By Neasa MacErlean

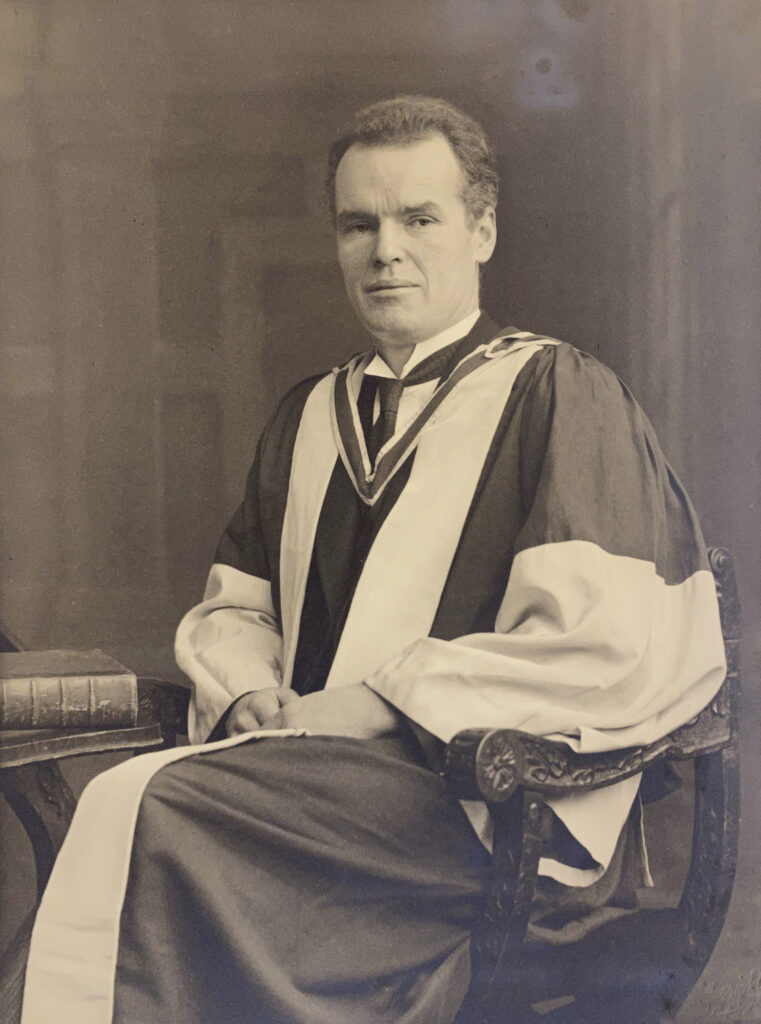

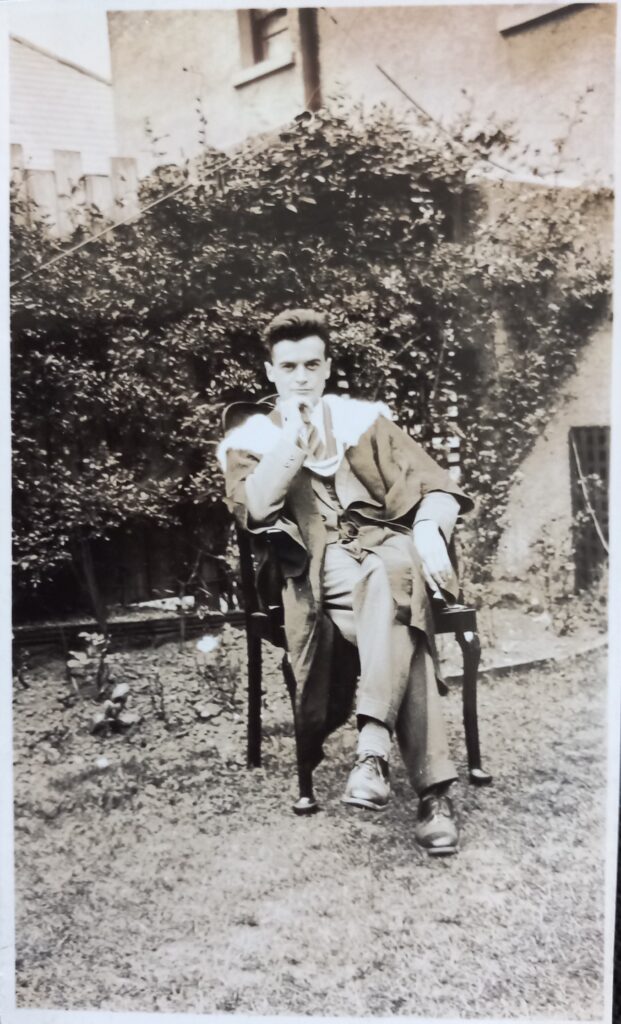

Robert Dudley Edwards is known as much for his eccentricity as for his work in professionalising the study of Irish history. Stories are still recounted about the famous Marathon exam that he instituted at UCD, the departmental meetings in Hartigan’s pub, his encounters with the Gardaí and cryptic comments delivered to startled students. But did something else lie behind the quirky behaviour?

Two examples are particularly interesting. At Mass in Dublin, he would read a book in the back pews. One of his favourite church-time authors was the Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a Darwinist who seemed destined for the Forbidden Books Index but managed to avoid it. Speaking from his own pulpit at University College Dublin to the exponentially growing numbers of history students, Dudley (as my grandfather was affectionately known) often preferred posing questions to providing answers. And the questions that he put to his audiences ranged from the nearly unintelligible to the deceptively simple (‘What is an Irishman?’).

QUAKER BACKGROUND

Both of these examples, however, derive more from his Quaker background than from an innate strangeness of character. Quakers are free to read during their gatherings (‘meetings’), and it is common for books to be left on the table in Friends’ meeting houses for this reason. By confining himself to works on religion during Mass in Clontarf, Dudley was conforming to this tradition. And, regarding the emphasis on questions, the Quakers remind themselves of their aims not by reciting a credo of beliefs but by interrogating themselves—in particular through eleven Queries that they examine each year in their hearts.

The scientific history revolution which Dudley and Theo Moody, his counterpart at Dublin’s Trinity College, began in the 1930s partly derived from advances made famous by the 1921 Nobel Prize-winner Albert Einstein. Dudley shared a non-doctrinal attitude to religion and a questioning approach with the Swiss-German physicist. ‘Don’t listen to the person who has the answers; listen to the person who has the questions’, Einstein is reported as saying, but Dudley could have made that comment too. Unanswerable questions (‘What happened before the Big Bang?’) dominate astrophysics, but Dudley believed that they also apply in history because it is impossible for any individual to provide completely unbiased responses. In their teaching, Dudley and Moody put the emphasis on what was provable, and this saw facts and analysis replace myth as the starting-point for study.

A THIRD MUSKETEER

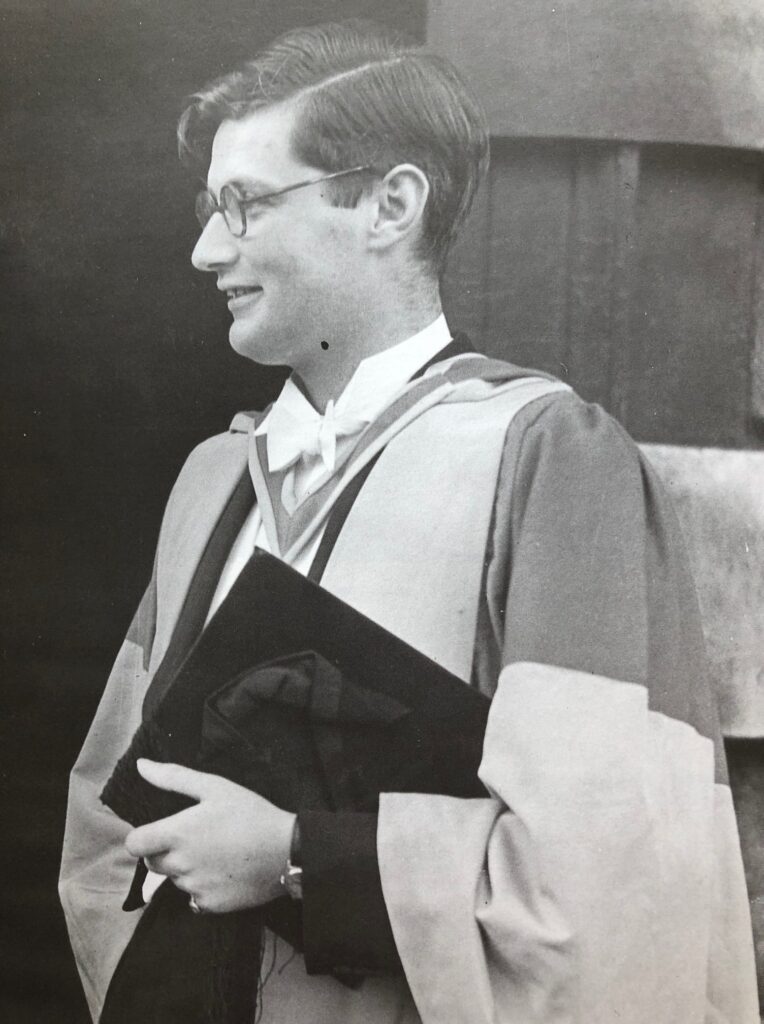

Alongside Moody and Dudley there was, in Dudley’s words, a third Musketeer who joined them at the heart of the shift to scientific history. This was David Beers Quinn, who would specialise in the colonial exploration and appropriations of the British Empire, join the Communist Party and leave it for Labour. He later became Professor of Modern History at Liverpool University. All three Musketeers wrote their doctoral theses at the newly founded Institute of Historical Research at the University of London.

What is really surprising about the trio is the common theme of deep links with Quakerism. Moody, born into the Plymouth Brethren sect in Belfast, became a Friend after he moved to Dublin, attending the meeting house in Churchtown and reorganising the Quaker Historical Library. Quinn, from a Church of Ireland background, passed his first fourteen years on the Quaker estate of the Goodbodys in Clara, Co. Offaly, where his father was head gardener at Inchmore. The Goodbodys, alongside the Bewleys, the Richardsons (linen mills) and the Jacobs (biscuits), were one of the most famous Quaker families in Ireland. Quinn attended the Sunday Quaker meeting. Dudley’s rumbustious mother, Bridget, was a Catholic from County Clare, and his gentle English father, Walter, started life as a Methodist from the Malvern Hills and ended it as a Friend, one of the members of the largest Irish Quaker meeting house, Eustace Street, in Dublin. Walter’s gift to his ten-year-old son of H.G. Wells’s The outline of history put Dudley on his chosen course early on. But, although he absorbed Quaker ways and attitudes from this beloved parent, he was Catholic in the outside world. A Quaker would not have become Professor of Modern Irish History at UCD in those years, and his academic career would have been over before it began. Dudley and his family were aware of the need to compromise and be diplomatic on issues such as this.

ANTI-VIOLENCE

The probability of even two people coming together from this small group is about one in a million. In the 1930s Irish population of about 4.3 million there were 2,500 Quakers or, we could extrapolate, about 5,000 within the Quaker ambit, as these three were. So we can fairly safely assume that what drew them to their missions in life, and to each other, was not coincidence. From the work they carried out afterwards we could say that they were looking for alternatives to the mass slaughter of the Second World War and to mass poverty. A theme that was particularly marked in the main two, but possibly less so in Quinn, was that of the Quaker stance of anti-violence. The entry for Moody in Richard S. Harrison’s A biographical dictionary of Irish Quakers says: ‘He hated violence but spent much of his life studying the causes and effects of it’. As a young debater in UCD’s Literary and Historical Society, Dudley explained his views: ‘War never achieved anything but compromises, and they could be secured very well by diplomats’. And, referring to the two of them, Professor Aidan Clarke of Trinity said: ‘Their motives transcended the disciplinary: both were convinced of the ameliorative power of an informed and objective understanding of the past’.

Each of the three men was so dedicated to these ideas that their university roles could be seen as the launch pad for broader aims. Quinn was also deeply involved in Irish Historical Studies, the professional journal which the other two launched in 1938. But they were so subtle in their anti-violence beliefs that it was only seven decades later that Dr David Edwards (no relation) detected the underlying trend in IHS, as he noted in the 2007 book he co-edited, The age of atrocity: ‘Founded by two early modernists, it is hardly surprising that it gave generous coverage to some of the main developments in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Ireland. Significantly, however, it was not until forty years had elapsed, and both the founding editors had resigned, before an article appeared in the pages of IHS that directly addressed the violence and the bloodshed, the bigotry and the atrocity, of early modern times.’ Other Dudley–Moody projects had similar, unspoken aims—particularly securing Ireland’s membership of the Comité International des Sciences Historiques (with the financial and political backing of Éamon de Valera) and developing Dudley’s proposal to Dev for a Bureau of Military History. Dudley’s championing of archives, which led to the creation of UCD’s depository and then the National Archives, was intended to tie history to the reality of the past rather than imagination.

Whenever possible, the two or three Musketeers operated on a 32-county level. One of the reasons why Dudley was so attached to the Royal Irish Academy was its cross-border coverage. And, of course, when in 1950 he established the Irish Inter-Varsity History Students Congress it was north–south. Professor Art Cosgrove, then a history undergraduate at Queen’s University, Belfast (and later to become UCD president), attended his first in 1959. Dudley, he said, ‘wanted to build bridges with the North. He succeeded.’ Dudley saw this as one of his main roles in life, as he wrote in The Leader in 1955: ‘One of the few small services for mankind which the study of History can offer is to break down prejudices which have survived from the past. Between neighbouring communities the perpetuation of disagreement is only too often due to misreading the past or perhaps to continuing to believe in war propaganda.’

LEGACY?

So, what traces did this quiet campaign leave behind? Many, even if it saw the return of what it had worked hardest to avoid—the re-emergence of violence—during the Northern Ireland Troubles. Even now, however, we see how actions from the Quakers and the Irish state sometimes dovetail—in their recognition of the genocide happening in Gaza, for example. In December Micheál Martin, a historian and now taoiseach, secured government approval for Ireland to join South Africa’s International Court of Justice case against Israel under the Genocide Convention. Two weeks later, American Quakers were forced to withdraw an advertisement from the New York Times when it refused to accept use of that word. It began: ‘Tell Congress to stop arming Israel’s genocide in Gaza now!’

Many other aspects of Dudley’s teaching reflected Quaker beliefs—his recognition and promotion of women (often described to me as the ‘superior sex’), his interest in archives and a non-hierarchical view of mankind. Irish Quaker families can often trace their genealogy back to before 1700. Quakers believe that each soul has its share of divinity (rather than Original Sin), and the recording of births and deaths is tantamount to tracing the human manifestation of that Higher Power. Dudley’s edgy relationship with the Catholic Church reflects a discomfort with a hierarchy that he saw as unjust. Although he would do what was needed in public—such as kissing Cardinal Conway’s ring—at home he referred to the cardinals not as ‘Your Eminence’ but as ‘Your Opulence’. Media historian Felix Larkin is one who sees a healthy irreverence as ‘a hallmark of the UCD historians’, one which he links directly to Dudley’s personality. Dudley often made his serious points as jokes—such as his fancy-dress appearance as a nun, having borrowed a Dominican wimple from his colleague Margaret MacCurtain (Sister Benvenuta) in or around 1965. A convinced Catholic might not have risked such controversy.

Being anti-violence was potentially a dangerous game in itself in a country whose earlier heroes carried guns. During his life Dudley staved off political attacks on him which could have undermined the infrastructure he had helped build in history. But the fury behind Father Brendan Bradshaw’s attack on ‘value-free’ revisionism, begun five months after Dudley’s death in 1988, shows the depth of loathing against him for, said the Marist priest, depopulating history of ‘heroic figures, struggling in the cause of national liberation’.

Dudley was a serious subversive, but he knew that by presenting himself as a man with quirks—something of an intellectual clown—he would have more freedom to express his true views.

Neasa MacErlean is a journalist and the granddaughter of Robert Dudley Edwards.

Further reading

D. Edwards, P. Lenihan & C. Tait (eds), Age of atrocity: violence and political conflict in early modern Ireland (Dublin, 2010).

N. MacErlean, Telling the truth is dangerous—how Robert Dudley Edwards changed Irish history forever (London, 2025).