By Robin Fuller

One hundred years ago it was quite common for Irish people to believe that they were living in times foretold by St Malachy, the twelfth-century archbishop of Armagh. Malachy purportedly predicted that, after 700 years under the yoke of her foe, Ireland’s ‘light shall burst forth as the sun’:

‘The Church of God in Ireland shall never fail! With terrible discipline long shall she be purified, but afterwards, far and wide shall her magnificence shine forth in cloudless glory. And O Ireland! Do thou lift up thy head. Thy day also shall come—a day of ages!’

Malachy was better known internationally for another prophecy, a prediction of the succession of popes, but in Irish newspapers and political conversations in the 1910s and ’20s the ‘Prophecy of Malachy’ had nothing to do with the papacy and everything to do with contemporary politics. St Malachy was a household name, and his Irish prophecy was not only widely known but also widely believed. Nationalists of all persuasions agreed that Malachy had anticipated Ireland’s twentieth-century struggle for independence. Naturally, during and just after the Civil War there was disagreement about the details. For the victors of the Civil War, the Irish Free State was Malachy’s prophecy fulfilled. A front-page poem in the Weekly Freeman in June 1922, bluntly titled ‘The Irish Free State. Saint Malachy’s Prophecy’, declared:

‘After years of persecution, after centuries of pain,

It has been foretold, O Erin! that thou wilt be free again;

When Saint Malachy had travelled far from country and from home,

To him was vouchsafed a vision of thy glorious days to come.’

It continued like that for another six stanzas.

ART O’MURNAGHAN’S ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPT

Republicans, too, the losers in the Civil War, were convinced that Malachy was on their side. In 1924 the Irish Republican Memorial Society was established to commemorate those who died for the ‘Irish nation yet unborn’, as one member called it. Their plan was to memorialise not only the dead of the 1916 Rising and the War of Independence but also those who died at the hands of the sitting Free State government during the Civil War. They hired the artist Art O’Murnaghan to create an illuminated manuscript and determined it appropriate to dedicate a page to Malachy’s prophecy.

St Malachy was of particular interest to nationalists of the Catholic ‘Irish Ireland’ kind, who envisioned a culturally independent nation built on Gaelic tradition and Catholic faith, an ideology encapsulated in D.P. Moran’s The Philosophy of Irish Ireland (1905). During the early days of Irish independence, in the pages of Moran’s newspaper, The Leader, the religious aspect of Malachy’s vision for Ireland was given as much consideration as the political. It was often impossible to distinguish between the two. ‘There is nothing now that can arrest the march of the Nation’, wrote one contributor to The Leader in 1921: ‘Pearse and Ashe, Mac Suibhne and Barry are beckoning. God is calling. Malachy’s prophecy must be fulfilled.’

For other Catholic nationalists, it wasn’t just the big picture that Malachy predicted; he could also be found in the details. Fr O’Reilly of Tang, Co. Westmeath, claimed that Malachy foresaw the Irish-language revival (‘the Irish language has come to stay, Saint Malachy’s prophecy will surely be fulfilled’), and in 1919 Cardinal Michael Logue, then holding Malachy’s old seat as archbishop of Armagh, linked the Malachy prophecy to contemporary over-taxation in a rambling speech in St Colman’s Cathedral:

‘If you had any confidence in the prophecy of my predecessor, Saint Malachy, when Ireland according to him would bloom like the Rose of Jericho, notwithstanding the efforts to keep the people down and in an inferior position, and to destroy their commerce and rob them by carrying off their taxes and shovelling out money without limit in England, and not returned to Ireland any of the thirty million a year which she now contributed to the British Exchequer!’

PROPHECY OF THE POPES

Malachy’s Prophecy of the popes was not in fact written by St Malachy in the twelfth century. It was most likely the work of Arnold Wion, a Benedictine monk who first published the text in 1595. His motivations were obscure and so was his prose, consisting of concise biographical statements about past and future popes. Owing to the Nostradamus-like vagueness of the papal prophecy and the ease with which it bends to reinterpretation, it has maintained a following among those who seek hidden knowledge, fear imminent end times or are in some other way conspiratorially inclined. Malachy foresaw the First World War, according to the occultist Ralph Shirley’s 1915 book Prophecies and omens of the Great War (third edition), and a YouTube video with over 596,000 views at the time of writing warns that ‘Saint Malachy’s Prophecy about Pope Francis is About to Happen in 2025’.

Malachy’s Irish prophecy has not maintained such a following, nor was it written by Wion, and it was far more specific in its claims about Ireland than Wion’s elliptical statements about popes. Unfortunately for the cause of Irish nationalism, it was also of dubious origin.

The story goes that Malachy died in 1148 during a visit to St Bernard at Clairvaux Abbey, in north-eastern France. That much is true, as confirmed in The life and death of Saint Malachy, written by St Bernard himself. However, the following anecdote was not recounted by Bernard. On the way to Clairvaux, Malachy rested for a night at a farm run by the abbey. That evening, as he prayed, Malachy was suddenly surrounded by light. Other monks heard Malachy calling to God, and a voice that was not his own spoke through him, pronouncing, ‘The Church of God in Ireland will never fail!’ Malachy’s prophetic words were transcribed at Clairvaux, supposedly for inclusion in Bernard’s book, although apparently they didn’t make the cut. Nevertheless, a manuscript of the prophecy eventually wound up in the archives of the Benedictine abbey of Einsiedeln, Switzerland. There, in the seventeenth century, they were read by a monk, Jean Mabillon, who then wrote about his findings to another Irish saint and sometime archbishop of Armagh, Oliver Plunkett.

All of this was forgotten and lost to history until the 1866 publication of Ireland’s destiny revealed, or the Prophecy of Saint Malachy, a 54-page pamphlet attributed to an author going only by ‘Accola’. This was most likely the pseudonym of David Power Conyngham, a Tipperary-born, New York-based journalist and author of The lives of Irish saints (1870). According to both Ireland’s destiny revealed and The lives of Irish saints, the correspondence of Mabillon and Plunkett was discovered gathering dust in the Convent of St Isidore in Rome. Malachy’s Irish prophecy gained greater popularity and credibility when it was promoted by Cardinal Patrick Francis Moran, the Carlow-born, Rome-educated archbishop of Sydney. The second edition of Cardinal Moran’s Memoir of the Venerable Oliver Plunkett (1895) featured the prophecy as well as Mabillon’s letter to Plunkett in the exact same English-language wording as found in Conyngham. The cardinal didn’t credit the New York journalist as his source, but he did suggest that he himself, as a prominent Irish cleric working in Australia, was living proof of Malachy’s prophecy fulfilled: ‘We see the prophecy most fully verified in the renewed splendour of the Irish Church and the marvellous fruits of her missionary zeal in distant lands’.

Meanwhile, back in Dublin in 1924, the Irish Republican Memorial Society, who had been inspired by Cardinal Moran’s book to include Malachy’s prophecy in their illuminated memorial to the Republican dead, were determined to inscribe the prophecy in Malachy’s own Latin words. When they were unable to locate the original manuscripts they began to doubt the veracity of the prophecy. O’Murnaghan got as far as illuminating a beautiful frame, but it was never filled with the text of Malachy’s Irish prophecy as originally intended.

MALACHY IN STAINED GLASS

Malachy remains an important saint to many Catholics in Ireland, but his prophecies, whether

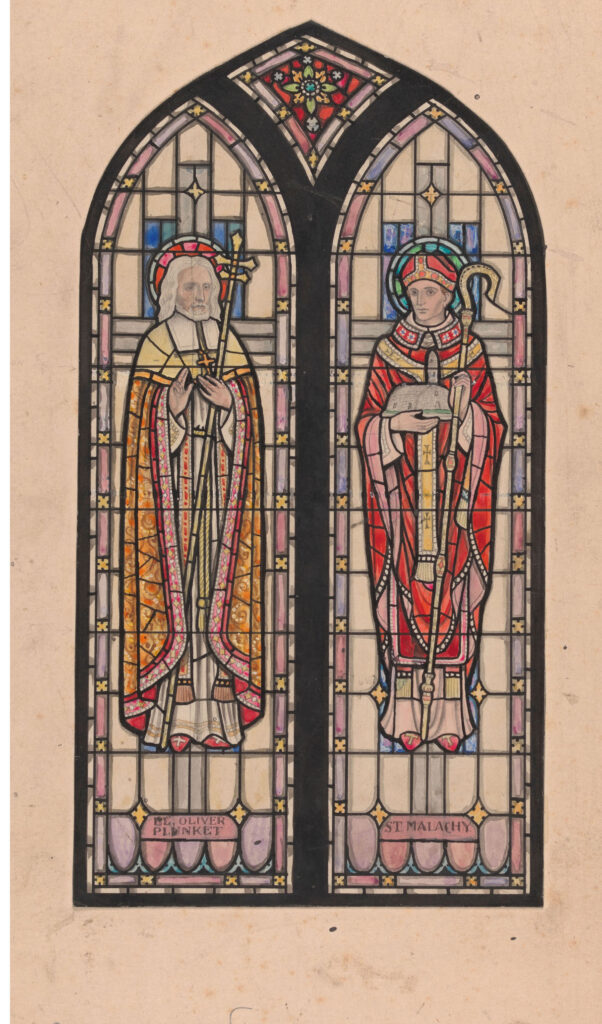

papal or Irish, are no longer common currency. Yet there are still traces of an earlier generation’s greater enthusiasm for Malachy. O’Murnaghan never completed his illuminated Malachy page, but the renowned Harry Clarke Studios created several striking stained-glass depictions of the saint in the first decades of Irish independence. In 1924 Clarke himself created a window on St Bernard for the Church of the Sacred Heart in Donnybrook, Dublin, at the foot of which he depicted the meeting of Malachy and Bernard, a scene which many at the time would have recognised and understood in terms of the popular prophecy. The following year Clarke dedicated a window to Malachy in the chapel of Belmont College, Dublin. In 1936 Richard King of Clarke Studios told several episodes of Malachy’s life in a window for the Dominican Church in Dundalk. Emulating the elongated and dream-like style of his master, King depicted Malachy performing a blessing and dying in the arms of St Bernard, but stayed away from overt references to the apocryphal prophecies. There is one later work from the Clarke Studio, by Harry’s nephew, Terrence, which perhaps alludes to the old belief in Malachy’s vision. A sketch for a dual-arched window by Terrence Clarke in the Digital Collection of Trinity College, Dublin, depicts St Malachy and St Oliver Plunkett side by side, united again as they once were in a now-forgotten myth—a fabrication which nevertheless inspired Irish nationalists to make real their own visions for an independent Ireland.

Robin Fuller is a writer and researcher based in Dublin, currently researching theosophy in the Irish Free State.

Further reading

M. Helmers & K. Rose, ‘The spirit of Ireland’s past: illumination, ornamentation, and national identity in public art’, in V. Kreilkamp (ed.), The Arts and Crafts movement: making it Irish (Chicago, 2016).

D. Power Conyngham, Lives of Irish saints (New York, 1870).

St Bernard of Clairvaux, Life and death of St Malachy of Armagh, at archive.org.