By Peter Murray

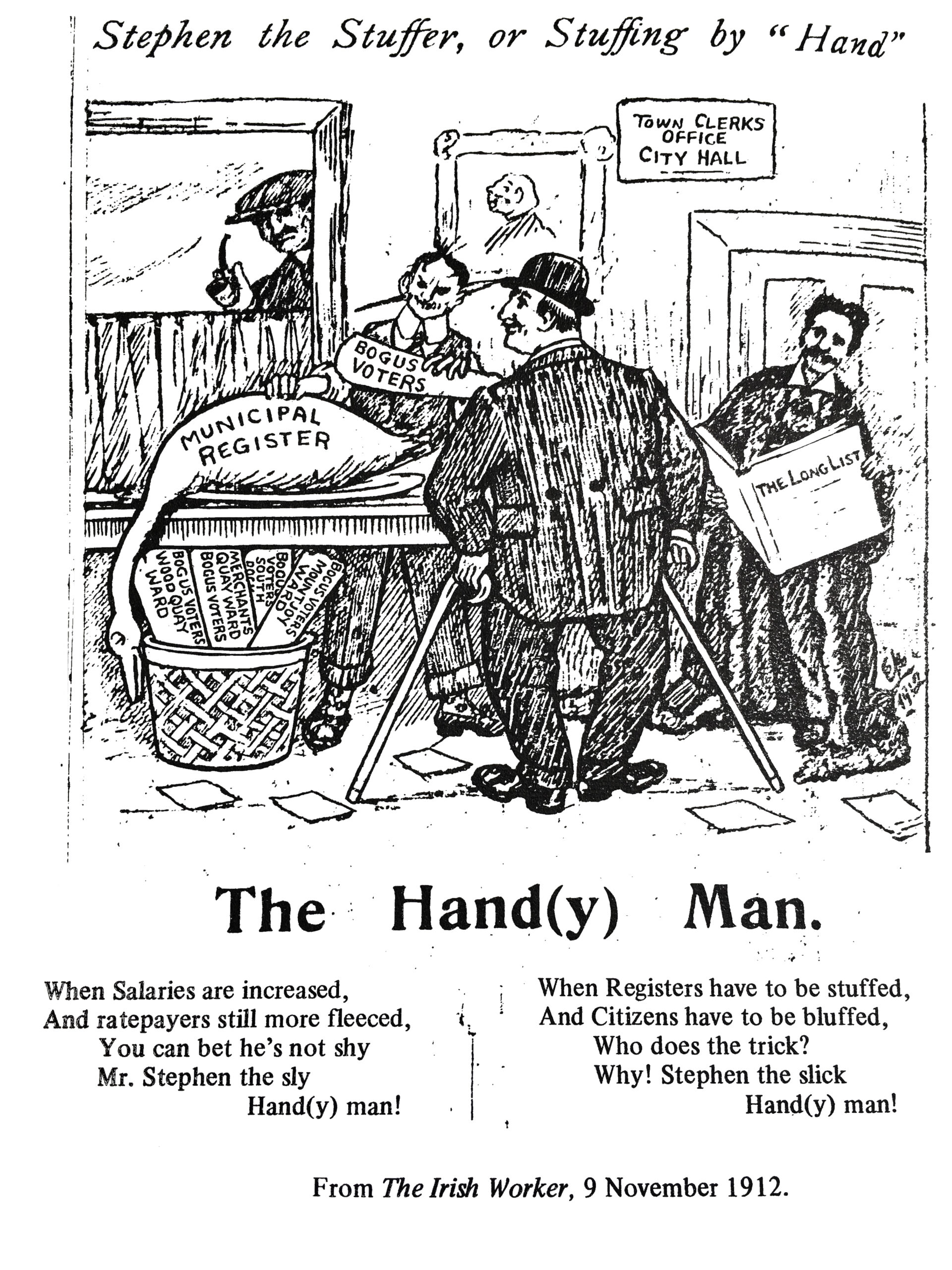

Ernest Kavanagh’s Irish Worker cartoon (below) depicts three figures—the lord mayor of Dublin, Lorcan Sherlock, on the right; Dublin’s town clerk, Henry Campbell, in the centre; and an official employed in the town clerk’s office, Stephen Hand. Two of the three—Sherlock and Campbell—are to be found in the Dictionary of Irish Biography; Stephen Hand is not, but he is clearly the cartoon’s main target. Who was he? And why did such an apparently junior official attract such negative attention?

VOTER REGISTRATION AND ‘STUFFING’

A little over a decade before the cartoon’s publication in 1912, Stephen Hand, aged 28, gives his occupation in the 1901 census as ‘registration agent’. What he registered were voters. Nowadays quite a simple process, in the early twentieth century registration of voters involved a series of stages stretched out over most of the year. In April, requisition forms were served on occupiers or landlords. In July, a ‘long list’ based on the returned forms was published. August was given over to claiming votes for those not on the list or objecting to votes being given to those included. In September, revision courts staffed by barristers began adjudicating on the claims and objections lodged. The following January the new register came into force.

This system produced an electorate that was large—in the United Kingdom the number of parliamentary votes corresponded to about 60% of the adult male population—but open to manipulation. Some of this manipulation was lawful. By managing the facility to claim and to object through their agents, the political parties sought to put their friends on the register while keeping their enemies off it. In Ireland it was easy to work out what category a person fell into. This could be accurately predicted from their religion.

Some kinds of manipulation, however, were not lawful. For instance, agents might get hold of requisition forms and insert false information. This created voters who did not exist but whose votes could be cast at election time through organised personation. Known as register ‘stuffing’, this is what the cartoon accuses Hand of indulging in, while Campbell and Sherlock connive at his malpractice.

HOME RULE/UNIONIST RIVALRY

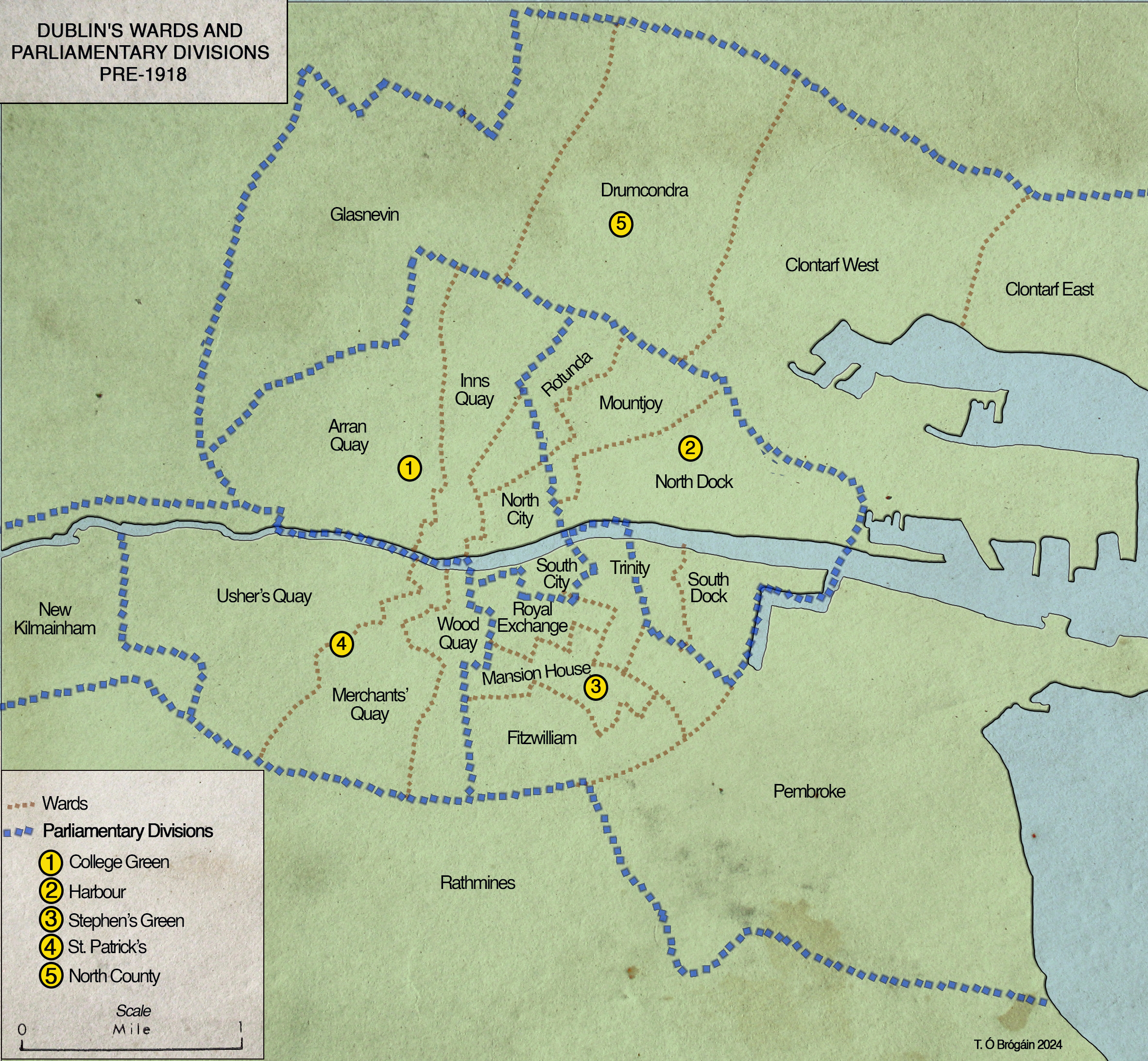

Whether it was legal or illegal, the context for register manipulation was competition between political parties. In Dublin up to 1900 this took place between Home Rulers and unionists in elections for parliament. Geographically it was concentrated in two of the six borough and county seats—St Stephen’s Green and South County. These seats comprised the south-eastern portion of the area between the canals, the adjacent suburbs of Pembroke and Rathmines, as well as the coastal suburbs further south. The rest of Dublin was safe Home Ruler territory, where the manipulative activity of agents was far less in evidence.

Around 1900 the context of party competition changed significantly. The previously restrictive municipal franchise in Dublin was broadened to the extent of the parliamentary one. In one respect it was even broader—a substantial number of women acquired a municipal vote. Over time, this facilitated nationalist challenges to the Home Rulers from their left, as first Sinn Féin and then Labour parties fought Dublin Corporation and Poor Law elections with programmes stressing the need for housing and public health reforms.

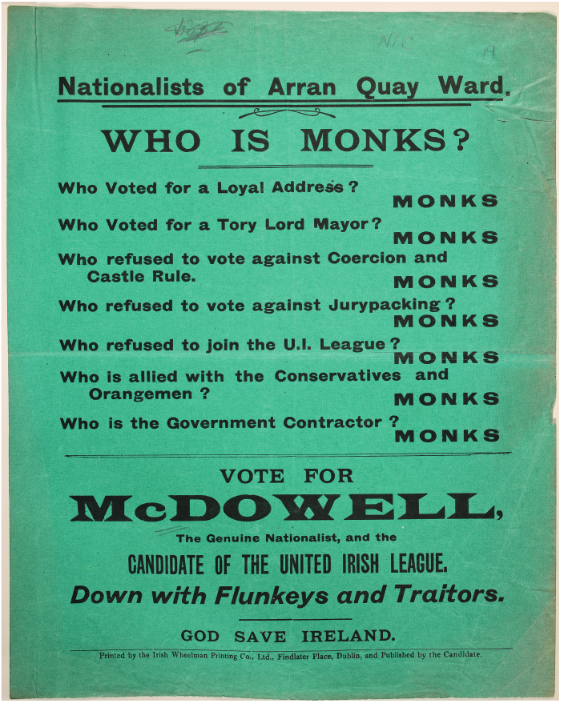

Before this trend had time to emerge, the decade-long split in the Home Rule party triggered by the O’Shea divorce case ended in February 1900. In April of that year Queen Victoria visited Ireland, and Dublin Corporation, breaking with the pre-split policy of Parnell and his party, voted to present her with a loyal address. To re-establish itself in Dublin, the reunited Home Rule party’s national organisation, the United Irish League (UIL), targeted the ‘flunkey’ members of the Corporation who had voted for the loyal address. Across the city this was largely unsuccessful—only seven of 21 surviving nationalists who voted for the address were not re-elected when their terms expired. One city ward, Arran Quay, was an exception to this pattern. Between the River Liffey and the North Circular Road, this ward stretched from Phibsborough through Grangegorman, Smithfield and Stoneybatter to Arbour Hill. All four of Arran Quay ward’s representatives supported the address. Within six years all of these had retired or been defeated after a struggle in which Stephen Hand was prominent in his capacity as UIL branch secretary.

UPSURGE IN VOTER REGISTRATION IN ARRAN QUAY

The contest between ‘flunkeys’ and the UIL in Arran Quay featured a big upsurge in voter registration activity, many disorderly public meetings thatare described in police reports and three election petitions that sought to overturn election outcomes in the courts because the winning side had employed corrupt or illegal practices to secure their victories. These Arran Quay election petitions helped to shape Hand’s public image, turning him into something more than just an energetic and resourceful operator in the revision courts.

One result of the earliest of the three election petitions was that Hand was found guilty of, and reported for, engaging in illegal spending. This meant that he incurred a penalty of seven years’ disfranchisement. Giving evidence in the following year, he made statements that would be subsequently used against him. He declared that ‘I would not stop at trifles, especially where the [UIL] would be concerned’, and admitted responsibility for recruiting the ‘straw men’ in whose names a petition was brought. Asked ‘Is it a fact that they haven’t a penny between them?’, he replied that ‘I would not give a fiver for the four of them’. The significance of this emerged shortly afterwards, when the ‘flunkey’ councillor whose election was unsuccessfully challenged was awarded his costs for a hearing that had lasted thirteen days. These costs amounted to £822-12-3. The petitioning side had been required to lodge £150 in court but, as regards the remainder, counsel stated that there was ‘little probability of recovering from the petitioners’. After 1903, ‘flunkeys’ ceased to contest Arran Quay elections and, for a decade that stretched up to the First World War, UIL candidates were returned unopposed in the ward.

SINN FÉIN AND LABOUR

While they did not encroach on Arran Quay, it was also from 1903 that first Sinn Féin and then Larkinite Labour candidates challenged the Corporation’s dominant Home Rulers in other wards that mainly formed part of Dublin’s ‘safe’ nationalist parliamentary seats. The Home Ruler response to this new competition was to stop attacking ‘flunkeys’ and start using manipulation of the voting register to push back the new challenge they faced. In 1907 Stephen Hand joined the staff of the town clerk’s office, ‘the reason given being that his salary would be counterbalanced by the saving that would be effected in consulting counsel on intricate registration cases’. Protests began immediately. According to Alderman Tom Kelly, speaking at a Corporation meeting in June 1907:

‘This was a purely partisan appointment suggested by the Town Clerk and his little coterie to pursue the Sinn Féiners… these fellows were “gabby” and had proclaimed that “they will do for the Sinn Féin men” … if these fellows wanted to injure the Sinn Féin party, they should do it at their own expense and not use the ratepayers’ money for the purpose.’

As Ernest Kavanagh’s cartoon illustrates, such Sinn Féin or Labour protests continued to be made in succeeding years.The protesters were a powerless minority, however, and it is noteworthy that Dublin’s unionists did not join in attacks on Hand’s appointment and activities. Plainly, the unionists did not see themselves as disadvantaged by his Corporation staff role. This reflected the reality that Dublin was electorally divided into two zones that overlapped with one another only to a small extent. Unionists and nationalists competed in parts of the city where for the most part Sinn Féin and Labour did not put in an appearance.

The year 1914 was a memorable one for Stephen Hand. In June, when the Irish Volunteers’ executive committee acceded to John Redmond’s demand that his nominees be added to their number, Hand was one of the ‘representative Irishmen’ on the Irish Party leader’s list. In December the Arran Quay UIL branch made a presentation to Hand and his wife, Catherine. Hand received ‘a finely illuminated address’, while Mrs Hand was presented with ‘a splendid gold bracelet’. In addition,‘there was also a well-filled purse of sovereigns’. The contributors to this testimonial included ‘the Town Clerk, Law Agent and several officers of the Corporation’.

In 1915 revision of the voters’ register and municipal election contests were suspended owing to the Great War. A parliamentary general election was due to be held but this was postponed, and the Westminster parties observed a wartime ‘truce’ that allowed the party in possession to fill vacant seats without a contested by-election. This truce only operated to a very limited extent in Ireland, initially because of a breakdown in the Home Rule party’s discipline and later because of the re-emergence of Sinn Féin in the wake of the 1916 Rising. Dublin Labour also entered the fray on one occasion, putting up a candidate at the College Green by-election in June 1915. Here Hand, in his home constituency, was to be found strongly supporting the Home Ruler, John Dillon Nugent. In the South Longford by-election of May 1917, a Sinn Féin adherent recalled the active involvement of Hand, ‘John D. Nugent’s right-hand man and a skilful manipulator where votes were concerned’.

1918 REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE ACT

Huge changes were made to the parliamentary electoral system in 1918. The Representation of the People Act increased the size of the UK electorate from 7.7 to 21.4 million, with women over 30 becoming eligible to vote. Franchise extension was accompanied by redistribution of parliamentary seats. The number of Dublin city and county seats rose from six to eleven. The Arran Quay and Glasnevin wards were combined to form the St Michan’s constituency. In December 1918 Sinn Féin won this and every other Dublin seat apart from Rathmines, where a unionist was elected.

January 1920 saw the restoration of municipal elections after a five-year hiatus. Proportional representation (PR) had replaced ‘first past the post’ as the election method. In this first large-scale outing for the new system,‘one hundred and thirty supervisors, calculators, transferring clerks, counters and sorters specially trained by Mr Stephen Hand of the Town Clerk’s Office were employed’. When their work was completed, Sinn Féin fell short of an overall majority on the new Corporation but, operating in tandem with one of the two Labour groups, it enjoyed effective control. In May the Corporation switched its allegiance from the Local Government Board (LGB) to Dáil Éireann. In November, tensions between newly elected councillors and long-serving officials came to a head when Henry Campbell disregarded an order not to hand over the Corporation’s accounts for audit to the LGB. The town clerk was dismissed without pension, as was his assistant.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOARD VS DÁIL ÉIREANN

In March 1921 Hand resigned his Corporation position and requested that body ‘to fix his superannuation allowance’, but because the Corporation left the matter in abeyance Hand, like his recently dismissed superiors, turned to the LGB for redress. With the Corporation ignoring correspondence on the matter, the LGB made pension awards to the three men and deducted their amount from grants that it was due to pay to the local authority. As the Treaty settlement emerged, the British side insisted that these pensions, and others awarded under similar circumstances, be honoured, while the Irish side protested that the amounts awarded were excessive. Eventually, arbitration was agreed upon, with the new Irish state undertaking to honour the arbitrator’s award and the British government agreeing to pay the difference in cases where the arbitrator reduced the initial award. The Free State brought the matter to a close by passing the Local Officers Compensation (War Period) Act in 1924.

In Hand’s case, the arbitrator had brought the LGB’s £491 per annum down to £355/19/6, a reduction in the Free State government’s liability of about a quarter. The verses of Ernest Kavanagh’s cartoon had charged the ‘sly Hand(y) man’ with being adept at securing salary increases from the Corporation. Financially, his retirement appears to have been a shrewdly timed move,but a generous pension was perhaps the only bright spot in the prospects facing a 50-year-old man. The Home Rule party that he had identified with and served since the turn of the century was all but obliterated. At the same time, Hand’s renowned voter registration skills were largely redundant by the end of the war thanks to the simplification of franchise qualifications and of administrative procedures.

DEATH

Stephen Hand’s story ends abruptly and unexpectedly. On 25 January 1924 the Evening Herald reported that ‘Mr Stephen Hand died at his residence, 98, N.C.R., Dublin of pneumonia following influenza’. The newspaper described him as ‘one of Dublin’s best known citizens’, while the Irish Times called him ‘a well-known official of Dublin Corporation’. For the Freeman’s Journal, ‘there were few in Dublin, if not in the whole country, who had a more expert knowledge of registration work and it was in this sphere, perhaps, that Mr Hand was best known in the city’. His funeral was private. He had been dead for six months before the pension arbitration process was completed. His old boss, the former town clerk, now Sir Henry Campbell, suffered the same fate of dying (in March) prior to the arbitrator’s arriving at a slightly larger percentage reduction in his LGB-awarded pension than that made in Stephen Hand’s case. As detailed in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, Lorcan Sherlock, the third character in Ernest Kavanagh’s cartoon, prospered in public service and business. He died in 1945.

Peter Murray is a member of the Maynooth University Social Science Institute.

Further reading

M.E. Daly, Dublin: the deposed capital (Dublin, 1984).

P. Murray, ‘Electoral politics and the Dublin working class before the First World War’, Saothar 6 (1980), 8–25.

P. Yeates, A city in turmoil: Dublin 1919–1921 (Dublin, 2012).