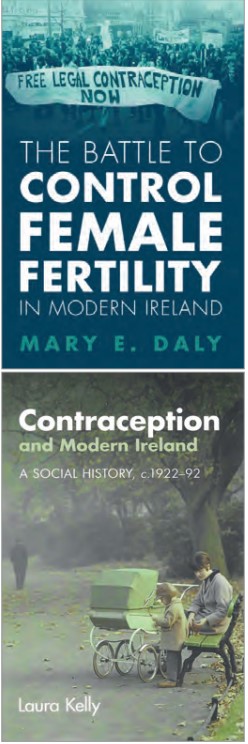

THE BATTLE TO CONTROL FEMALE FERTILITY IN MODERN IRELAND

MARY E. DALY

Cambridge University Press

£25.99

ISBN 9781009314879

CONTRACEPTION AND MODERN IRELAND: A SOCIAL HISTORY, c. 1922–92

LAURA KELLY

Cambridge University Press

£22.99

ISBN 9781108839105

Reviewed by Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny is the author of The way we were: Catholic Ireland since 1922 (Veritas, 2022).

It’s important to put social change into its historical context, and Mary E. Daly does that lucidly at the start of her authoritative account of contraception in modern Ireland (up to the 1990s). Questions like fertility were interwoven with national identity and, in effect, a national faith. Irish priests were not an élite—they were, as G.B. Shaw had observed, ‘the people’. Fertility was welcomed by an agricultural society, and farmers continued to hold anti-contraceptive views longer than other cohorts. Children could be an asset, even from a utilitarian viewpoint; the offspring who emigrated supported whole communities with their remittances.

Contraception was opposed in other legislatures too, especially during the 1930s; it was sometimes described as ‘race suicide’ as birth rates fell all over Europe. The Irish Free State prohibited birth-control artefacts in 1935, and it wasn’t alone in doing so—France, Belgium, Portugal and several American states also banned contraceptives, although the law wasn’t always enforced in practice. The most usual Irish way of controlling fertility was by delaying (or even rebuffing) marriage.

As economic and social circumstances altered, attitudes to birth control began to change. After the Second World War, however, neutral Ireland was out of kilter with neighbouring cultures: there was a baby boom elsewhere (globally my generation, born in the 1940s, are called ‘boomers’) but not in Ireland, where there was still a baby shortage. By the 1950s, with drastic population decline, sociologists were predicting that the Irish might disappear altogether. In such circumstances, campaigns to limit births tend not to be popular—although there were always women (and men) who did not want any more children and contrived to limit their families.

With the dawn of the 1960s the social context changed again: the economy began to flourish, the population decline was halted and, crucially, with the launch of the contraceptive Pill in 1961 birth control became a popular focus of media discussion. There was worldwide mounting anxiety about ‘over-population’, often focusing on the increase in people of colour (the birth-controllers Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger, too, had always sought to reduce births among non-whites). Again, however, Ireland’s evolution was slower, and a long battle for contraceptive rights was fought throughout the 1960s—the discussion around the papal bull Humanae vitae in 1968 arguably amplified, even advertised, the convenience of the Pill. The Pill, a medication, also involved doctors more seriously in women’s reproductive health: previously, the medical profession had regarded ‘rubber goods’ (as barrier methods were named) as beneath them.

In the present discourse about ‘gender’, however, nothing illuminates biology more saliently than human reproduction. Daly notes that there has been a ‘gendered’ approach to sterilisation (never prohibited), but then male sterilisation is surgically simple—the ‘snip’—whereas female sterilisation involves an operation on the internal organs.

The prompting for change often came from women themselves, and the most compelling aspect of Laura Kelly’s densely researched book is the voices of the women interviewed, highlighting their reproductive history. In one instance, the mother of a large family of twelve boys and two girls speaks of also losing three babies in one year: she had kidney disease and pregnancy was a health hazard. The need for birth regulation for women’s health could hardly be more strongly stated. And yet this whole subject contains complexities and paradoxes, too; many an unwelcome pregnancy has produced an adored child. There was not only acceptance of children but also pride in having a family.

Kelly charts some of the same territory as Daly, exploring aspects of sex education and uncovering Irish letters sent to Marie Stopes, requesting birth-control information, as well as to Angela Macnamara. The popular women’s magazines Woman’s Way and Woman’s Choice played a key role, from the 1960s onwards, in discussing issues around reproduction—and were probably freer to do so, as magazines were less scrutinised than the mainstream media. By 1977, as Eimer Philbin Bowman’s research has shown, women—including single women—were availing of birth-control support through the Irish Family Planning Association.

The Catholic Church, as we know, opposed contraception, but Kelly finds that Irish priests serving in Britain tended to be more flexible—Father Paddy Gleeson, an emigrant chaplain in Luton, had a more compassionately liberal approach, for example.

Both authors take a somewhat dismissive view of conservative opposition to the onward march of contraception and other aspects of the liberal agenda: the Irish Family League represented the dark force of reaction and ‘moral panic’. It did, however, have a constituency—until well into the 1980s most Irish people had socially conservative values. John O’Reilly’s publication Response recorded, quarter by quarter, the increase in abortion, sexually transmitted disease, divorce, homosexual rights and single parenting, and I suspect that some ultra-conservatives would suggest that their pessimism was justified: abortion has risen startlingly, everywhere, since it was legalised—despite contraception—and marriage has drastically declined. Contraception was essential to women’s health and well-being, but conservatives were not wrong in sensing that it would change all the rules.

Anyone involved in this field will benefit from both of these books, but future scholars who take the narrative up to the 2020s will face a very different picture, to include a global fertility crisis, IVF, surrogacy, transplanted wombs and, quite possibly, foetal life grown in a laboratory.