RTÉ1, 21 August 2021

By Donal Fallon

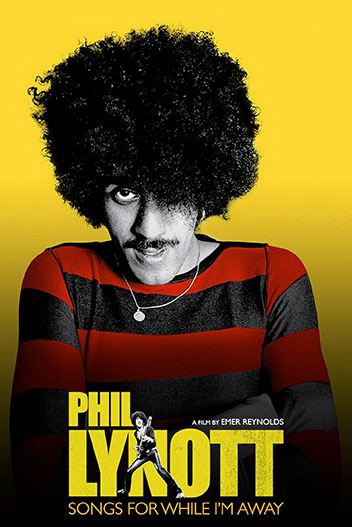

Emer Reynolds’s documentary opens with shots of contemporary Dublin, showing us Phil Lynott’s place in the iconography of the city—the painted light-boxes, the prints, the murals and more besides. From the streets of suburban Crumlin to the city centre, we see images of Lynott everywhere, reminding us that he is perhaps only second to the Poolbeg stacks as a symbol of the city in the eyes of many. One place where Phil’s face was omnipresent towards the end of 2020 was on the side of buses, advertising a cinema release for this documentary. Alas, it would be well into 2021 before that happened. Songs for While I’m Away has the unique distinction of being still on cinema screens when shown on RTÉ.

Songs for While I’m Away does not utilise a narrator, instead drawing on rich archival findings—including archive audio of Phil himself—and the assembled interviewees. In this touching tribute to Lynott, Reynolds has assembled a cast that includes voices familiar to the narrative—like artist and designer Jim Fitzpatrick and Hot Press editor Niall Stokes—and voices that will be new to many of us, including Phil’s daughters, Cathleen Crowther-Lynott and Sarah Lynott.

One of the other voices that we hear from the archives is that of Philomena, his mother. Her insights into being the young mother of a mixed-race and ‘illegitimate’ child are a reminder of the important societal context in which this story is told. Likewise, Phil’s relations and friends from Crumlin paint a picture of working-class life—and the escapism of music—that is vital to understanding Lynott. There is real warmth in the recollections of Gus Curtis, a childhood friend, and through his words and little-seen images of a young Philip playing amidst the housing estates of Crumlin there is much here that is new concerning his working-class childhood.

Refreshingly, the documentary touches briefly on the showband scene in a manner that is not dismissive but instead understands the importance of such bands in formulating friendships and social networks which would go on to produce some of Ireland’s most formidable musical talent, including Rory Gallagher, Van Morrison and Thin Lizzy. One journalist has written of the ‘dead weight of the showbands epoch’ as something that Irish music would eventually shake off, but it is perhaps better viewed as a training ground for much of what followed. Tony Browne’s history of that scene, the brilliantly titled Send them home sweating, similarly captures its importance.

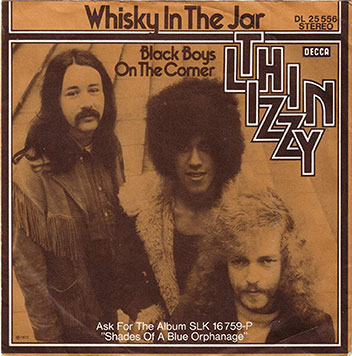

Moving on from Lynott’s childhood, the documentary quickly shifts the focus to Thin Lizzy—indeed, at its core it is much more the story of the group than of Lynott alone. Their rise was not meteoric but rather a series of little successes that opened the door to Britain. One of the most moving scenes of the documentary utilises Lynott’s song Dublin (‘How can I leave the town that brings me down, that has no jobs …’) amidst footage of the familiar emigrant journey and the boat. It’s clear that while Dublin was at the core of Lynott’s identity—and that of the group—leaving it would be essential to the success of the band. When that breakthrough single came, it came—unusually for a band who took pride in the creation of a unique sound—in the form of a cover version of a folk standard, Whiskey in the Jar. In time, it grated on the band, but the cheques and profile increased.

Of those interviewed, the most touching and revealing are, unsurprisingly, former lovers, childhood friends and bandmates. Caroline Crowther, mother of Phil’s two daughters, talks frankly of the stresses of raising the children at the Sutton home that Lynott had purchased for the family but which he was seemingly never in, while recording in Britain and touring internationally. ‘It was like I swapped countries’, the English-born Crowther tells us. There are other interviews—with James Hetfield of Metallica and Adam Clayton of U2, for example—which, while lacking the same level of intimacy, bring their own important insights into the lives of musicians. Amidst the impressive line-up of voices, however, there are interviews that seem like missed opportunities. Jim Fitzpatrick, as well as being a close friend of Lynott (the capacity in which we meet him here), was the creative force behind the iconic aesthetics of Thin Lizzy. Lynott’s obsession with Celtic mythology, and the image he constructed of himself and the band, is something that Fitzpatrick could have waxed lyrical on.

Phil Lynott has been the subject of several biographies—the finest being Graeme Thomson’s Cowboy song: the authorised biography of Philip Lynott. But while Thomson’s biography makes no fewer than fifteen references to heroin, which ultimately played no small part in Lynott’s demise, the drug is not explicitly mentioned once in Songs for While I’m Away. There are references to ‘the drugs’ that entered the life of the band, but what those drugs were is never expanded on. Thomson tells us in his biography how ‘Lynott was injecting heroin into his toes and legs to avoid marking his arms, but to anyone paying close attention his addiction was blindingly obvious’.

All in all, Reynolds’s documentary is a beautifully produced love-letter to Lynott—and about this she has been open and unapologetic. She understands that every documentary, like any other study, is about chosen narratives. In discussing her film, she has made the point that talk of that addiction was ever-present in discussions of Lynott and that ‘It was very sad that that was the narrative, as opposed to the narrative of his amazing rise, of his talent’. Songs for While I’m Away is a great telling of the amazing rise of Phil Lynott—but what of the sad fall? Lynott’s rise is one of the great Dublin stories, which still endears him to the city today as a working-class hero. Unfortunately, there is something deeply Dublin in his succumbing, too, to a drug that blighted the city and the lives of its young.

Donal Fallon is a historian and presenter of the ‘Three Castles Burning’ podcast.