By Damian Shiels

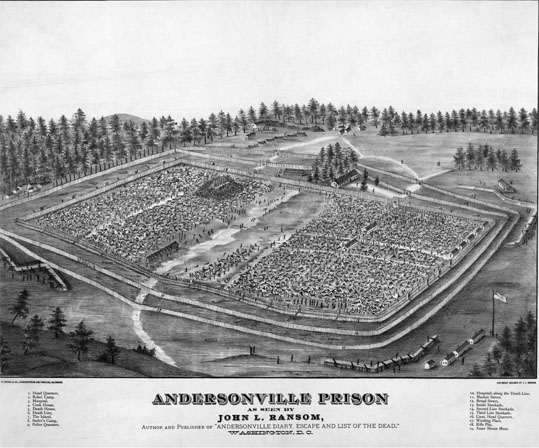

In a significant moment in Ireland’s remembrance of the American Civil War, on 19 October 2024 a memorial plaque was unveiled by an Irish delegation at Andersonville National Historic Site, Georgia. Andersonville—or Camp Sumter, as it was officially known—was one of history’s most infamous prisoner-of-war camps. Located in the rural south-west of the state, the prison was opened by the Confederacy in February 1864 and operated for just fourteen months. During that short period some 45,000 Union prisoners passed through its gates; c. 13,000 never left.

A mixture of exposure, want and disease transformed Andersonville’s 26.5 acres into the deadliest location of the entire American Civil War. The enormous scale of that mortality remains permanently etched into the Georgia clay, recalled by the thousands of small white headstones that now make up Andersonville National Cemetery. A significant number of those stones mark the final resting-places of Irishmen; this location cost more Irish lives than any of the battles of 1861–5.

Adding to the Andersonville plaque’s noteworthiness is the fact that it represents the first time the Irish state has remembered the impact of the American Civil War on Irish people with such a memorial. That significance was further reinforced by the presence of Minister Darragh O’Brien TD. Reflecting on the day’s importance ‘for Ireland in the United States’ in his dedication, the minister expressed his hope that the memorial would serve to ‘honour the memory of those who died here, to restore them the dignity of remembrance, to name them, and to root them in their home country’.

It was an effort to name the Irish dead and to research their lives and families that laid the foundations for the ceremony. In 2020 the Andersonville Irish Project was launched on irishamericancivilwar.com, an initiative that has to date identified more than 900 Irishmen who perished. The project maintains both a database of the identified men and an interactive map of Ireland, plotting locations linked with Andersonville victims. It is also conducting a wide range of analysis into the Irishmen who endured the prison, and their families.

Among the many stories emerging from the Andersonville Irish Project is the highly cohesive nature of Irish communities both at home and in service. One such example was revealed among a group of Irish prisoners serving in different Pennsylvania units who agreed to safeguard each other’s wills in the event of their death. Closer inspection of their service records revealed the bond that tied them together—all of them were from Donegal.

At a macro-level, the Andersonville Irish Project is reinforcing what we know about the extraordinary breadth of Irish US service. So far, Irish dead have been identified in almost 300 different units from 22 states and territories. Unsurprisingly, given its dominance as an Irish population centre, New York has by far the greatest representation. Likewise, demographic analysis is revealing the uneven nature of the prison’s impact on those incarcerated there, showing that Andersonville disproportionately killed older men. Almost 20% of the identified Irish-born victims were in their 40s or 50s, nearly 35% in their 30s. The youngest victims of all were boys who were at most 16; the oldest was Edmond Wool from Ballyphehane, Co. Cork, who was about to turn 65.

Cork is also the county with the highest percentage of identified deaths (13%), while Munster is the most-affected province (36%), but what has quickly become apparent is the all-encompassing and indiscriminate nature of Andersonville’s impact on Irish people. Amongst the National Cemetery’s dead are men from all 32 Irish counties and from every major religious background—Catholic, Church of Ireland and Presbyterian. It is appropriate, then, that the new Andersonville memorial is representative of all the island’s people. It was jointly funded by the Irish government and the Northern Ireland Bureau, and bears an inscription in English, Irish and Ulster-Scots.

See www.irishamericancivilwar.com/andersonville-irish.

Damian Shiels is a Research Fellow at Northumbria University.