By Damien McLellan

In the second episode of the recent RTÉ TV documentary Invasion: The Normans (reviewed in HI 32.5, Sept./Oct. 2024), the romantic and anachronistic 1864 illustration by James Doyle (below) was shown to represent Henry II’s arrival in Waterford. Henry is depicted as having presumably stepped up from his ship, which is lying snugly beside a substantial quay, complete with bollard and securing ring. But the same programme also used the very dramatic 1910 painting by Charles Dixon of William the Conqueror’s landing at Hastings to give a sense of his great-grandson’s landing at Waterford Harbour on 17 October 1171. This was Ireland’s 1066 and must have been equally dramatic, historic and epic, but without a turbulent English Channel in the background.

FIRST KING OF ENGLAND IN IRELAND

This was also the first time a king of England had set foot in Ireland. But which was it—jumping energetically from a beaching craft (Henry was an active 41-year-old) or stepping daintily onto a red carpet? I want to offer a more realistic and historically accurate explanation and also enable the present-day visitor to Waterford Harbour to follow the king’s journey. According to G.H. Orpen, Henry waited for over a week in Pembroke, Wales, for the weather to improve. He had sent an advance party ahead to prepare for his arrival. He was bringing ‘five hundred knights and their esquires, and a large body of archers, about 4,000 in all. A fleet of 400 ships was required to transport the men with their horses, arms and provisions.’ Quays as we know them would not materialise in Waterford until the early part of the eighteenth century. Even then ships would mostly anchor downriver, with their cargo taken to the city by lighter boats, helped by oars and small sails.

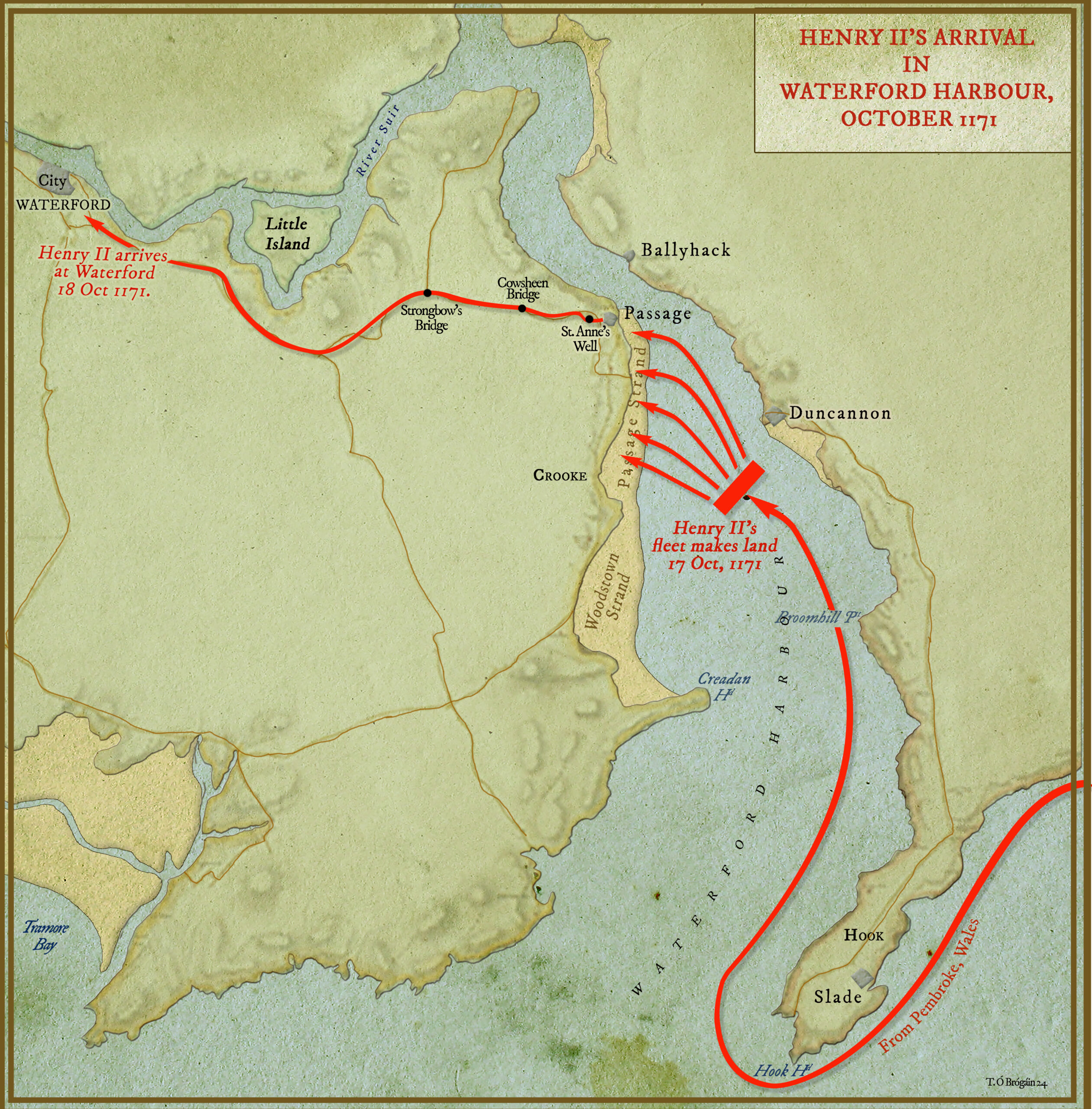

As Henry’s fleet entered the mouth of the Waterford estuary, it would have needed to follow the deep water on the Wexford side before crossing to the Waterford side. On that shore would have been the sheer cliffs of Dunmore East and Creaden Head, giving way to the exposed and unreliable sands of Woodstown Bay. It is very likely that beacons and bonfires would have been lit by the advance party to indicate the beginning and the extent of the safe landing-place, with acknowledging signals, perhaps using torches, sent by the leading ships.

PASSAGE STRAND

The earliest and most practical place to begin landing safely, I believe, would have been below the cliffs at Crooke, from which a safe beach, composed of gravel and sand, as it still is today, extends for a mile and a half to Passage East. Orpen wrote that Henry ‘landed at Crook, near Waterford, the exact landing place being probably the ferry point now called Passage about a mile from the old church of Crooke and five miles from Waterford’. I wonder did he ever visit the site? This confusing explanation has possibly contributed to some continuing to claim that Henry landed at Crooke, others at Passage. But it was surely only the entire beach between Crooke and Passage, mapped and known locally as Passage Strand, that could accommodate a fleet of 400 ships.

At the last moment the ships would lower sails and raise oars and be driven by the remaining momentum onto the beach, striving to avoid collisions, and leaving enough room to unload horses, supplies and all the impedimenta of medieval war. The landing would have been carefully timed to occur at high water so that the ships could be brought up as far as possible on the beach, leaving them secure and grounded as the tide ebbed.

Imagine the scene later that day, the ships propped and secured, stretched along Passage Strand between Crooke and Passage, nearly a mile and a half of ships. Standing on the breakwater at Passage today it is easy to see that here was the mustering area, as only here does the Strand give easy access to level land. The community centre and children’s playground perhaps stand now where the royal tent was pitched and where probably one of the most powerful men in the known world at the time had his first night’s sleep in Ireland.

THE ROUTE FROM PASSAGE TO WATERFORD

It is very likely that some ships carrying the king’s pavilion, cooks and servants would have continued up to the city, where on the following day, St Luke’s Day, Henry would receive oaths of submission and loyalty from the Earl of Pembroke (Strongbow), the Irish chieftains, the church leaders and significant others. For security reasons alone, I am assuming that it needed to be in his space and serving his food and his wine. It needed to be an impressive and overwhelming spectacle, a medieval equivalent of ‘shock and awe’.

Patrick C. Power also wondered whether

‘… the people of Waterford and especially the merchants may have heard how a great war-king travelled and equipped his army and retainers and here in front of their very eyes was a great display of wealth and power on the road from Passage to the city of Waterford the like of which had never been seen’.

The present main road through Passage is relatively modern and the only other route up from the village is impassable today. After much walking and listening to local people, however, I now believe that the historic route of Henry from Passage to the city is up a village street called the Brookside. This becomes the Wet Hill at St Anne’s Well, reaching the present main road via an existing drove road at Brook Villa, now an abandoned farm. It then continues into the city via Cowsheen Bridge and Strongbow’s Bridge. Strongbow had been this way before, on 23 August 1170, and Richard II would make the same journey on 2 October 1394. They would have known the strategic and maritime importance of Passage Strand, although its historical importance and name may have since been overlooked.

My contention is that Henry II’s fleet landed in Waterford Harbour at Passage Strand, beginning at Crooke and all along the beach to Passage, on 17 October 1171, and that Henry arrived the next day in Waterford City on horseback at the head of 500 knights, supported by a large body of archers and foot soldiers, c. 4,000 in all, a formidable force brought to intimidate and complete the Norman conquest of Ireland.

‘BY HOOK OR BY CROOKE’

In Passage today there is ample parking and a café near the village playground and community centre from where all of the above can be explored and Passage Strand walked. The ferry to Ballyhack in Wexford, which Henry II gave rights to the Knights Templar to operate, as penance for his role in the murder of Thomas Becket, still runs. For a €2 return walk-on fare (free for pensioners) you can enjoy panoramic views downriver to Hook Head and the entrance to Waterford Harbour. But be warned: as a visitor you may be told that the phrase ‘By Hook or by Crooke’ was coined by Oliver Cromwell to express his determination to take the city of Waterford. Rooting out this myth is like pulling ragwort from a dry field! But here goes: Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1990 edition) proposes that ‘It probably derives from an old manorial (Norman) custom which authorised tenants to take as much firewood as could be reached down by a shepherd’s crook and cut down with a bill-hook’. It evolved over the centuries as a phrase to mean ‘one way or another’, as used by Edmjnd Spencer in the Faerie Queen: ‘In hope her to attaine by hooke or by crooke’. That was first published in 1590, nearly ten years before Cromwell was born. Of course, in a light-hearted moment he may have used the phrase as an ironic joke, but somehow I doubt it.

EPILOGUE

Henry II’s principal biographer, W.L. Warren, concluded that Henry’s mission to Ireland was an overall failure. He may have avoided excommunication and a futile and very expensive crusade to the Holy Land that were the threatened punishments for his role in the murder of his former friend and latter enemy Thomas Becket. He prevented Strongbow and other powerful but rogue Normans setting up a rival and troublesome neighbouring kingdom. He held onto his throne despite the scheming of his powerful and well-connected wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and his power-hungry squabbling sons. But his ambition to have an obedient and peaceful Ireland, unlike a fractious and threatening Scotland, failed. Despite the enormous heavily armed force that he brought, he left Ireland without a single casualty being recorded. He didn’t carry out the pope’s bidding and bring the Irish church and monasteries under the control of Canterbury. He left the Brehon Laws in place and ordered (albeit never implemented) the safe return of the Irish displaced by the Normans. Warren puts this benign policy down to his lack of interest in Ireland and his need to bestow his attention elsewhere. This relatively benign treatment of Ireland probably explains why I find myself referring to him as Henry, something I could never do regarding Henry VIII, for example.

Damien McLellan is a consultant psychotherapist and lives in Waterford. He is grateful for the assistance from local historians, Breda Murphy and Andrew Doherty.

Further reading

G.H. Orpen, Ireland under the Normans (Oxford, 1911).

P.C. Power, History of Waterford City and County (Cork, 1990).

W.L. Warren, Henry II (New York and London, 2000).