocates of ‘natural causes’ within the government and strenuous resistance from the commons. Punch expressed glee when Russell was forced to withdraw a proposed increase in the British income tax in his 1848 budget, and then outrage at every concession extracted to meet the extensive distress of the west of Ireland in 1848-9. Every loan to the ungrateful Irish, however small, was denounced as an additional burden on England’s respectable poor. [The English Labourer’s Burden, 24 February 1849] It was indicative of just how deeply divided the Whig-liberal cabinet was that such irresponsible press statements were welcomed and encouraged by some ministers. From late 1846 Charles Wood, Chancellor of the Exchequer, sought to undermine relief expenditure by stimulating a British backlash against the ‘monstrous machine’ of public works. He, Trevelyan and Colonial Secretary Lord Grey had close connections with Delane of The Times and exploited these for political ends.By autumn 1848, a broad swathe of British opinion was convinced that mass starvation was inevitable in Ireland, and should not be prevented. The diarist Charles Greville noted that the prevailing sense in London was ‘disgust … at the state of Ireland and the incurable madness of the people’. The press had done much to create this perception. The Prime Minister was obliged to admit that it was less the ‘crude Trevelyanism’ of his subordinates than feelings lying ‘deep in the breasts of the British people’ that had made substantive intervention impossible.

‘Biped livestock’

As if exhausted or secretly embarrassed by its sustained hostility during a period of acute suffering and mass mortality, Punch sought for signs of hope in 1849. Two events were. The ‘new plantation’ scheme proposed by elder statesman Sir Robert Peel was warmly welcomed. Peel suggested a commission with sweeping powers over the west of Ireland that would pave the way for ‘new proprietors who shall take possession of the land of Ireland, freed from its present encumbrances, and enter into its cultivation with adequate capital, with new feelings, and inspired by new hopes’. Richard Doyle pictured Peel as ‘The New St Patrick’, driving the reptiles of ‘destitution’, ‘mortgages’ (depicted by a Jewish stereotype) and ‘famine’ out of Ireland. Leech welcomed Peel’s ‘panacea’ of ‘the sale of encumbered estates’ as the cure to Russell’s ‘dreadful Irish toothache’. The idea of a British economic ‘colonisation’, reclaiming the bogs of Connacht for civilisation, appealed strongly to the paper, and a mass removal of the ‘biped livestock’ by clearance and emigration was welcomed. [A Parallel between Peel and Caesar, 28 April 1849J Yet, like The Times, its support was primarily for ‘free trade in land’ rather than full-scale government intervention. Peel had advocated relaxation of the poor law and increased state investment, but moralist opinion remained adamantly opposed.

The second event was the Queen’s visit to Ireland in August 1849. The unifying mystique of the monarchy was sufficient for Punch to restore the image of a poor but welcoming ‘Hibernia’, and to transform the threatening ‘Paddy’ into the comically harmless ‘Sir Patrick Raleigh’. [Landing of Queen Victoria in Ireland, August 1849] Punch put its faith in the royal visit as the most efficacious mode of anglicising the country and its people, imagining an Ireland of the future built on the suppression of its past:

Let Erin look forward with faith sublime, Forgetting the days that are over; And allow the stream of a brighter time In oblivion the past to cover.

[Ireland – a Dream of the Future, Sept. 1849]

This was wishful thinking, and the flood of private and corporate investment expected in the wake of the Queen’s visit failed to materialise. Plans by the City of London corporation to purchase large tracts of Connacht also fell through.

Conclusion

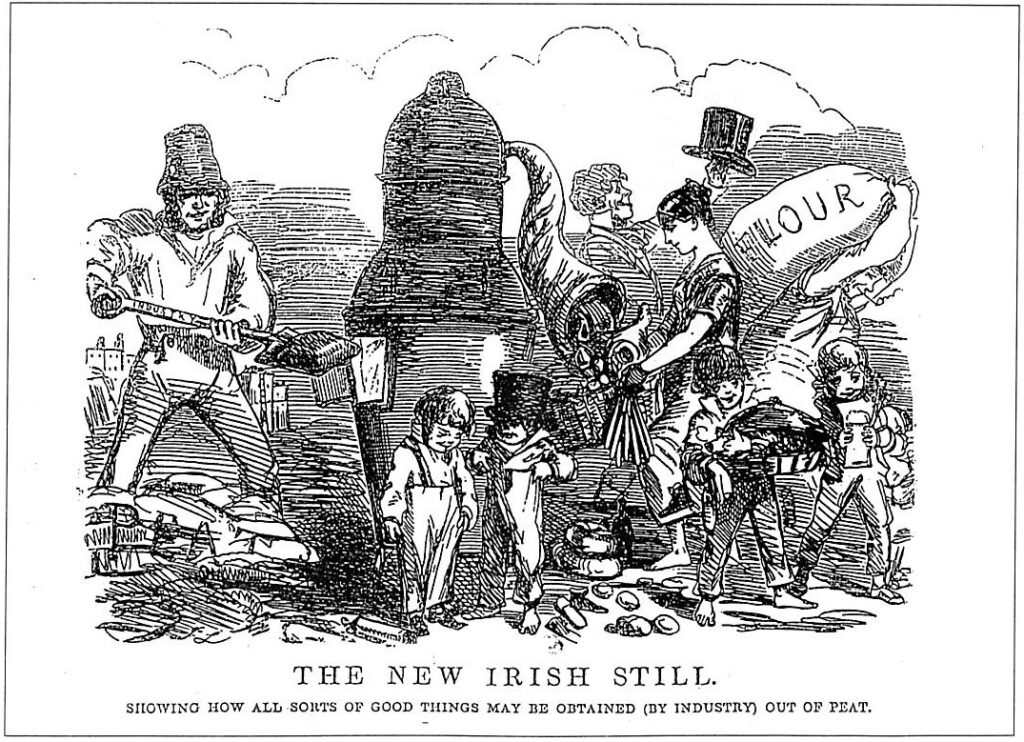

Punch’s vision of Irish prosperity arising simply from self-exertion – ‘new’ proprietors were primarily to provide entrepreneurial values rather than cash – proved illusory. Yet such was the depth of early Victorian liberal optimism that it refused to abandon the image of creating plenty through the application of industry to peat. [The New Irish Still, August 1849] The idea would be ludicrous, were it not for the fact that this illusion, and the moralistic outrage directed against the Irish when it was not realised, underlay the response not only of Punch, but of the dominant strand of British public opinion, to the Great Famine. The specific political circumstances of the later 1840s entailed that this opinion played a considerable part in limiting the options available to a weak and deeply divided government. The present debate amongst historians over whether and where moral responsibility for the famine can be attributed would be illuminated if such aspects were sufficiently taken into account.

Too detailed an analysis can perhaps detract from the wit and humour of nineteenth-century cartoons and comic writing. Yet these were not merely intended as amusing frivolities. They had real political significance and should be treated as historical documents. We should beware of too hastily passing judgement on the people of the past but surely the performance of Punch can be evaluated in the light of its own critique of O’Connell in 1845:

A joke is a joke, and nothing can be more pleasing … in its proper place – but not always. You wouldn’t cut capers over a dead body, or be particularly boisterous and facetious in a chapel or a sick-room; and I think, of late … you have been allowing your humour to get the better of you on occasions almost as solemn. For, isn’t Hunger sacred? Isn’t Starvation solemn?

When applied to Ireland, the answer appeared to be that it was not.

Peter Gray tutors in Irish history at Queen’s University, Belfast.

Further reading:

L. Perry Curtis, Apes and Angels: the Irishman in Victorian Caricature (London 1971).

S. and A. Briggs (eds.), Cap and Bell: Punch’s Chronicle of English History in the Making 1841-1861 (London 1972).

M.H. Spielmann, The History of Punch (London 1895).

C. Woodham-Smith, The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845-9 (London 1962).