PLATON MIKHAILOVICH KERZHENTSEV, THE FIRST SOVIET HISTORIAN OF IRELAND

By Maurice J. Casey

In 1914 the Irish poet Padraic Colum and his wife Mary arrived in New York. Initially, they expected to remain for a few months. World events, however, compelled alternative plans, as the descent of Europe into war quickly riveted them to their new surroundings. Daunted yet determined, the Colums found lodgings, run by an eccentric patron, Monsieur Froissard, alongside other emigrés in a similar state of stasis. Living in the building with their young son were the Lebedevs, a Russian couple remembered fondly in Mary Colum’s memoir. The Lebedevs were veteran revolutionaries and reminisced about their joint incarceration following the 1905 revolution. Fearing that their radical past would be uncovered by less discreet company, the Lebedevs informed their Irish friends in hushed tones that they still belonged to the clandestine world of Russian radicals. Remarkably, from this cohabitation of an Irish and Russian couple, both of which had connections to the ongoing struggles at home, grew the first Soviet scholarship on Ireland.

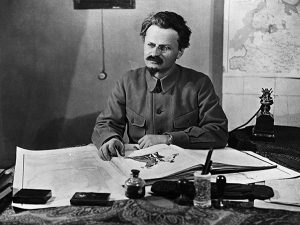

Dinner with Trotsky

Lodgers at Monsieur Froissard’s boarding house had the privilege of inviting a guest to dinner, provided they informed their patron in advance. Occasionally the Lebedevs would invite a bespectacled friend who worked for an East Side Jewish newspaper, informing the Colums seated beside them that he, like them, was a revolutionary. Mary recalled the ‘bright, intent little man’ who brought London left-wing periodicals to the boarding house. This Mr Bronstein, she noted, became ‘of all things’ the head of an army. Bronstein, of course, was Leon Trotsky. Though certainly less influential than his dinner guest, Platon Lebedev, better known as Platon Mikhailovich Kerzhentsev, became a figure of history in his own right. An experimental Soviet playwright, he later made his mark as a prominent Bolshevik cultural official and the first Soviet historian of Ireland. As the cultured émigrés of two countries shared accommodation and dinners, neither was aware of the coming events in Ireland that would soon draw their worlds even closer together.

In Easter 1916 the Irish republican insurrection in Dublin was fretfully organised and subsequently repressed. By now the Colums had settled into their American surroundings. Padraic embedded himself within the bohemian circles of New York, sporadically contributing poems to Emma Goldman’s anarchist journal, Mother Earth. The news of resistance in Dublin reached the boarding house to a mixed reaction. French lodgers denounced the rebels as reckless. The Russians, however, were more sympathetic. With their former acquaintances attempting a radical transformation of Ireland, the Colums contemplated returning. Platon, keenly interested in the events, offered financial assistance for their journey home. Leaving the boarding house marked the last they saw of the Lebedevs. Nonetheless, Platon’s brief life amongst the literary couple proved only the beginning of his relationship with Ireland.

Bolshevik interest in Ireland

In the aftermath of the Rising, new publications arose and dissipated in Dublin, eroded by the tide of censorship and financial constraints. Behind a number of these periodicals were two features of the Dublin cultural landscape, L.P. Byrne and Patrick Little. The duo worked for various left-leaning journals as the Irish revolution set itself apace. A theatre critic with links to the co-operative movement, Byrne maintained connections with the world of Russian revolutionaries living in London. Through these networks Byrne liaised with a small group of Bolsheviks interested in visiting Dublin. This Irish–Russian radical encounter was later recalled by Little when he was brought before the Bureau of Military History to recount his experiences of the Irish revolution. Four Russian revolutionaries arrived to a Dublin still strewn with rubble, each travelling under a pseudonym to avoid detection. Amongst their number was the later Soviet ambassador to Britain Ivan Maisky, travelling under the name ‘Likaevsky’, and Platon Lebedev, who had adopted a moniker befitting his radical trajectory: Kerzhentsev. Their aims were twofold: to analyse the street-fighting tactics of the rebels, and to study the theory of Ireland’s pre-eminent socialist theorist, James Connolly. With their own revolution fast approaching, the Bolsheviks kept their trip short and arrived back in London to await signals for a return home.

The brief visit was not without consequence. Tsar Nicholas II abdicated in March 1917, propelling the provisional government into power in Russia. The call pulsed outwards from Russia for her exiled revolutionaries to head homeward and take part in the shaping of a new society. Consequently, Lenin’s vanguard party arrived at the helm of the former Russian Empire, navigating a sixth of the earth’s territory towards a socialist future. Platon, triumphantly returned to his country, was now thrust into organising the Soviet press. Mining world events for propaganda gold, he naturally drew on his own experience. In 1918 he authored the first Soviet history of revolutionary Ireland, Revolutsiayannaya Irlandiya. Liberally citing James Connolly, Platon chose an unusual sobriquet for the events of Easter 1916. The republican insurrection was labeled Krasnaya Pashka, Red Easter.

Russia quickly descended into civil war, a situation worsened for the Bolsheviks by the arrival of Allied troops supporting the White Russian opposition. In 1921 the intrepid Irish soldier Francis McCullagh landed in Omsk with the British forces. When his position was compromised, the Red Army imprisoned McCullagh. Using a fluency in Russian he had acquired from an earlier adventure amongst Cossack troops, McCullagh deftly negotiated his way out of captivity. Free to navigate the birth of Russia’s new order, he found himself inside a Bolshevik propaganda hall face to face with ‘Comrade Kerzhentsev’, a man he termed ‘the Bolshevik expert on Irish affairs’. The Bolshevik impressed upon McCullagh his knowledge of Irish history and referenced his brief visit to Dublin. To McCullagh’s eyes, Platon’s team of propagandists seemed to be making ample use of the upheaval in Ireland. This remarkable encounter is preserved in McCullagh’s travelogue of his experiences. The soldier continued his journey, leaving Comrade Kerzhentsev to continue deploying Ireland as a model of imperialism’s iniquities.

Continued interest in Ireland

Platon continued his interest in Ireland beyond the days of its clear propaganda utility. In 1936 an illustrated edition of his early work on Irish history was published. The book contained a new rendition of his earlier section on the Irish cultural revival. In a tribute to the poet with whom he had once lived, Platon placed Padraic Colum alongside other towering figures of Irish letters such as Yeats and Russell. Platon was himself a fixture of the Soviet cultural apparatus, mixing with figures such as Dmitri Shostakovich, Maxim Gorky and Mikhail Bulgakov.

The publishing of Platon’s work in English provided another connection between this Soviet writer and Ireland. In 1937 his Life of Lenin was published in a number of languages by a Moscow printing press devoted to disseminating Soviet literature abroad. Margaret ‘Daisy’ McMackin was given the task of translating the work for the Anglophone world. Originally from Belfast, in the 1930s Daisy moved to the Soviet Union, where she worked as a translator. While there she married Padraic Breslin, who tragically became one of several Irish victims of Stalin’s Great Terror (see HI 7.4, Winter 1999, pp 37–9). Did Daisy realise that she was working with the words of a Soviet authority on Ireland? The answer is unknown. Daisy complained in her letters home of eyestrain incurred from reading about Lenin, however, so one assumes that it was not the most pleasant task.

As the gyre of terror turned, drawing many of his former comrades into its maw, Platon managed to avoid arrest. In 1938 he was dismissed, in a move that some have perceived as the prelude to falling lethally foul of the regime. Two years later another fate intervened. In 1940 the first Soviet historian of Ireland suffered heart failure. Decades after the revolutionary’s passing, Eoin MacWhite, an Irish diplomat trained in Russian by a political exile residing in rural Ireland, became the first English-speaking scholar to unearth Platon’s work on Irish history. Interviewing Padraic Colum, he drew out the poet’s recollections of his time living with the Bolshevik playwright. At the beginning of the twentieth century, with Europe subsumed within the maelstrom of the First World War, two couples were unknowingly poised before revolutions in their native lands. Each took divergent paths. The Colums built their lives in America, while the Lebedevs opted to partake once more in Russia’s revolutionary tumult. For Padraic Colum and Platon Kerzhentsev, however, the memory of their converging worlds in a boarding house on New York’s West Side evidently remained.

Maurice J. Casey is a graduate of the University of Cambridge and Trinity College, Dublin.

Read More:

‘Red Easter’

FURTHER READING

B. McGeever, ‘The Easter Rising and the Soviet Union’, https://www.opendemocracy.net/uk/brendan-mcgeever/easter-rising-and-soviet-union-untold-chapter-in-ireland-s-great-rebellion.

B. McLoughlin, Left to the wolves: Irish victims of Stalin’s terror (Dublin, 2008).

E. O’Connor, The Reds and the Green: Ireland, Russia and the Communist Internationals, 1919–43 (Dublin, 2004).