By Ray O’Connor

Savings banks were financial institutions that promoted moral improvement among the lower social orders by advocating a strong work ethic, sobriety and thrift. They encouraged the poor to make financial provision for infirmity, illness and old age by offering a financial service that provided a safe place to deposit any savings. Savings banks were designed as a parallel banking system to private banks, which catered exclusively for the social élite. They were introduced for the emerging middle and lower middle classes—tradesmen, craftsmen, servants and factory workers of the industrial revolution—who operated at the lower end of the cash economy. The potential of such institutions to lessen demands for charity attracted the patronage of the aristocracy, the landed gentry and the clergy.

EARLY SAVINGS BANKS

The first savings bank was established in Hamburg in 1778. A second appeared in Berne in 1787. In 1798 England’s first savings bank was established in Tottenham. These early savings banks were the result of private initiatives that catered for local needs. They did not share a common history. The first two savings banks in Ireland belong to this category.

Savings banks, as we understand them today, emerged with the Revd Henry Duncan in Ruthwell, Scotland, in 1810. His model of banking, while streamlined by the Edinburgh Savings Bank in 1813, formed the basis for the savings bank movement in the United Kingdom. In 1816 this movement entered the island of Ireland, and 130 savings banks or savings bank branches were established in 123 locations in all 32 counties between 1816 and 1861.

REVD JOHN READE

Ireland’s first two savings banks were established as parish banks in the Dublin villages of Stillorgan and Clondalkin on 1 March 1815 and 1 January 1816 respectively by Anglican clergyman Revd John Reade (1766–1848). Reade was a curate in the parish of Stillorgan and Kilmacud between 1801 and 1815 and a minister in Clondalkin from 1815 until his death in 1848. He worked energetically to alleviate the plight of the poor. In Stillorgan he founded a school for poor children and a poor-shop. In Clondalkin he established another school and poor-shop as well as an almshouse, a Dorcas institution, which assisted widows by providing them with clothes and food, and a lying-in (maternity) hospital.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century Stillorgan and Clondalkin were rural parishes and agriculture was the primary economic activity. In Stillorgan and Kilmacud the land was devoted to grazing and was covered in meadow and pasture. The only non-agricultural employment was provided by a long-established brewery, which was purchased as a going concern by Henry Darley in 1802 and renovated and extended in 1805. The economy of Clondalkin was predominantly based on arable farming. Many resident landlords organised ploughing competitions and agricultural improvement societies. While a paper mill and limestone quarries provided some non-agricultural employment, the gunpowder mills on the Corkagh estate in Clondalkin, which had provided significant employment since their establishment in 1716, closed in 1815, just as Reade arrived in the parish.

Reade’s appointment in Stillorgan coincided with an economic boom triggered by demand for agricultural commodities to feed the British army during the French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15). The inflated prices commanded by agricultural foodstuffs ensured that Ireland enjoyed a period of unprecedented prosperity. The benefits of the boom trickled down to lower social classes. As private banks catered only for the upper echelons of society, the demand for the services offered by savings banks—a safe and secure institution where poorer classes could deposit surplus funds—is understandable. The Stillorgan savings bank established by Reade met this demand and was in ‘a very flourishing state’ when Reade was reassigned to Clondalkin.

INSPIRATION?

While nothing is known about where Reade acquired the idea for these banks, the fact that he referred to them as the Stillorgan Parish Bank and the Clondalkin Parish Bank suggests that he may have been influenced by a pamphlet written by Revd Henry Duncan, founder of the Ruthwell Parish Bank in Scotland, whose Essay on the nature and advantages of parish banks, for the savings of the industrious, published in January 1815, outlined the governance and objectives of such banks. Beyond the name ‘parish bank’, however, there is little similarity between Reade’s savings banks in Stillorgan and Clondalkin and Duncan’s parish bank in Scotland.

Reade probably called them parish banks not because he was influenced by Duncan but simply to delineate the area from which the clientele could be drawn. Interestingly, Duncan, in a revised edition of his pamphlet published in 1816, observed that some Scottish clergymen informally engaged in ‘collecting the little earnings of their poorer parishioners and placing them in situations of security and profit’. He indicated that, unknown to him, such a savings bank was established in 1807 by Revd John Muckersy in West-Calder in Scotland. There is no reason why Reade might not have offered a similar service in Ireland. The two parishes in which he served offered paid employment to those who laboured in Darley’s brewery, the paper mill, the limestone quarries and the gunpowder mills. Such paid employment was the exception rather than the rule in rural areas in early nineteenth-century Ireland.

Reade’s two savings banks operated independently of the wider international and Irish savings bank movement. Despite his experience and expertise in operating them, he neither made any effort to engage with those seeking to promote savings banks at a national level nor was approached by them for advice when savings banks spread across the country from 1816. He was not invited to become a member of a society that styled itself the ‘Friends to the Establishment of Savings Banks in Ireland’, which held its inaugural meeting on 10 February 1816 in Dublin and was composed of 21 top-ranking Anglican clergy, businessmen, merchants, bankers and financiers.

MODE OF OPERATION

What made Reade’s savings banks unique was the way in which they operated. He based both banks in the glebe house. In 1818 Francis Burdett described how the Clondalkin bank operated:

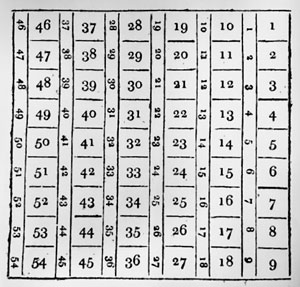

‘The money is deposited in large flat tin cases; each case is two feet long by one and a half feet wide, and three inches deep, containing 54 compartments, in every one of which a little book (made by Ladies) is placed, with its number on the cover, in its respective receptacle, with a correspondent number on the division, as in the following outline: [see image on p. 23]. In each of these Books, the respective sums, that have been lodged by the poor from time to time, are entered, with an account also of what is drawn therefrom; the poor are given Duplicate Books in which similar entries are made.’

While visitors to the bank agreed that it met the needs of the poorer classes, they argued that Reade should have used the money on deposit for charitable purposes rather than allowing it to lie redundant in a tin box. They believed that the savings bank took much-needed money out of circulation. Reade understood this assessment but saw dangers in following this advice:

‘No doubt this might be the case; still the good purposes of the Bank would, I fear, be greatly defeated. The poor are always better pleased to see their money at every period when they make a deposit, and they, on that account, like to increase their little Capital, and are excited to such industrious pursuits as will enable them to do so.’

He believed that for his savings bank to succeed the fundamental issue was that of trust. He understood the psychology of his clientele. If depositors came to the savings bank and their money was missing—on loan or deployed for charitable purposes—they might not understand and might immediately demand their money back.

DISAPPEARANCE

The banks would soon disappear. In 1818 Reade wrote that ‘under very unfavourable circumstances, the Clondalkin Savings Bank has been attended with much advantage to the poor’—the ‘unfavourable circumstances’ being the deepening post-Napoleonic economic recession. Even though the tin case allowed for only 54 clients, the numbers using the bank had risen to 70 by 1818. This shows that the poor trusted Reade with their savings and took advantage of the interest rate he offered:

‘I give the poor 5 per cent for Savings above 10s. and when they accumulate to One pound and upwards, I buy Government Stock, in my own and their names, for which I receive the Interest for their use. The small sums in my Bank are never made use of, and the interest allowed on them is in the aggregate so trifling, that it is given to the poor as a premium for their frugality.’

Nevertheless, it is quite telling that in a parish of over 2,000 people only 70 individuals had deposited money in a savings bank that had operated for over two years. It illustrates just how small a clientele this bank assisted and may explain why Reade slowly lost interest in the venture. The time invested was not proportionate to the benefits derived. As Europe and Britain urbanised, industrialised and transitioned to a cash-based economy, savings banks had an important role to play. In Ireland, 85–90% of the population lived in rural areas and remained engaged in agriculture. There was a very limited amount of money in circulation among the poorer rural classes. As the post-1815 economic recession deepened, many who had engaged to some degree with the cash economy during the economic boom reverted to the cashless economy. Agricultural labourers worked for food and shelter, not cash. Savings banks were not a service they required.

Despite claims to the contrary, there is no evidence to support the idea that savings banks diffused from Stillorgan and Clondalkin to the rest of Ireland. Apart from these two savings banks, the earliest in Ireland were established in Ulster, where the idea had been imported from Scotland. After the Belfast Savings Bank was established on 6 January 1816, it acted as a model for others. The savings banks in Stillorgan and Clondalkin had little if any influence. Both disappeared quite quickly from the historical record. While they are recorded as still ‘thriving’ institutions in 1818, after that date they are not included in any lists of savings banks submitted in parliamentary returns. The evidence suggests that both were short-lived institutions.

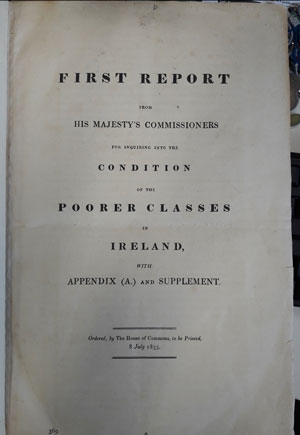

Between 1833 and 1836 the Royal Commission on the Condition of the Poorer Classes in Ireland distributed a questionnaire survey to all Anglican clergy in Ireland. This survey represented a major source of information for the Poor Inquiry (Ireland) (1836) and included a question about savings banks. Intriguingly, Reade as minister in the parish of Clondalkin made no reference to his early savings banks in his reply. He simply stated that ‘there is no savings bank in this parish. Instalments at the poor-shop are preferable, as the advantages to the poor are greater.’ This suggests that Reade realised that in the post-Napoleonic economic downturn those who might benefit from savings banks represented a declining proportion of an increasingly impoverished population. His philanthropic energies were better deployed elsewhere, like the poor-shop he specifically mentioned in his reply. Similarly, Revd R. Greene, replying for the parish of Stillorgan and Kilmacud, wrote: ‘In the adjoining parish of Monkstown there is a savings’ bank [located in the village of Blackrock], of which my parishioners avail themselves: servants the chief contributors. The bank very prosperous.’ This demonstrates that the first-ever savings bank in Ireland had long since faded from memory. The fact that Reade did not reference the existence of either the Stillorgan or Clondalkin savings banks for a government-commissioned inquiry suggests that he saw his savings banks as not being part of the wider network that emerged in the wake of the Belfast Savings Bank. Ironically, while there is no memorial or commemorative artefact to Revd John Reade, who introduced savings banks to Ireland, the philanthropic endeavours of his son, Revd David John Reade, who succeeded his father as rector of the parish after his father’s death in 1848, were commemorated in a plaque on former almshouses (now Church Terrace) on Monastery Road, Clondalkin.

Prosperity driven by the high prices commanded by agricultural commodities as well as the presence of some manufacturing industries in both parishes prompted Reade to establish the savings banks. As economic conditions deteriorated after 1815 and levels of impoverishment increased, Reade appeared to have grasped that the window in which savings banks might have had relevance in Ireland had closed. Savings banks were introduced into Ireland at the beginning of a prolonged economic recession. Those who ultimately benefited most from savings banks were not the social groups at which they were targeted. Repeatedly in the Poor Inquiry (Ireland) (1836) Anglican ministers refer to savings banks where depositors were ‘rather above the class originally designed to be benefited by such institutions’ and where ‘the depositors belong to other and higher classes’. Once Reade understood that the benefits to the poor from other forms of charitable and philanthropic institutions outweighed those of savings banks, he rapidly lost interest in them.

Ray O’Connor is a Lecturer in Historical Geography at University College Cork.

Further reading

Kerry Evening Post, ‘Death of the Rev Doctor Reade’ (obituary), 9 February 1848, 2.

W. Lewins, A history of banks of savings (London, 1866).

E. McLaughlin, ‘“Profligacy in the encouragement of thrift”: savings banks in Ireland, 1817–1914’, Business History 56 (4) (2014), 569–91.

C. Ó Gráda, ‘Savings banks as an institutional import: the case of nineteenth-century Ireland’, Financial History Review 10 (1) (2003), 31–55.