By John Martin

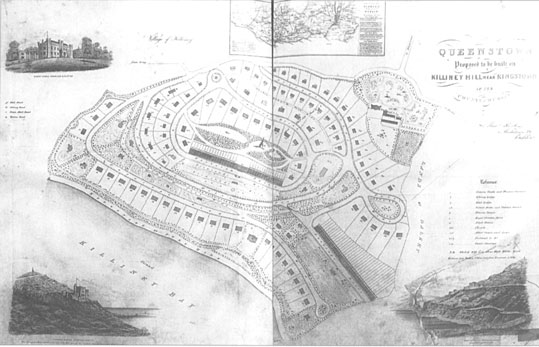

Many visitors to Killiney Hill Park stop at the viewing point just below the obelisk to enjoy the superb panorama over Killiney Bay and the Dublin/Wicklow mountains. Most of them would be surprised to learn that the wooded hillside sloping down to the Vico Road was the site in 1840–1 of a proposed ‘new town’, to be called Queenstown in honour of the young Victoria. Had it proceeded, the landscape would have been radically different, as shown on Haverty’s drawing based on the architect’s plans. Over 180 detached and terraced houses, together with two hotels and a mineral water spa, would have lined the hillside. What was this ambitious project? Who were its promoters? And why did it fail?

The story begins in 1834 when Robert Warren, a wealthy solicitor, bought the 155-acre Mount Malpas estate on Killiney Hill for £7,000. It had been laid out as a deer-park in the late eighteenth century by Lord ‘Copper-faced Jack’ Clonmel. Within a few years Warren had not only refurbished Killiney Castle on the west side of the hill but also built several substantial dwellings, such as Victoria (now Ayesha) Castle and Mount Eagle overlooking Killiney Bay on the east side. Both were clad in granite, as was the archway at the entrance to the private road at Killiney village. The Coburg (now Vico) Road remained closed to the public until 1889, when it was opened officially by the lord lieutenant.

In the late 1830s Warren was approached by Valentine Hosking, an architect, engineer and surveyor about whom little is known other than that his previous addresses included Liverpool and the Isle of Man. While it was Hosking who conceived the Queenstown project, Warren became an enthusiastic supporter, perhaps viewing it as an ambitious extension of his own recent developments. Moreover, following an analysis by Professor John Apjohn, a Dublin scientist with an established reputation, a spring on the Killiney lands was found to be rich in iron salts. Apjohn concluded that the composition of the spring water was like that found at the famous spa town of Tunbridge Wells in Kent, encouraging Warren to believe that the establishment of a spa at Killiney would attract English visitors.

QUEENSTOWN JOINT STOCK BUILDING COMPANY

The likely scale of investment required exceeded even Warren’s resources, and at a meeting held in Dublin in September 1840 to attract investors both he and Hosking set out their proposal, illustrated with plans and sketches. Apjohn’s chemical analysis was also tabled. Two prominent Dublin personalities—Martin Burke, founder of the Shelbourne Hotel, and Dr Richard McDonnell, fellow (and later provost) of Trinity College, Dublin—spoke warmly in favour of the proposed new town. Both were involved in housing development on former squatters’ land between the Sorrento and Coliemore Roads in nearby Dalkey; McDonnell’s son, Hercules, was soon to instigate the building of Sorrento Terrace, which also enjoys a spectacular coastal setting. The meeting agreed that a provisional committee should create a joint stock building company to progress the Queenstown project, a key element of which would be ‘a first-rate watering place’. The membership of the committee included the lord mayor of Dublin and Martin Burke. Warren offered to sell the 120-acre site to the company, or to lease it for 900 years.

The proposed Queenstown Joint Stock Building Company published a detailed prospectus in the Dublin newspapers on 12 June 1841:

‘The want of a first-rate watering place in the vicinity of the metropolis has long been the surprise of visitors, while so many towns of a similar description have been established within a few years in England and other countries, on sites very inferior to the one selected for Queenstown, and with great profit to the shareholders. It is presumed, from want of such an establishment, and the very high rent obtained for building ground and houses in the vicinity … that a very large profit will accrue to the shareholders in the purchase of the estate, the formation of roads and pleasure grounds, the selling or leasing the frontage for building, and in carrying out the whole design, or part thereof, by a building company.’

PROSPECTUS

Fifteen thousand shares of £10 were offered. Warren agreed to sell the land for £35,000 and pledged to invest £10,000 of that sum in shares. Plans drawn up by Hosking envisaged 103 marine villas, cottages ornées and rural houses, 80 terraces and crescent houses, and two hotels, together with public baths with pump room for the water of the mineral spring, temples, grottos and embellishments, as more fully set out in the architect’s report which accompanied the prospectus. Over three miles of roads were proposed, including Coburg Road, part of which had already been constructed to serve the dwellings previously built by Warren. The names of the new roads—Victoria Road, Albert Road and the Royal Crescent—no doubt reflected his political loyalty but may also have been designed to appeal to a British audience; the share list was opened in London as well as Dublin. The frontages of housing sites varied from 110ft to 25ft, to accommodate a range of dwelling types and sizes. There were to be four miles of footpaths and various pleasure grounds. The plans of the new town could be inspected at the company’s office in Dame Street and a solicitor’s office in Bloomsbury Square, London.

Costings prepared by engineers were presented, amounting in total to £140,000. Apart from the site purchase cost of £35,000, the main items included £51,000 for building 26 terraced houses and eight villas at £1,500 each (the remainder would be build by other purchasers), £20,000 for constructing roads, and £19,000 for waterworks for the town and other contingencies. The prospectus pointed out that Warren was earning over £400 in annual rent from the three houses already built and incorporated in the overall layout. Persons holding 100 shares would be qualified to be elected directors and able to choose their own sites for building (in accordance with the plans) should they so wish.

DIFFICULTIES

The project soon ran into serious difficulties and proved a complete failure. Shortly before the prospectus was published, a meeting of the provisional committee resolved that, although the share list would be opened, no one putting his name down for shares would be liable to pay anything until a bona fide joint stock building company had been formed. Only when the sum of £70,000 in shares had been subscribed would a general meeting of the shareholders be convened for the purpose of forming such a company. The putative company employed Hosking for six months, at £6 per week, to carry out the design work, but at the end of the period the architect demanded more money before he would hand over his plans and maps. Hosking was declared insolvent, and his discharge at the debtors’ court in February 1842 was opposed by Warren, who had actually paid his fees. At the hearing, the company secretary acknowledged that the company had subsequently ceased to exist and that no money from the public had been received by them. Hosking was discharged by the court when he agreed to hand in his plans etc. for the benefit of his creditors. His Dublin office appears to have been closed and he disappeared from the scene.

Several reasons can be put forward for the collapse of the Queenstown project. First, it clearly failed to win support from prospective investors, either in Dublin or London. The relatively limited pool of wealthy Irish people in post-Union Dublin had a range of other investment options, including railway companies; the Dublin and Kingstown Railway Company, for example, was already planning an extension of the route from Kingstown to Dalkey, and onwards to Bray and Wicklow, the line of which would be laid between Vico Road and the sea through Warren’s land in 1854, including a station at the bottom of Obelisk Hill (until 1858).

Second, even had sufficient capital funding been forthcoming in 1841, it is highly unlikely that it would have been possible to build the number and size of buildings proposed on such steeply sloping ground; the shading on the first-edition Ordnance Survey map of Killiney Hill in 1843 illustrates the nature of the problem. Although the prospectus tried to reassure potential investors by quoting estimates of relatively modest gradients on the proposed new housing roads, these figures related to the horizontal sections, i.e. broadly parallel to the contour lines; no details of cross-sections measuring the downhill slope were provided.

Third, it was customary at that time for houses to rely on wells and pumps; the public water-supply from the Vartry reservoir only became available around 1870, and even then special arrangements had to be made to supply houses on higher ground on Dalkey Hill. It is not known how the proposed expenditure of £19,000 for waterworks etc. could have provided a supply for a population in the order of 1,000 people (including the hotels). Similarly, no details of proposed sewerage were given; a private company would have lacked the statutory powers granted to sanitary authorities in the 1870s, and the Killiney and Ballybrack township was not established until 1866. Furthermore, although Apjohn’s analysis confirmed the quality of the mineral water spring on Killiney Hill, the average flow of water was not stated, so it is unclear whether it would have been sufficient to sustain a commercial spa on the lines of Tunbridge Wells.

Surprisingly, given the failure of the project, Warren seems to have retained some lingering hope that it might be resurrected. He published the following advertisement in 1845:

‘To be let, Victoria Castle, Albert Castle, Kent Lodge etc. … varied private enclosed pleasure grounds of great extent (on which Queenstown is proposed to be built) … The proprietor of this rising and very valuable property, on which there are numerous splendid building sites, would sell the entire thereof, with all the buildings and improvements thereon. There is a very superior chalybeate [rich in iron salts] spring on the hill, the medical virtues of which are equal to the celebrated spa at Tunbridge Wells.’

It was not to be. Warren engaged in various other speculative developments in south County Dublin that proved to be unwise, and after his death in 1869 his lands at Killiney were sold in the Landed Estates Court. Killiney Hill Park was purchased by the Queen Victoria Memorial Association from Robert Warren Jr for £5,000 and was opened as a public park by Prince Albert in 1887. Today anyone can enjoy the views from Obelisk Hill, which had once been intended for wealthy investors in the new town of Queenstown.

John Martin is the author of Irish Historic Towns Atlas no. 30: Dungarvan (Royal Irish Academy, 2020).

Further reading

P. Pearson, Between the mountains and the sea: Dun Laoghaire–Rathdown County (Dublin, 1998).

See https://killineyhistory.ie/the-killiney-castle-estate-of-robert-warren-1834-1869/.