By Brett Irwin

The His Majesty’s Prison (HMP) archive in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) contains many records that tell the story of the penal system of the Ulster counties that now make up Northern Ireland. These are a fascinating source for genealogists and researchers, as the general prison registers, admission/discharge registers and visitor books all have personal details, including name, address, date of birth, sentence etc. Some records remain closed to protect the identity of still-alive prisoners and family members, although researchers can apply for access under freedom of information and data protection legislation. The three main prisons of Armagh, Belfast and Derry/Londonderry feature strongly in the archive, as they are the oldest prisons in the north of Ireland and all had an aura that reflected an imposing view of state confinement. Prisons are a reflection of a time and place, and Northern Ireland has a unique story to tell. The sectarian conflict known as ‘the Troubles’ shaped not only the physical architecture of the institutions but also ideas regarding treatment and imprisonment.

There was no specific prison system in Ireland before the seventeenth century, with imprisonment being a matter for local parishes and justices of the peace. This slowly changed and by the eighteenth century every county in Ireland had a gaol for convicted criminals. These buildings typically had a simple but secure design or were guarded rooms in existing buildings. Crimes such as murder, arson, treason and highway robbery carried a death sentence, although some were commuted to transportation abroad as indentured servants, initially to North America and the Caribbean, then later to Australia. Here we can see the beginning of a prison structure that has evolved through social changes and has taken distinctive forms not only in its architecture but also in its purpose.

‘THE CRUM’

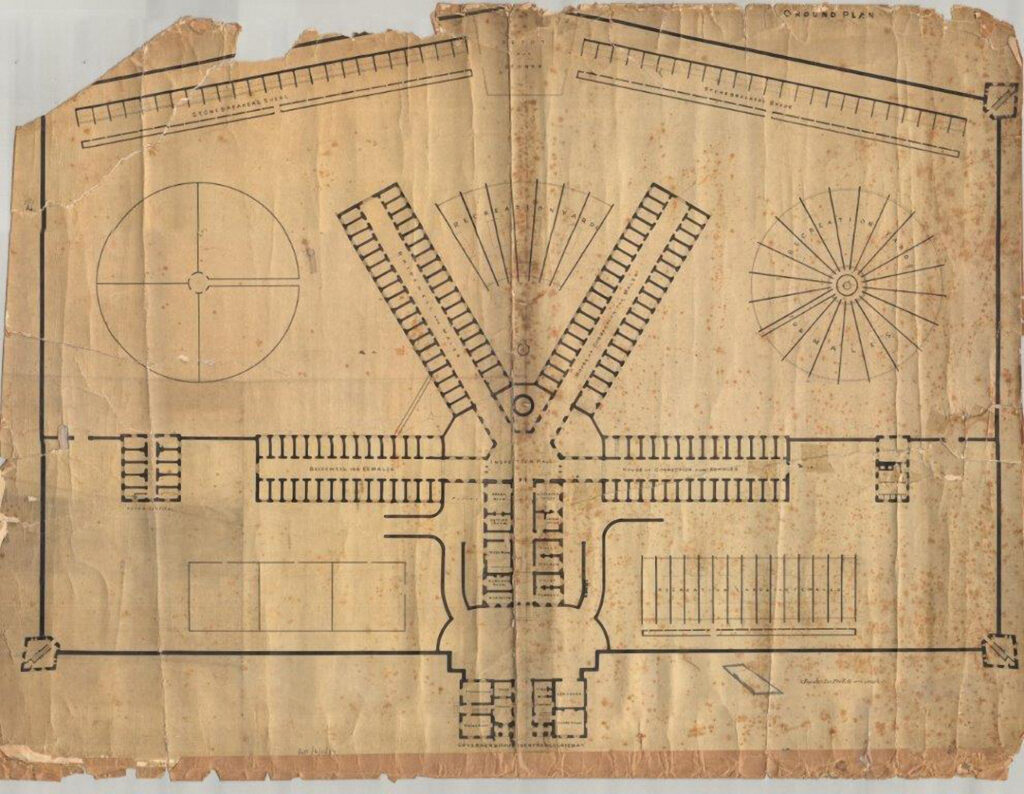

In 1845 a new prison for County Antrim was built in Belfast to replace the old gaol at Carrickfergus. The first 106 prisoners had to walk in procession from Carrickfergus to Belfast, a total distance of twelve miles. Designed by the prominent architect Sir Charles Lanyon at a cost of £40,000, the Crumlin Road Gaol was known colloquially as ‘the Crum’. Its layout was heavily influenced by HMP Pentonville in London (considered the most advanced prison design of the day). The site of the gaol covered an area of thirteen acres in north Belfast and it was divided into four separate wings—A (110 cells), B (70 cells), C (70 cells) and D (130 cells). Its design fully embodied Victorian attitudes towards penal servitude, punishment and morality. Each wing was a self-contained unit and could hold distinct categories of prisoner. Each individual cell had roughly the same dimensions—12ft long, 7ft wide and 10ft high. The prison could accommodate almost 400 inmates in single cells, although up to four prisoners per cell could be accommodated if required. As can be seen in the plan (above/below), the prison employed the Panopticon design—an institutional building with a system of control built into it whereby the prisoners could never be sure whether they were being watched all the time. The architecture has a physical as well as a psychological impact on the inmates.

There have been seventeen executions at Crumlin Road Gaol. The first, for the murder of a soldier named Corporal Brown, took place on 21 June 1854, when a fellow soldier, Robert O’Neill, was hanged for the crime. Thomas Joseph Williams was convicted for his part in the murder of a police constable and was hanged on 2 September 1942 by Albert Pierrepoint. Pierrepoint would later go on to hang an estimated 200 Nazi war criminals at the Nuremberg trials in Germany. The final execution at the gaol was for the murder of Pearl Gamble, for which crime Andrew McGladdery was hanged on 20 December 1961.

There have been several unauthorised departures from ‘the Crum’, with 37 prisoners having escaped. In a particularly large break in 1971 thirteen prisoners cleared the walls. Not every jailbreak was successful, however: in 1957 an attempt was foiled by vigilant prison officers when a tunnel was discovered leading away from C wing. Crumlin Road Gaol’s imposing iron gates swung shut for the final time in 1996. It is now a heritage site.

DERRY’S FOUR GAOLS

The Derry/Londonderry gaol had a certain notoriety owing to the imprisonment of IRA members during the Irish Civil War and for the multiple executions that took place. The first gaol was built in 1620 and stood on the corner of Butcher Street and the Diamond. The second version was constructed over Ferryquay Gate in 1676 and lasted for around 120 years. In 1791 a new gaol opened in Bishop Street. In 1798 a certain Theobald Wolfe Tone was imprisoned there in the aftermath of the rebellion of the United Irishmen before being moved to Dublin, where he died in custody in the same year. On the same site in Bishop Street, construction began on a fourth gaol in 1819 and was completed in 1824. The building was three storeys high and the hard grey granite of the Dungiven stone used in its construction gave it a dramatic and formidable appearance. The two large round towers, the smaller turreted towers and the turreted arch at the gate all evince an architectural style that can only be described as medieval/Victorian/Gothic. All wings joined together to form a loose horseshoe design, with the governor’s residence and chapel surrounded by a gallery that adhered to the design principles of the Panopticon. The prison had 179 cells. It was also used to hold prisoners who had been deemed criminally insane and ‘lunatic’. Between the early 1930s and 1945 these prisoners were held in custody by appointed ‘criminal lunatic’ asylum officers. Derry Gaol held a number of executions and prisoners had to await their fate in the condemned cell in the middle level of the prison. The last person to be hanged there was a William Rooney, found guilty of murder in 1923.

ARMAGH GAOL

Armagh Gaol (above/below) first opened in 1780 at the south end of the Mall in the centre of the city. It initially had eighteen cells and was designed by Francis Johnston, an Irish architect who is also notable for designing the General Post Office in the centre of Dublin. Johnston’s design for Armagh Gaol is interesting; he included three floors in the Georgian style, with two original wings at the rear of the main administration building built at right angles to each other. By 1823 the gaol held 40 prisoners, and the building was expanded in the 1840s. Armagh is often thought of as a women’s prison but it was originally mixed. After the partition of Ireland in 1921, it was reserved for female remand and sentenced prisoners, although few female prisoners were interned there during the period of the Irish Civil War. This changed during the Second World War; increased IRA activity in Northern Ireland led to females being interned in Armagh and males in Derry and Belfast. During the Troubles, the predominantly Republican female prisoners were organised along military lines with a strict code of conduct. They were continually active in political protests, particularly regarding the right to wear plain clothes rather than a prison uniform, in parallel with their male Republican comrades in Belfast and the Maze.

PRISON SHIPS

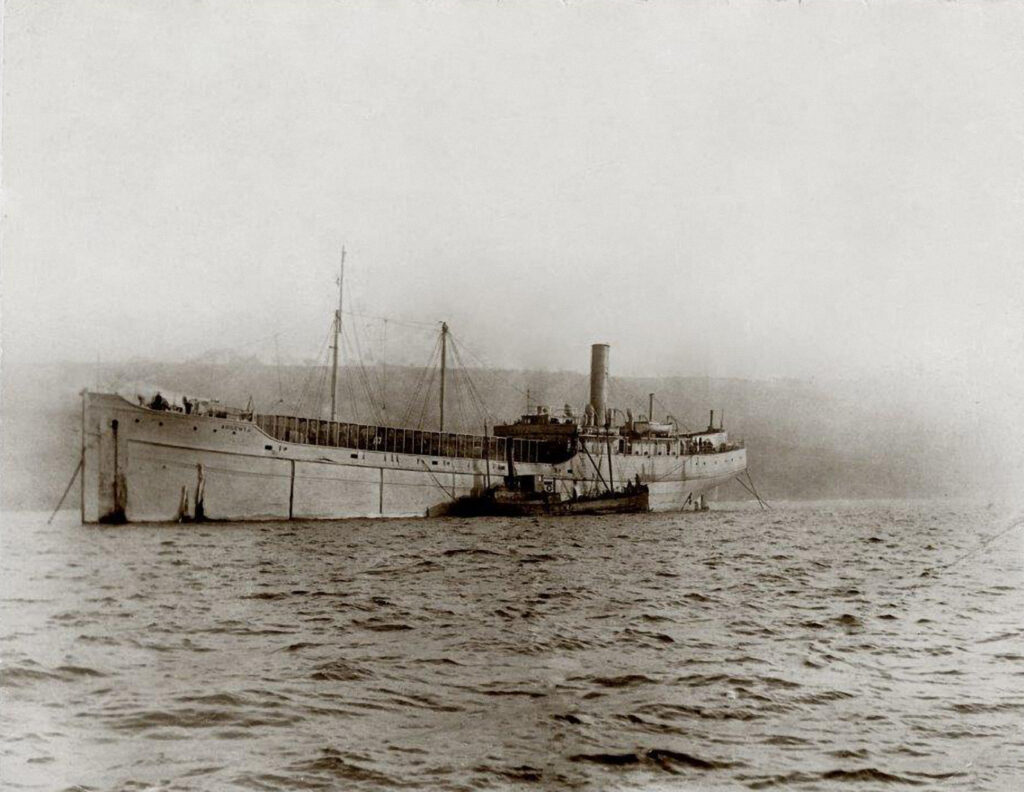

The architecture of prisons in Ireland had evolved, as we have seen, from small, secure buildings to grand, imposing Victorian structures with a massive architectural presence on the local landscape. The idea of a prison being built firmly on foundations was challenged by the use of prison ships in the north of Ireland, and later in Northern Ireland, from the 1790s to the 1970s. The use of ships as prisons was always a response to emergencies, from the rebellion of the United Irishmen in 1798 to the insurgency and subsequent internments during Operation Demetrius in 1971. In a fascinating document (D273/13) we have a list of the names of 56 prisoners on board HMS Postlethwaite, moored in Belfast Lough. The Postlethwaite was an emergency measure used in response to the crisis in Ireland in 1798. The document dates from July 1799; as the rebellion officially ended in September 1798, one can only imagine the conditions on the ship for prisoners who had already been on board for several months.

LONG KESH AND THE MAZE

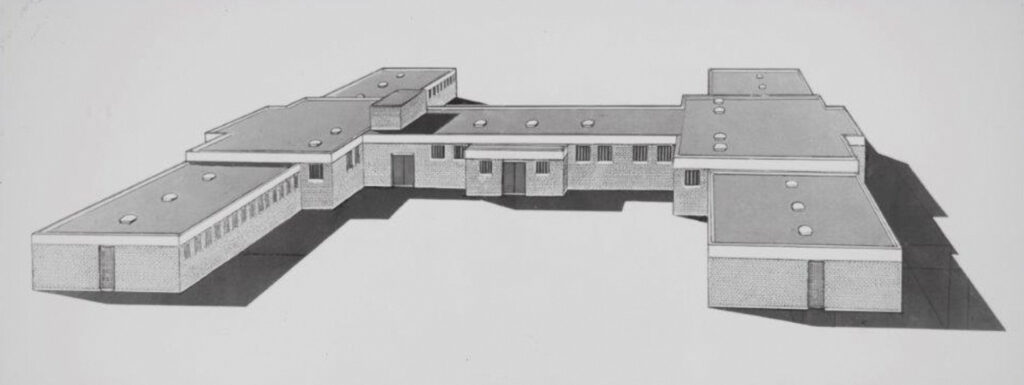

Originally an airfield during the Second World War, HMP Long Kesh (later to operate alongside HMP Maze) was built in 1970. As the violence in Northern Ireland increased in 1971, the prison became a place of internment to detain those suspected of violent, politically motivated activity. Republican and Loyalist detainees were held in 22 compounds formed of Nissan huts plus ancillary buildings. Each compound had its own commanding officer (OC) who coordinated daily routines, which included military drills and political training. The political situation in Northern Ireland deteriorated to the extent that by 1973 there were over 2,000 inmates who were classified as having ‘special category status’, meaning that they were regarded by the authorities as terrorist political prisoners. They were segregated according to their paramilitary affiliations, with groups such as the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) and the Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) represented. The antiquated system in Long Kesh needed a more secure update as political tensions intensified within the prison. In 1978 the ultra-modern cellular system of HMP Maze was initially opened alongside HMP Long Kesh during three construction phases and finally completed in 1979. This futuristic design was built as a ‘H’ shape, comprising eight massive accommodation blocks. Each block had four wings of cells and an administrative block that formed the middle section of the ‘H’. The ‘H–Blocks’, as they became known, were an integral part of the story of the Troubles. The two prisons operated alongside each other from the opening of the Maze until the compounds of Long Kesh were closed in 1987. This prison design was regarded as providing the most modern maximum security at that time and as being escape-proof—which, as we will see, was not the case.

In 1983 the attention of the global media was on the Maze, as a mass escape occurred in the supposedly escape-proof maximum-security prison. In the biggest jailbreak in UK history, 38 IRA prisoners escaped from H-Block 7. One prison officer died during the escape and twenty other officers were injured. Although nineteen prisoners were initially recaptured, the others got away and went on the run. The Maze escape of 1983 was a major propaganda victory for the IRA. The blame for the failure was placed firmly on the prison staff in the official inquiry into the breakout. (On a personal note, the author in 1983 was a teenager living in Lisburn, about three miles away. At the time of the escape, I can remember the palpable fear and tension as residents were told to check their gardens and sheds in case any escaped prisoners might be hiding there.)

PRISON MEMORY ARCHIVE

Prison archives entered the digital age when in 2006–7 former prisoners, prison officers and people involved with the education, welfare and probation in the penal system in Northern Ireland all came together to recount their experiences and personal memories for a project that became known as the Prison Memory Archive. These digital audio and film files recall aspects of prison life during the Troubles in HMP Armagh, HMP Long Kesh and HMP Maze. Many of these testimonies contain deeply personal accounts of the conflict and offer different narratives and contexts. This project, known as the Visual Voices of the Prison Memories Archive (PMA), developed into a partnership between the PMA Management Group, Queen’s University Belfast and the PRONI. To date, 157 recordings have been passed to the PRONI, where they have been catalogued and are available on site for consultation, with the archive reference number D4616. They are not available online. Records relating to Armagh Gaol are held with the classification HMP/1, Belfast prison HMP/2 and Derry/Londonderry prison HMP/3. For more information on prison records in the PRONI contact access@communities-ni.gov.uk.

Brett Irwin is an archivist in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI).

Further reading

R. Evans, The fabrication of virtue: prison architecture, 1750–1840 (Cambridge, 1982).

W.J. Forsythe, The reform of prisoners, 1830–1900 (New York, 1987).

D. Garland, Punishment and welfare: a history of penal strategies (Aldershot, 1985).

C. Ryder, Inside the Maze: the untold story of the Northern Ireland Prison Service (Malton, 2000).