By Sarah Hayes-Hickey

Limerick Archives is privileged to house the remarkable collection of the Hunt de Vere family of Curragh Chase House, which contains many treasured items. During my time as an assistant archivist, I sought to familiarise myself with the collections, leading me to explore various archival boxes. One particular discovery left a lasting impression: a notebook (P22/428), ‘INVENTORY Heirlooms, Curragh Chase, Oct 1880’. The cover lists categories such as ‘Silver Plate, Plated goods, China table services, Glass, Linen, Works of Art, Furniture, China & Miscel. Ornaments’. As I leafed through its pages I was captivated. Having always been drawn to the grandeur of historic houses and the families who lived in them, I spent a fascinating hour or so immersed in the detailed entries.

The Hunt family’s connection to Ireland dates back to 1657, when Vere Hunt Esq. arrived as an officer in the Cromwellian army, settling on lands in Curragh, Co. Limerick, and Glangoole, Co. Tipperary. His descendant, Sir Vere Hunt, later represented the borough of Askeaton in the Irish parliament in 1797. Following the borough’s abolition under the Act of Union, he supported the Union and was subsequently compensated with a sinecure position as weighmaster of Cork, earning £600 per year. He also served on the grand jury of County Limerick.

A man of cultural interests, Sir Vere Hunt was passionate about literature and theatre. In his youth he managed a travelling theatre company in the south of Ireland and made efforts to establish a provincial newspaper, as well as to reprint Pacata Hibernia and other historical works. Sir Aubrey de Vere, 2nd Baronet (1788–1846), attended Harrow alongside Lord Byron and Sir Robert Peel. At just nineteen he married Mary Rice of Mount Trenchard, Co. Limerick. A supporter of Catholic Emancipation, he stood for parliament in 1820 and officially adopted the de Vere name in 1832 by royal licence, marking the beginning of a distinguished lineage at Curragh Chase—one deeply intertwined with literature, poetry and the arts. Known as an enlightened landlord, he focused on rebuilding Curragh Chase and pursuing his literary ambitions. Though he published little before the age of 30, his later works included several verse dramas, the most notable being the posthumously published Mary Tudor.

The de Vere family’s artistic and literary legacy continued with Aubrey de Vere, 3rd Baronet (1814–1902), a poet and close friend of Alfred, Lord Tennyson and of William Wordsworth, both of whom visited Curragh Chase. The estate is believed to have inspired Tennyson’s poem ‘Lady Clara Vere de Vere’.

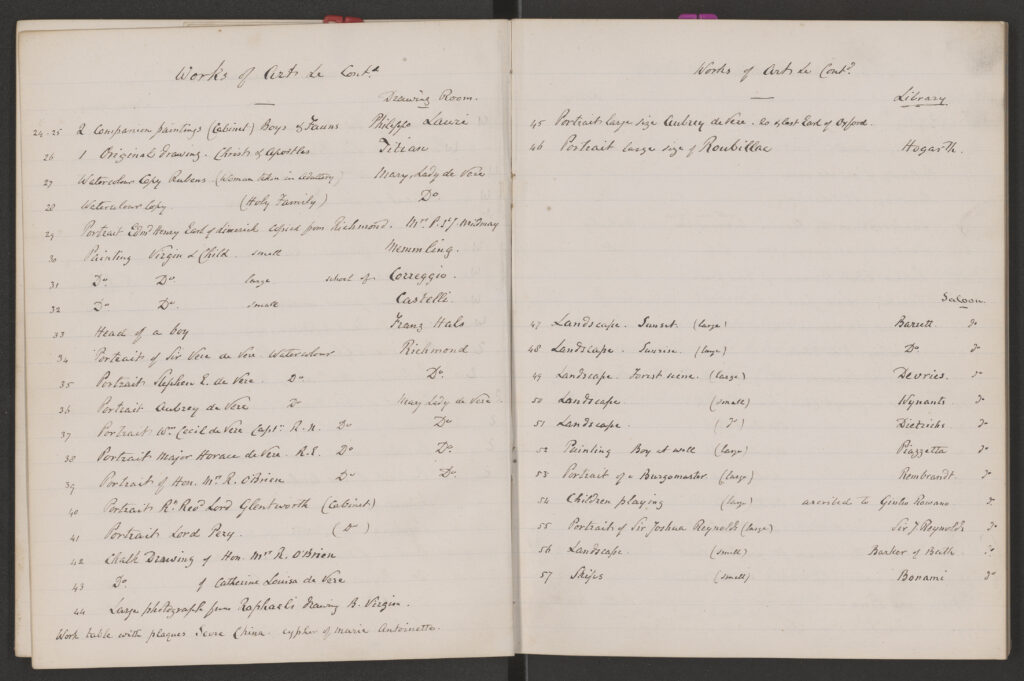

Given this rich cultural heritage, it is no surprise that the de Vere family both created and collected numerous works of art—arguably the most intriguing part of the inventory. One of the last family members to reside at Curragh Chase, Joan de Vere (1913–89), documented her memories of the house in two books, offering a room-by-room account. By cross-referencing her recollections with the inventory, we can reconstruct a vivid impression of the home’s former splendour.

Among the most valuable items listed were the ‘Colossal cast of Michael Angelo’s Moses’, a portrait of the sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac by William Hogarth, and ‘Portrait of a Burgomaster’ by Rembrandt. Joan Wynne Jones’s (née de Vere) The abiding enchantment of Curragh Chase (1983) describes the Moses statue as towering over the great entrance hall, nearly reaching the ceiling. It was said to be one of only two casts known at the time. Hogarth’s portrait of Roubiliac occupied a place of prominence above the mantelpiece in the main saloon in Joan de Vere’s time but was listed in the inventory as being in the ‘library’. The Rembrandt is listed on the inventory as being in the ‘saloon’.

The inventory also features works by world-renowned artists, such as an original drawing by Titian, the head of a boy by Frans Hals, a basso-rilievo cast by Lady Dacre and a self-portrait of Joshua Reynolds—a collection worthy of an art gallery and a source of great pride for the family.

A sense of loss lingers over these treasures, however, as many were tragically destroyed in the fire that consumed Curragh Chase House. Unlike many ‘big houses’ that were burned during the Civil War, Curragh Chase was spared, thanks to locals who vouched for the kindness of the de Vere family. Sadly, fate intervened on 21 December 1941, when an accidental fire reduced the house to ruins. At the time, the Limerick Leader vividly described the fire:

‘Rivulets of flames … aided by a strong wind quickly shot up … tongues of fire were soon licking at the roof and smoke was billowing through the windows, the whole conflagration throwing a blood-red glare across the night sky’.

Today the remains of Curragh Chase House stand as a haunting reminder of its former grandeur, overlooking the estate’s lake and picturesque grounds. Now under the care of Coillte, the tree-lined paths provide a peaceful retreat for visitors seeking solace in nature. It is an honour to serve as the guardian of the records for this cherished house and its distinguished past.

Sarah Hayes-Hickey is Limerick City and County Archivist.