Strokestown Famine Museum

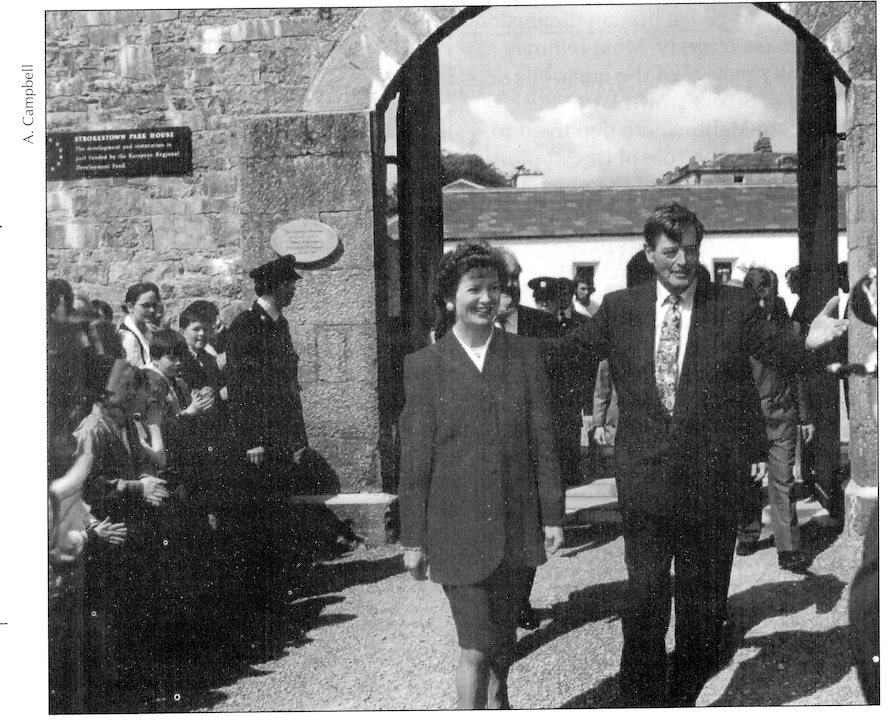

On 14 May the Famine Museum at Strokestown, County Roscommon, was opened by President Mary Robinson. This event was widely covered in the Irish and British press and was remarkable for both the President’s positive and moving speech, and the intrinsic importance of this project for understanding the Irish past and its modern legacy.

How good is it?

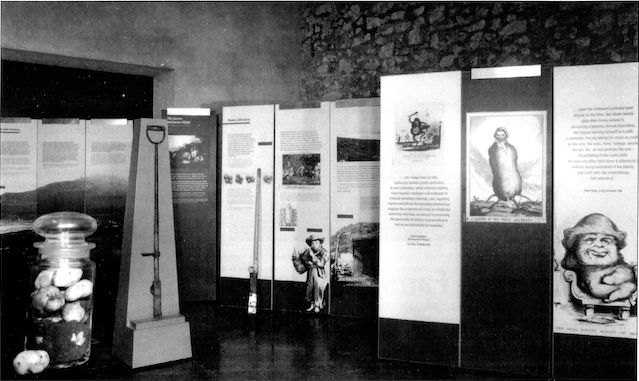

Given the claims made for it and the expectations raised, the question arises: just how good is it? A few misconceptions and concerns should first be dispelled. The museum has been described as ‘post-modern’, but this is an overstatement. While the irony of its location in the outbuildings of Strokestown’s ‘big house’ is patent, the style of the museum is sober, didactic and educational, without being oppressive. If a consistent interpretive bias is evident here, its intellectual honesty contrasts favourably with the hidden agendas or incoherencies which frequently underlay many museums’ claims to objectivity.

The arguments informing the museum are clear: the centrality of the Famine to the modern Irish historical experience; the vulnerability of the early nineteenth-century Irish economy to potato failure due to a lack of sustained development, to undercapitalisation and to an exploitative agricultural structure; the failure of the British state to respond adequately to the catastrophe, and the culpability of Irish landlords in seeking to utilise the situation for their own ends. All these reflect the dominant strands in current reassessments of Famine history, but what really gives the museum its specific character are the relentless reminders of the contemporary relevance of Ireland’s experience to the modern world. The ‘Third World’ aid agencies Oxfam, Trocaire, Concern and Afrl have all been actively involved in the development of the museum, and while exact parallels with the Irish events need to be care fully handled, their interpretive panels interspersed throughout the museum are generally effective and thought provoking. All this embodies the hope expressed by Mary Robinson that the museum encourage Irish visitors to ‘think imaginatively and link our past to the future of vulnerable peoples’.

Holocaust not ‘heritage’

This seriousness of purpose — reflecting director Luke Dodd’s choice of the Holocaust rather than the National Trust as his reference point—marks the Strokestown museum apart from many of the interpretative centres which proliferated in Ireland in recent years. At worst these can be historically bogus — almost entirely devoted to ‘heritage’-related entertainment — an obstacle rather than an aid to any serious engagement with the past. The Famine Museum uses a range of media in an intelligent and sensitive way, but with due restraint.Visitors will be challenged and provoked. While the museum is demanding, it will repay the attention invested in it. Some would predict that such a venture is doomed to fail because of its refusal to pander to a solely tourist-friendly agenda, but it is to the credit of its private backers that this path has not been followed. The success of this magazine has demonstrated that an intelligent and enthusiastic market for Irish history exists and is rapidly growing. Furthermore, the forthcoming 150th anniversary of the Famine is stimulating local historical groups into investigating the past in sophisticated ways. These trends bode well for the Strokestow. approach; we can only hope that they continue and leave the critics confounded.

Clear presentation

In terms of content the displays are well thought out and clearly presented. One particular strength comes from the integration of the local drama of the Strokestown area with the broader national picture.

Documents from the local relief com mittees and poor law union are employed to give a human dimension to the mass tragedy. Most tellingly the family papers of the erstwhile owners of Strokestown Park, the Pakenham-Mahons, are deployed to demonstrate the role of the landlords in the development of the community, and in its virtual destruction in the Famine years. Strokestown has a particular claim to host the museum, as the scene of one of the most notorious forced emigrations of the Famine years and the murder in November 1847 of the offending landlord, Major Denis Mahon. It was the most highly publicised incident of the period, and provoked a major row over alleged incitement by the local Catholic priest. When discussed in the British cabinet, attitudes ranged from calls for exemplary executions to suggestions that Mahon ‘got what he deserved’. There is a degree of poetic justice in the siting of the museum here, where the restored ‘big house’ (also open to the public) stands cheek by jowl with a reminder of its part in the decimation of the Irish people.

Some rough edges

Good as the museum is, it is not without some rough edges. Perhaps because of the speed with which the displays have been assembled, there are a number of typos. Most are minor, but several, relating to dates, could mislead less well-informed visitors. There are some more serious objections. Cartoons and other reproductions are not always fully integrated with the text and are sometimes less than relevant. Part of this problem arises from the relative dearth of illustrative material left by the social catastrophe, but occasionally misuse of material can be distracting. For example, two consecutive panels feature cartoons published twenty years apart portraying Daniel O’Connell in the form of a potato. Given the common English perception of the potato as a ‘barbarous root’, such images were of great political significance in creating a hostile view both of Irish society and its democratic mobilisation. Yet nothing in the accompanying text comments on this important connection. In addition, despite liberal use of moralistic quotations from Trevelyan and The Times to illustrate the dominant British political response to the Irish crisis, there is little attempt to explain the nature of this ideology and the reasons for its political dominance. Perhaps it is due to the deplorable state of the histori calliterature on this subject but it allows the museum texts to make such errors as repeating the charge that Lord John Russell opposed tenant right in principle.

These reservations are quibbles and are not meant to detract from the commendable achievement of Luke Dodd and his staff. The Famine Museum succeeds in its primary task, as expressed by Mary Robinson, of ‘reclaiming Ireland’s silent past’.

Peter Gray

Dublin to get Connolly memorial

A major memorial to James Connolly is to be erected in Dublin. An initia tive supported by many figures in the labour movement and in cultural cir cles has begun raising funds to have the memorial erected In Beresford Place, close to Liberty Hall. A propos al from sculptor Eamonn O’Doherty was selected in an open competition, which attracted twenty-six entries from both parts of Ireland and from Britain.

O’Doherty’s design includes a bronze figure of Connolly and a back ground of a billowing Starry Plough, also in metal. The flag, with cut-out stars and plough in low relief, will stand against the railings of the Custom House. The figure of Connolly will face across Beresford Place towards Liberty Hall. The present Liberty Hall stands close to the location of the original headquarters of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, where Connolly dis played the slogan, ‘WE SERVE NEITHER KING NOR KAISER BUT IRELAND’, and from where a detachment of the Citizens’ Army left to join the Easter Week rebels in the GPO.

A bust of James Connolly was erected six years ago in Troy, New York, where the labour activist lived during his time in the United States. A plaque marks the house in Glenalina Terrace (off the Falls Road) where he lived when he was a union organiser in Belfast. Dublin has a railway station and a hospital named after him but no memorial which might serve as a rallying point for those wishing to commemorate him. The James Connolly Memorial Initiative was established in 1992 to put that right.

Further information from, and donations to: James Connolly Memorial Initiative, Liberty Hall, Dublin

Queen Victoria faces resurrection

A proposal to raise the interred stone figure of the late Queen Victoria in UCC has raised hackles in Cork. While the college authorities want to see the queen restored to her rightful position in time for next year’s 150th anniversary, others who recall her less than generous role in Irish and world affairs are not so enthused.

The statue of the young queen, looking decidedly more handsome than in later versions, was buried in a secret ceremony in 1945. She had been dislodged somewhat unceremoniously from her plinth in the Aula Maxima eleven years earlier when relations with Britain were cool to say the least. She was first given pride of place in the former Queen’s College in 1849 and looked down on generations of Cork students before ‘people of a certain orientation’, as one senior academic put it, took her off her stand. She was replaced by St Finbarr, more politically correct at the time.

While in storage the weighty eight foot high limestone edifice made a rather undignified exit through the floorboards and a decision was taken to bury her in the college grounds.

Out of sight out of mind – until this year when the board of the college agreed to place the statue, the original College Charter with its Victorian seal, and other historic items, on display as part of an exhibition to mark the college’s 150th birth day. But then ‘people of a certain orientation’ re-emerged to object to the resurrection of a woman felt by many to be a symbol of the famine that cursed the country in the same 1840s and caused the death and emigration of millions, an event whose 150th anniversary also falls next year.

‘This woman symbolises the cruellest oppression of our people dur ing three quarters of a century of famine, of pitiless evictions and clearances. She represents too the ruthless suppression of helpless people of many lands by that repulsive caste of landlord, factory prince and military adventurer, over which she presided, and on whose enormities against hapless Irish, African, Indian, Aboriginal and Maori poor the sun never set.’ So said Crist6ir de Baroid, a republican of the old school who has been active for many years bringing cross-com munity groups of children from the North to Cork for holidays.

While not disputing the right of the college to commemorate its history by digging up the statue, he was more concerned with the motivation behind the restoration project. Was this an official blessing for revisionist historians, some of whom are sus pected to lurk in the hallowed halls of UCC? According to one member of the college board the matter is more straightforward: ‘The question we have to address is do we bury our history, do we turn the pages – or do we tear them out?’

Frank Connolly,

Sunday Business Post,

29 May 1994.

Dublin Photographic Archive

As part of its ongoing commitment to the maintenance and development of local studies collections, based in Pearse Street library, Dublin Corporation Public libraries extend an open invitation to anyone who may wish to donate photographs of relevance to Dublin, which would enhance the research value of these collections, now and in the future.

Often, it is not realised that family photos and casual snapshots may be of value in historical research, particularly if they depict people and places which have not been recorded by professional photographers or are not available in existing formal collections. Photographs tell us a great deal about the past – how people lived; what they wore; how they amused themselves and what kind of conditions they lived in. Your photos may be valuable records on the social his tory of Dublin – even including those family snapshots taken yesterday.

The Dublin Photographic Archive would welcome any contribution (new or old – prints, slides or negatives) dealing in particular with: BUILDINGS; LOCATIONS; PEOPLE; VEHICLES; STREET FURNITURE; IMPORTANT EVENTS. Items will be made available for public use after assessment and cataloguing procedures have been completed.

Corrections

One of our reviewers in the last HI, Mary Harris, was incorrectly listed as a history lecturer in Queen’s University, Belfast. In fact she lectures in the University of North London.

In H/Vol.l No.4 (Winter 1993) in the article on Caoineadh Airt Vi Laoghaire by L.M. Cullen, Colonel Daniel O’Connell (the picture on page 26) was incorrectly described in the caption as ‘the uncle of Eibhlin Dubh’. He was in fact her brother.