Trevor Parkhill

Kings in Conflict catalogue, Ulster Museum.

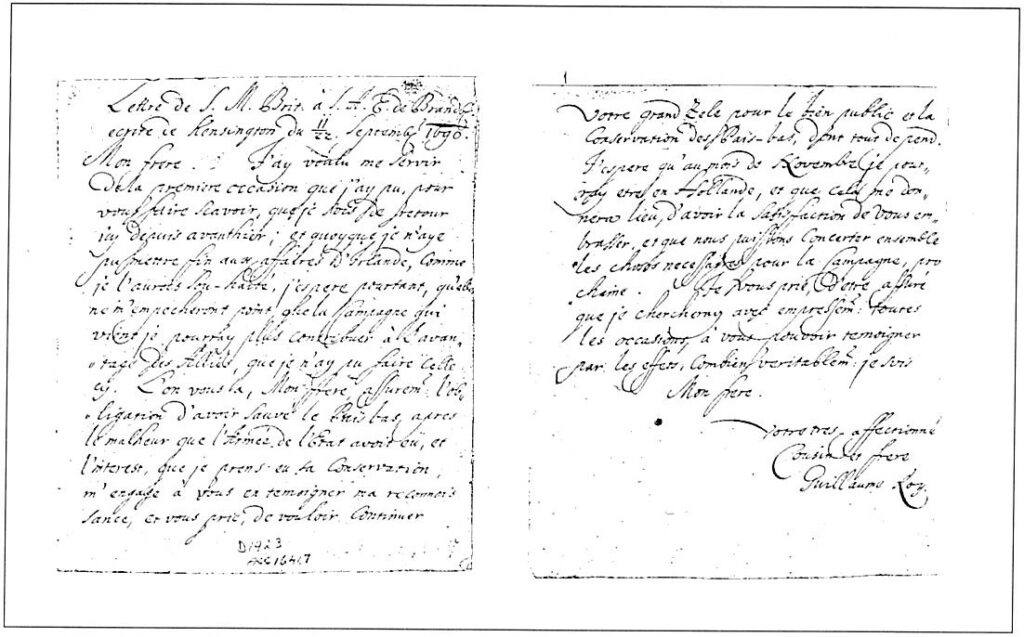

The documentary evidence in PRONI reflects the European context of the war in Ireland. For example, a letter in September 1690 from William to his cousin, Frederick III, Elector of Brandenberg, outlines his anxiety to be finished with business in Ireland and to return to Europe as quickly as possible:

and although I have not been able to finish affairs in Ireland as I would have wished, nevertheless I hope that they will not prevent me from contributing to the forthcoming campaign to the better advantage of the allies than I have been able to do so far. [translation] (D.1923).

For both kings the fighting in Ireland was principally a means to an end. Neither James nor William cared particularly about Ireland and the people who lived on the island. James came to Ireland solely as a means of regaining his English throne, William solely to defeat James, secure the crown and return to Europe and the conflict with Louis.

Frederick III,Elector of Brandenburg outlining his anxiety to be finished with business in Ireland.

The Armies

When James arrived on 12 March 1689 from France, with about 1,800 men, he was joined by 2,000 of the Irish standing army and ‘nearly as many Raparees’ (Jacobite irregulars). By this time, all but the north-west of Ireland was in Jacobite control. James planned to crush the remaining Williamite forces before invading England. The siege of Londonderry, however, greatly impeded these designs, not only in delaying James but because of the casualties suffered by the Jacobites.

The Duke of Schomberg, William’s Huguenot general, arrived in Ireland in August 1689 and immediately took Carrickfergus which until then had been held by Jacobites. He was a naturally cautious military commander, now aged 75, and he was outnumbered by James’s forces. The campaign in 1689 saw both sides reluctant to engage in full-scale battle. Effectively, the failure of the Jacobites to capture Londonderry and Enniskillen meant that James’s planned invasion of England would have to wait another year. The armies prepared for a winter of inactivity.

The Williamite forces were quartered mainly at Lisburn. The evidence indicates that predictable problems of indiscipline occurred, so that Schomberg was obliged to issue a printed proclamation forbidding ‘the horrid and detestable crimes of prophane cursing, swearing and taking God’s holy name in vain’. (T.1052)

Both sides received reinforcements in March 1690. Louis agreed to support James, and sent men and arms for the summer campaign of 1690. In March 1690, some 7,000 Danish troops, commanded by the Duke of Würtemberg, arrived in the north. The fearsome reputation which the Danish army had throughout Europe was commented on in a letter received by Belfast Quakers in April 1690; ‘the Danes have struck a terror in the Irish at their landing because of the old prophesy that though under protection they have fled from their ploughing and sowing. James issued a proclamation declaring it should be death for any man to report that the Danes had landed’. (T.1062)

Schomberg was killed at the Boyne (probably by ‘friendly fire’) and was replaced by Baron de Ginkel, some of whose letters, written during the 1691 campaign, are held in PRONI. Ginkel was an experienced professional soldier who, in his letter to the Lords Justices of Ireland three days after his crucial victory at Aughrim in July 1691, states simply: ‘It was a great victory we had over the Enemys… We must loose no time now. I hope the £2,400 for the subsistance of the army will come soon…’ The letters also show that Ginkel observed a strict code of conduct over prisoners. In his letter from the ‘camp at Athlone’, 5 July 1691’, he refers to a Major General Maxwell who was taken at Athlone:

The time he has been prisoner, I have had severall occasions of conversing with him and find … he is a man of meritt and understanding, I must recommend… that he may be treated with all civility that his circumstances will bear.

He also says that the Jacobite leader:

Monsr St Ruth having sent ye Count Paulin into France, which is a breach of all commerce between us… if anything is done to that Gentlemen in France, I shall be obliged to revenge it upon the French prisoners that wee have made (D.638)

The Siege of Londonderry

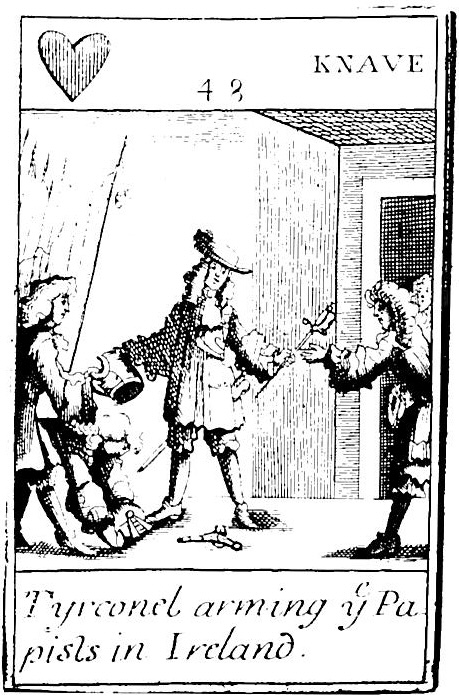

The Apprentice Boys of Derry had shut the city gates on 12 December 1688. The response of Tyrconnell, the Jacobite Commander-in-Chief, was to alert the northern Jacobite leader, the Earl of Antrim, to prepare to suppress the revolt. Writing to Antrim on 18 December 1688, Tyrconnell observes:

Finding the people of Londonderry continue obstinate in their rebellion, and that there appears no likelihood of reducing them by fair means I desire your lordship to give orders presently, to all the companies of your regiment, to be in readiness to march at an hours warning, it being my resolution in case I doe not hear, by fridays post, that the City of Derry has submitted, to order them, with severall other regiments of horse, foot and dragoons, to march against it, and will soon follow them myself. Three paquets came in this morning but brought very little news. The King is at Windsor in the head of his Army, which lyes all along the Thames. The Prince of Orange is about Newbury. The Queen and the Prince are at Whitehall. (D.2169).

The letter reveals Tyrconnell’s determination to quell the ‘rebellion’ (against James, who was still king) in Londonderry. This effectively marks the beginning of the Williamite war in Ireland. By the time James II arrived in Ireland in March 1689, the whole country, with the exception of the north-west, was in Jacobite hands. It is also worth noting that Tyrconnell, by referring to both ‘Derry’ and ‘Londonderry’, does little to resolve one of the more inconsequential controversies in modern Ulster idiom.

Between April and 31 July 1689, the city was subjected to the famous siege and, in the weeks from mid-June, conditions became intolerable. A French Jacobite, De Pointis, constructed a barrier across the river which was eventually broken by the Mountjoy, commanded by Sir John Leake. The boom prevented supplies from getting through to the inhabitants. The account of James Lenox in PRONI lists the food and materials owned by him which ‘the garrison of Derry in ye laying of the Siedge’ used, and for which he sought compensation. (T.3161).

The devastation of Londonderry at the end of the siege is evident in the minutes of the first full meeting of the Corporation after the end of the siege on 19 September 1690:

Then alsoe a petition resolved and voted to be drawne and referred to his Grace ye Duke of Schonberg, Lord Generall and Genll. Governor of Ireland, for some subsistence for the poor Inhabitants of this City that remained here all ye siedge and are now alive in it.

At another meeting, the re-building of the city was discussed:

Upon a motion concerning the ruinous state and condition of this City by reason of the late Siege, and the utter inability of many of the inhabitants therein to repair their respective tenements, much less to rebuild those that are beat down by the Bombs. Ordered that a letter may be sent to the Society, representing the same and urging their care in taking some effectual speedy course for the promoting of such repairs. (LA.79/A/l)

The Boyne And After

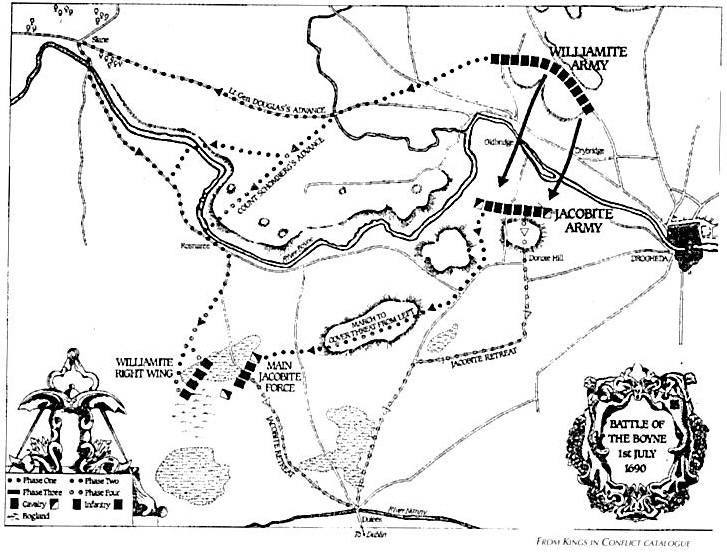

William of Orange landed at Carrickfergus on 14 June 1690 to take command of his army. He brought with him 15,000 troops, which meant that there were 36,000 Williamites against 25,000 Jacobites at the Boyne. On the eve of the battle, William was grazed by a bullet but quickly put paid to rumours that he had been killed.

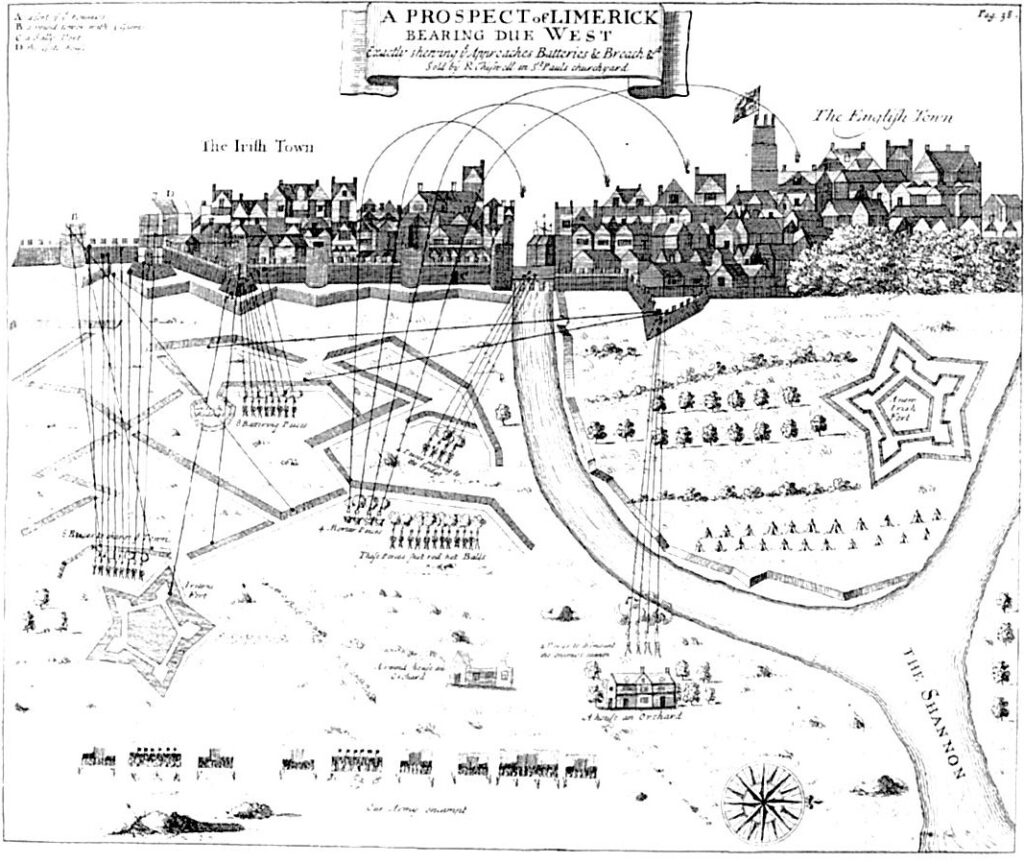

On the morning of 1 July, 10,000 Williamite troops led by Meinhardt Schomberg, the Duke’s son, marched up river to Rosnaree on the river Boyne. Tyrconnell was convinced that the main threat would come there and moved more than half his army in that direction. This allowed the main body of the Williamite army to wade across the river. The Jacobites were outnumbered and forced to retreat in disarray. It is estimated that some 1,000 Jacobites were killed and about half that number of Williamites.

James returned to France, his hopes of invading England shattered. The Jacobite leaders, notably Patrick Sarsfield, decided to continue the struggle. They regrouped their forces at Limerick, which they held throughout the winter of 1690-91. Baron de Ginkel succeeded Schomberg as Williamite leader and led the 1691 campaign. The letters from de Ginkel which are in PRONI testify to his professional conduct of the campaign. His greatest success, and the most severe loss for the Jacobites, was the Battle of Aughrim, fought on 12 July 1691. The Jacobites successfully defended Kilcommadan Hill outside Aughrim until their brilliant leader, St Ruth, was unluckily killed at a crucial time. The Williamite cavalry, led by Marquis de Ruvigny, took advantage of Jacobite hesitation and snatched victory when defeat seemed likely. It is estimated that over 7,000 Jacobites, including many sons of leading Irish families, were killed in the terrible scenes which ensued.

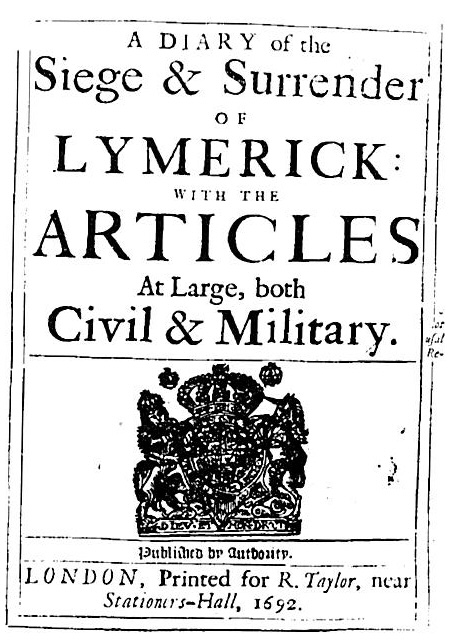

The Treaty of Limerick

After the carnage at Aughrim, the Jacobite forces withdrew to Limerick. When Tyrconnell died (of natural causes) and the promised help from France did not arrive, the other Jacobite leaders were tempted by the favourable terms offered by Ginkel to the garrison at Galway in July, and wanted to negotiate a peace. On 26 September 1691, the fighting stopped. Ginkel’s terms formed the basis of discussions with the Jacobites’ leader, Patrick Sarsfield, Earl of Lucan. The Treaty of Limerick was drawn up, containing civil and military articles.

The civil articles guaranteed the property of Jacobite landowners still in arms at Limerick, and that Irish Catholics would have protection for their religion. The military articles offered the Irish Jacobite soldiers three choices. They could return to their homes in peace; join the Williamite army and serve with it in Europe; or go to France and fight for Louis.

Those who decided to join King James in exile in France were given free transport for themselves and their families. Between October and December 1691, it has been estimated that some 12,000 ‘Wild Geese’ went into exile, many of them in ships, as Ginkel’s correspondence shows, provided by the Williamites.

In the course of the 1690s, it became apparent that the terms of civil articles were not going to be strictly kept. Although the Treaty guaranteed the Irish who fought at Limerick that they would not lose their lands, William confiscated over 750,000 acres from James’s supporters to reward his own followers. In turn, the English House of Commons forced him to cancel these grants and the lands were sold off to pay for the war. The ‘Broken Treaty’, as it became known, and the exile of the Wild Geese, created the bitter background to the introduction of the Penal Laws.

William’s Irish Parliaments

Regular parliamentary sessions began during the reign of William III. The Irish parliament had not been an integral part of government in 17th century Ireland. The Irish privy council in Dublin governed on its own. There were frequent parliamentary sessions after 1688 because of the King’s need for additional taxation to supplement the permanent or ‘hereditary revenue’. This additional money was used to finance William’s war against Louis XIV of France – The War of the League of Augsburg 1688-97. The expense of maintaining an army in Ireland as a strategic reserve broke the Irish executive’s independence of parliament. Irish parliamentarians established their right to sit regularly (two years became the usual interval between sessions) because they had control of the purse-strings. By 1715 the Irish parliament had become an indispensable institution of government.

The Penal Laws

Correspondence and papers in PRONI, chiefly from the Foster/ Massereene archive, reveal some of the factors behind the passing of the Penal Laws as well as the consequences of their enforcement. There is also an important collection of papers in PRONI which describe an event which occurred on 6 June 1739. On that day Father John Fottrell, Provincial of the Irish Dominican Friars, was arrested at Toome, Co. Londonderry. As happened on a number of occasions during the penal era when the authorities chanced to lay hands on an embarrassingly high-ranking Catholic functionary (in Fottrell’s case, a man of ‘international consequence’), he was allowed to escape from jail. But his papers remained behind in the hands of the over-zealous Co. Londonderry J.P. who had made the arrest, George B. Conyngham, and were later deposited in PRONI.

These sources are available at the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. There is also a good range of illustrative material, including views of battles at Londonderry, the Boyne etc. and images of William, James, the Duke of Schomberg etc, in T.1129 which could be useful to teachers seeking visual as well as documentary sources.

Trevor Parkhill is Principal Records Officer, PRONI, Belfast.

Further reading:

W.A. Maguire (ed.), Kings in conflict; the revolutionary war in Ireland and its aftermath (Belfast 1990).

John Miller, James II; a study in kingship (London 1989).

J.G. Simms, Jacobite Ireland, 1685-91 (London 1969).

J. R. Jones, The revolution of 1688 in England (London 1972).

Published by PRONI:

Ireland after the Glorious Revolution, facsimilies nos. 221-240 (1976).

Kings in Conflict: Ireland in the 1690s, educational resource pack (1990) (Published jointly with the Ulster Museum).

The Penal Laws, facsimiles nos. 101-120 (1990).

Hugh Fenning, The Fottrell Papers 1721-39 (1980).