LIN ROSE CLARK

Lilliput Press

€18.95

ISBN 978184351-9218

REVIEWED BY

Brian Hanley

Brian Hanley is Assistant Professor of Twentieth-Century Irish History in Trinity College, Dublin.

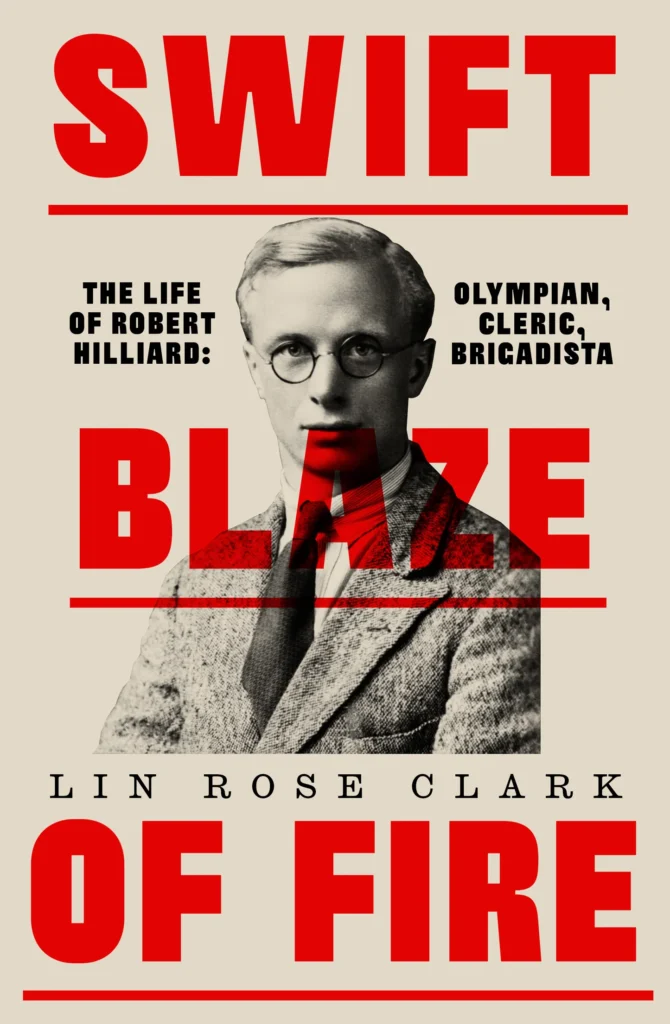

In the epilogue to this book, Lin Rose Clark tells of a postcard that her grandfather, Robert Hilliard, had sent to her grandmother, Rosemary. Hilliard had sent it from Spain, where he was serving with the International Brigades. He implored Rosemary to ‘Teach the kids to stand for democracy. Unless fascism is beaten … it means hell and war for our kids.’ Hilliard would be killed fighting at Jarama in February 1937. Only 32 years of age when he was fatally wounded, he had been a journalist, an Anglican cleric and an Olympic boxer.

Most people who have heard of him today know Hilliard as the ‘Church of Ireland pastor’ from Christy Moore’s song lauding the International Brigades. He and his comrades who fought for the Spanish Republic are honoured in Ireland with memorials, commemorative events, T-shirts and badges. In that sense Hilliard was certainly ‘on the right side of history’. In 1936, however, the Irish volunteers for the Spanish Republic were not only a small minority but also completely unrepresentative of Irish opinion. The popular mood, in nationalist Ireland at least, was pro-Franco. So Hilliard and his comrades not only rightly opposed fascism but did so in the face of intense societal disapproval. This makes their stance seem even more heroic and fits neatly with how contemporary activists like to think that they would behave in similar situations. But history is not so neat. How many political activists make decisions at least partly based on personal circumstances? The strength of Clark’s book is that she shows Hilliard to have been a complex and, indeed, flawed person. He was, she asserts, ‘no icon, either of heroism or shiftless betrayal, but a flesh and blood human being, an everyman shaped by his times, and the earlier times that gave rise to them, trying to chart a course through an extraordinary period’. In going to Spain he essentially abandoned his wife and children, including Clark’s mother Deirdre, which not only inflicted ‘great pain’ but left his wife with the ‘abiding view [that] he had never really loved her or them at all’. Clark accepts that her grandfather’s ‘readiness to fight Francoism [was] heroic’ but also asks what ‘kind of hero’ would behave in the way he often did towards those who loved him. Her attempt to piece together Hilliard’s life prior to Spain is one of the book’s strengths. She finds many assertions about him to have been false or at least unlikely, with several ‘impossibly divergent versions … filling gaps in what they knew with what they wanted to believe’. As with many activists, people have tended to read back his later stances to his earlier life, but very often there is little evidence to support some assertions. The claim by Bertie Smyllie of the Irish Times that Hilliard voted seventeen times in the June 1922 general election is almost certainly nonsense, for example.

Clark works hard to disentangle fact from fiction, but Hilliard’s life was interesting enough without any suppositions. From a comfortable middle-class Protestant background in Kerry, he grew up in a period of war and revolution. It was not always clear where he would end up. After attending Cork Grammar and then Mountjoy School in Dublin, he became a student at a still-unionist Trinity in 1921. He boxed there, to a very high standard, and represented Ireland at the 1924 Olympics. He also played hurling but was nevertheless denounced in An Phoblacht during 1926 as a representative of ‘west Britonism’. He took part in student debating societies and experimented with new ideas, but there was little sign of the communist that he would become at this point. Having dropped out of Trinity, an unsuccessful period as a journalist in London followed. This coincided with his marriage and much of this period makes for uncomfortable reading. Besides his gambling and heavy drinking, Clark reveals how cruel Hilliard could be to his wife. Indeed, an incidence of marital rape is recounted, which cast a long shadow over the relationship between Rosemary and Deirdre.

Personal redemption for Hilliard came through religion and he became an adherent of the Christian ‘Oxford Group’. This involved a ‘complete personal surrender’ to God and the embracing of what were often reactionary viewpoints. He then studied to become an Anglican priest and during 1932 began work attached to St Anne’s Cathedral in Belfast. So Hilliard’s path to communism and Spain was far from straightforward. Clark argues that, living in Belfast and London, the impact of the Depression and the rise of Nazism all profoundly affected him. Like most people, he held often-contradictory ideas, and the atmosphere of the time contributed as much to political confusion as to clarity. At times Clark is forced to make assumptions about how various events, such as the Outdoor Relief riots, the emergence of the Blueshirts or the Battle of Cable Street, affected Hilliard. This is not always as convincing as the personal narrative. It also, of course, illustrates the difficulty of rebuilding a person’s life.

Remembered by his comrades for his ‘sense of humour and consistently cheerful attitude’, Hilliard was not always an attractive personality. Clark conveys this story without romanticism, mindful of the cost to his family of Hilliard’s political choices and making us think about what becoming a ‘hero’ sometimes entails.