By Ivan Gibbons

On 18 December 1924 the Fermanagh Impartial Reporter and Farmers’ Journal reported that

‘The Members [of the Boundary Commission] during the morning journeyed to Garrison through Derrygonnelly, over Knockmore mountain.

The effort called for some athletic prowess, and Mr Fisher [Northern Ireland Commissioner] was forced to abandon the enterprise when about half-way up. “This is rough country”, he observed as he was almost ankle deep in water trudging back to the road.

Meantime Judge Feetham [Chairman of the Commission] had easily established himself as the best athlete in the Boundary party, with Mr Bourdillon [Commission secretary] second and Dr MacNeill [Irish Free State Commissioner] a fair third.

The Judge jumped with freedom over several water ditches and bog holes, and Dr MacNeill, although several years his senior and handicapped with goloshes, acquitted himself very well.’

Why were a group of late middle-aged and elderly gentlemen clambering over the mountains of south-west Ulster in the depths of winter in 1924? It was because all the parties involved in the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty had abdicated responsibility for deciding on the final outstanding element of the Treaty—the delineation of the border line between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. The Sinn Féin plenipotentiaries during the Treaty negotiations essentially abandoned their position when they failed to seek clarification and guarantees on what the Boundary Commission’s role and remit was to be. Both the Sinn Féin delegates in 1921 and subsequently the new Free State government from 1922 to 1924 passively accepted that the British government could appoint the pivotal role of chairman and failed to demand that Dublin be consulted about the appointment. Northern Ireland point-blank refused to recognise the Boundary Commission at all; it failed to appoint its own commissioner. As for the British, Lloyd George in 1921 saw the proposed Boundary Commission as a device to break the impasse in the Treaty negotiations without undermining Northern Ireland in the eyes of his Tory cabinet colleagues; moreover, his successors, both Conservative and Labour, once Ireland was off the British political agenda, were determined in the new post-war era of class politics to prevent the return of what they regarded as the emotive and irrational politics of Ireland to the British parliament. That is why these gentlemen found themselves marooned up the mountains of Ulster on a cold December day in 1924.

CHAIRMAN RICHARD FEETHAM

This evocative vignette succinctly illustrates the nature and characteristics of the Irish Boundary Commission so vigorously led by its chairman, Richard Feetham. Feetham was not content to amass multiplying submissions from representatives across the political divide in border areas. He believed in seeing for himself, often taking part in discussions with local inhabitants on the sectarian, and therefore political, composition of individual townlands. For the Commission the issue was black and white, as it was for the entire population in Northern Ireland a century ago—all Protestants were unionists and all Catholics were nationalists. There was no leeway on either side.

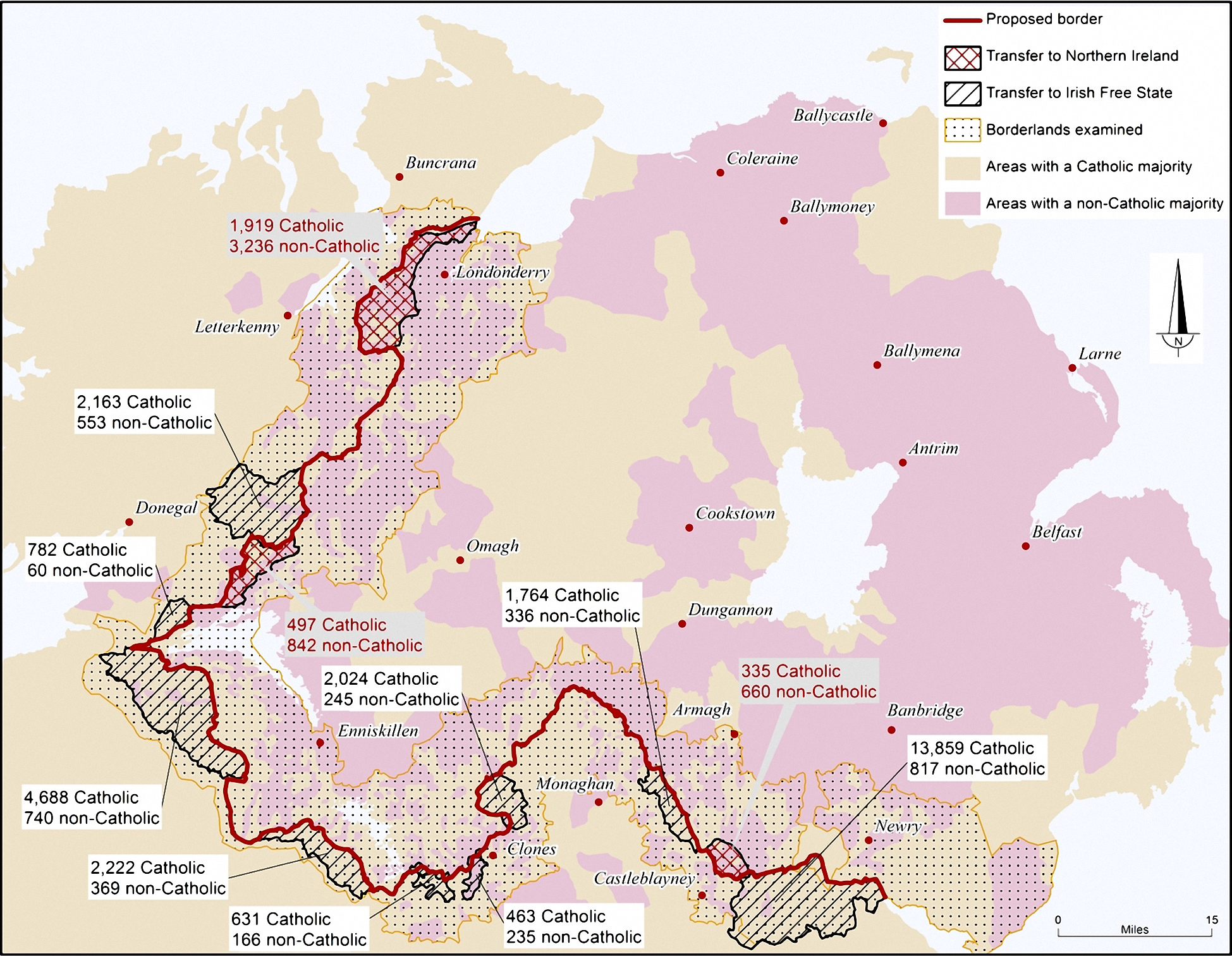

Feetham’s Boundary Commission was to demarcate the actual line of the Irish border, as it was instructed to in Article 12 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921. Feetham was the most important member of that Boundary Commission. In effect, he decided what changes should be made to the Irish border, as he had the casting vote. The Commission refused to consider the 56 boxes of files that constituted the work of the Free State’s North-East Boundary Bureau in 1923 and 1924, as these were not considered by Feetham to be the ‘wishes of the inhabitants’ as expressly defined in Article 12. The Commission also decided not to have cross-examination of submissions; not to employ legal counsel; to make no representations to the press; and for the Commissioners themselves to question witnesses and for such representations to be made available to opposing sides.

NO PLEBISCITE

The Commission’s preliminary tour commenced on 28 November 1924 in Armagh and spent three nights at each of four centres—Armagh, Enniskillen, Newtownstewart and Derry. The Commission met members of Armagh, Monaghan, Fermanagh, Tyrone and Londonderry County Councils, and the Town Councils of Armagh, Monaghan, Newry, Enniskillen, Omagh, Strabane and Derry. At a meeting with Derry nationalists on 21 December 1924 Feetham announced that the Commission did not have the power to establish a plebiscite but would instead rely on 1911 census statistics and election results.

Even before the Commissioners had travelled to Ireland it was becoming apparent that opinions were changing about the Boundary Commission. The Free State had begun to realise, as a result of its early skirmishes with Feetham, that the faith that Collins and Griffith had placed in the Boundary Commission and which led them to sign the Treaty was perhaps misplaced. It was originally expected (or hoped) that the mechanism of the Boundary Commission would, at the very least, result in large tracts of Northern Ireland being transferred to the Free State, perhaps to the extent of making the whole political edifice implode. Northern nationalists were also becoming disillusioned about the likely outcome of the Commission’s findings, and all this was before the Commission had arrived in Ireland to take evidence.

INDIFFERENCE

Nationalists living outside the immediate border areas now knew that, no matter what the final decision of the Commission might be, they were definitely not becoming citizens of the Free State and so they became indifferent to the Commission. That indifference also extended to many in the rural areas well away from Belfast, where it became difficult in many cases to persuade nationalists to act as witnesses. Conversely, opposition to the Commission in unionist areas ameliorated as it became apparent that the Boundary Commission was now hardly likely to become the Trojan Horse for Irish reunification. The three commissioners were met by this indifference when they arrived in Armagh in December. Despite Craig’s fulminating about the Commission visiting Northern Ireland and uttering dire warnings about threats to the commissioners’ well-being, its members toured border areas without security and were reassured by the willingness of unionist politicians to at least meet them. This growing confidence on the part of Northern Ireland unionists was bolstered in the October 1924 general election by the return to government in London of their friends in the Conservative Party.

By the time the Commission held its first sittings to hear evidence in Northern Ireland in March 1925 it had received 130 separate representations, of which 23 were submitted by local authorities, thirteen by other public bodies, 44 from political parties and 50 by private individuals and businesses. Sittings of the Commission were arranged for Armagh on 3–24 March to hear representations from the highly contentious Newry, South and East Down and South Armagh areas. The choice of areas to be reviewed at these sittings indicates, in retrospect, that the Commission always intended to examine local boundary adjustments only rather than wholesale review at county level or above.

Sittings of the Boundary Commission resumed after the Northern Ireland general election on 22 April in Enniskillen and continued until 6 May. They reconvened in Derry, where the Commission had established its Northern Ireland headquarters at the Irish Society in St Columb’s Court, from 14 May until 5 June, and finally in Omagh from 6 June to 2 July. The Enniskillen and Omagh sittings were concerned with representations from Fermanagh and Tyrone respectively, where the nationalist and unionist populations were evenly balanced, but the Derry hearings had more in common with the situation in Newry, where ‘the wishes of the inhabitants’, in both cases overwhelmingly nationalist, had to be balanced ‘with economic and geographic conditions’, as demanded by Article 12 of the Treaty.

CONCERNS ON EITHER SIDE

A total of 575 witnesses representing 58 groups and public bodies and ten individuals were heard. The Commission also received further representations from the Free State on 2 July and 25 August 1925. Throughout the presentations—which were largely co-ordinated through the Unionist Party and the Orange Order on the Protestant side and by the Catholic hierarchy and clergy organising after-Mass meetings to mandate their representatives—there was a consistent thread of similar themes that appear regularly in submissions. On the Catholic/nationalist side these were the assumption that the Anglo-Irish Treaty agreement applied to the whole of Ireland and that unionists were attempting to secede from the independent Irish state; resentment at unionist attempts to disrupt and prevent legitimate nationalist political activity through the abolition of proportional representation in local government, the gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, the demand for an oath of allegiance to the northern state by public bodies and public servants, and the restriction of the electoral franchise; fear of the Special Constabulary (particularly the B Specials) and sectarian attacks; and resentment that the 1923 Free State Land Act was far more generous to ‘unbought tenants’, i.e. remaining tenants who had yet to buy their land from their landlord, than the 1925 Northern Ireland Land Act. Protestant/unionist concerns were a residual fear of the repeat of the assault on the northern Protestant population by the IRA between 1920 and 1922; the belief that the Protestant population had more of an economic stake in the country through being the main ratepayers and that large numbers of Catholics/nationalists were itinerant labourers whose political views were not as important; resentment amongst Protestant communities in Cavan, Monaghan and East Donegal that the Irish language was now a compulsory part of the Free State education curriculum; and the belief that many Catholics were being intimidated into supporting transfer to the Irish Free State.

In many respects both the unionist and the nationalist witnesses at the Commission hearings were similar. They were exclusively male, late middle-aged or elderly, active in or retired from local politics, and members of organisations such as the Orange Order or the Ancient Order of Hibernians. The nationalist case was co-ordinated by the Free State’s North-Eastern Boundary Bureau. It is assumed that unionists were similarly organised by the Unionist Party and the Orange Order, although there is scant documentary evidence of this. There were few contributors from a working-class, labour and trade union background, particularly in Newry and Derry, where the labour movement was beginning to organise—especially in Derry, which in the previous year had experienced extensive labour agitation and strike action.

The subsequent report produced by the Commission was such that both the British and Irish governments agreed that its publication would be detrimental to both countries, and therefore the original county boundaries, in spite of all the submissions considered, remained the international boundary between Ireland and the UK.

Ivan Gibbons is a former Director of Irish Studies at St Mary’s University, Twickenham.

Further reading

I. Gibbons, Partition—how and why Ireland was divided (London, 2020).

I. Gibbons, The Irish Boundary Commission 1925: re-drawing the border (London, 2025).

R. Lynch, The partition of Ireland 1918–1925 (Cambridge, 2019).

K. Matthews, Fatal influence: the impact of Ireland on British politics 1920–1925 (Dublin, 2004).