‘Never reformed because never deformed’

By Yvonne McDermott

During the medieval period Ireland played host to many religious orders, following a range of monastic rules and forms of life, with a common aim of devoting themselves to God. Among the more obscure of these are the Carthusians, whose solitary lives, brief stay in Ireland and foundation of a single house here all served to minimise the attention they have received.

Ireland’s only house of the Carthusian Order, at Kinalehin or Abbey in east County Galway, was in the parish of Duniry, in the diocese of Clonfert. The remains of a late medieval Franciscan friary (with some early modern additions) now stand on this site; the few archaeological traces of the Carthusian house that remain would easily escape notice.

The Carthusians: alone together

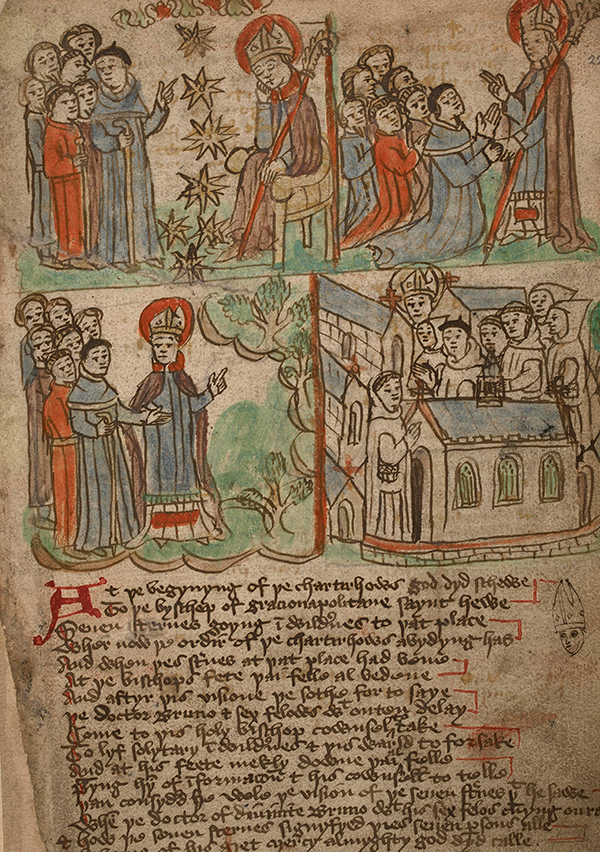

Carthusian monasteries are also referred to as ‘charterhouses’, a corruption of Chartreuse, the place in Savoy where St Bruno founded the original Carthusian community with six followers. Although St Bruno has been widely credited with founding the order, monastic historian C.H. Lawrence has argued that Bruno was its patriarch and Guigo de Pin its principal architect. The monks devoted themselves to poverty, austerity and solitude. They consumed a meat-free diet, taking only bread and water on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. It was their interpretation of the last of the three tenets, namely solitude, that particularly defines this order. The Carthusians were essentially hermits, spending the majority of their day alone, in silence, in their individual cells, which were arranged around a central courtyard. They met as a community in their church twice a day for Matins and Vespers. Hugh of Lincoln accurately summed up their life as a community of hermits: ‘They lived alone lest any should find his fellows an obstacle to him; they lived as a community so that none should be deprived of brotherly help’. In his writings St Bruno discussed the value of solitude, noting that ‘they can dwell apart and attend without interruption to the cultivation of the seeds of virtue and happily eat of the fruit of Paradise’.

The Carthusian statutes identify appropriate uses of the monks’ time in their cells, where ‘the monk occupies himself usefully … reading, writing, reciting psalms, praying, meditating, contemplating, working’. Some of their time should also be devoted to ‘a tranquil listening of the heart, that allows God to enter through all its doors and passages’. The monks ate in their cells, with meals and other necessities being passed through a hatch in the cell door, facilitated by conversi or lay brothers who supported the monks. Each monk had his own private walled garden, and, with practical work being encouraged, many monks worked on book production. Copying of manuscripts was an important task and there is evidence that some monks practised bookbinding. Guigo strongly argued for the value of books for the Carthusians: ‘… books are as it were the everlasting food of our souls; we wish them to be most carefully kept and to be zealously made’. New entrants to the order who could not write were taught to do so.

Silence and solitude

Central to the Carthusians’ way of life and linked to their solitude was the observance of silence, by both monks and conversi. The twelfth-century bishop of Chartres, Peter of Celle, noted that ‘mouths they have, and speak not’, a remark not intended negatively, as was the case where these words were cited in the psalms. The Carthusians believed that on the Day of Judgement they would be held responsible for any careless utterances. The statutes of the order indicated that the value of silence became evident through experience: ‘there is gradually born within us of our silence itself, something that draws us on to still greater silence … God has led us into solitude to speak to our heart’.

Many observers, including the popes, admired the Carthusians’ commitment to their founding principles. Nunquam reformata quia nunquam deformata (‘never reformed because never deformed’, or ‘never in need of reform’ in some translations) is a phrase that has been used to describe the order, which did not adopt the Observant reform of the religious orders in the late medieval period as they had not strayed from their founding principles. They did, however, promote the reform in other orders, some of which embraced aspects of the Carthusian life as part of their reform. Thus the Carthusians wrote treatises for reforming houses and visited them to help institute the reform. In addition, some individual Benedictines and Cistercians left their own orders to become Carthusians.

The early church in Ireland had a strong impulse towards the eremitical life, seeking the spiritual desert in places of solitude in Ireland and beyond. The impetus towards the solitude practised by the Carthusians had long existed in the Irish church but the high and late medieval period saw community-based forms of religious life dominate. The Carthusian abbey in Kinalehin represented both the start and the end of their order’s experience in Ireland. This house scarcely lasted long enough to be in need of reform, had indeed such a requirement arisen amongst the Carthusians.

The charterhouse at Kinalehin

Ireland’s only charterhouse was established c. 1252 by John de Cogan, son of Richard and Basilia de Cogan. He has also been credited with founding Claregalway Franciscan friary. England’s first two charterhouses, both of which were in Somerset, were established at Witham (1179–80) and Hinton (1232). Kinalehin was the next house to be established and was likely peopled from one or both of these foundations. It appears to have sustained some damage in 1279 but was rebuilt. Edward I granted letters of protection to the prior, monks and lay brothers of Kinalehin in 1282.

Kinalehin was to be a short-lived establishment. It seems to have lasted for approximately 40 years, with ensuing attempts to wind up the house dragging on subsequently. The priory was officially suppressed at the 1321 Carthusian General Chapter. It was no longer occupied by this time and the English Carthusians decided not to send any more monks there. The diocese took over the site c. 1341.

Various explanations have been offered for Kinalehin’s lack of success. The nature of the monks’ existence meant that they lacked a public presence and awareness of the order may have been limited. The order does not seem to have been successful in attracting Irish members. With so many competing forms of religious life in Ireland at this time, perhaps a solitary life was less appealing. It is worth noting that the order was also slow to grow in England during Kinalehin’s lifespan but it experienced modest growth later on, in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This might be a reflection of increased emphasis on the contemplative life in devotional literature at that time, added to a desire to discover more authentic monastic experiences, as evidenced by the Observant reform in other orders. Interestingly, a single Scottish house of the order was founded at Perth in 1429, while no Carthusian priories were established in Wales. Elsewhere in Europe the order grew slowly (but consistently), with communities tending to remain small in size, typically consisting of twelve to fifteen brothers. Their later expansion saw the order establish new houses in urban areas, in contrast to the rural locations that distinguished early charterhouses, such as Kinalehin.

Witham and Hinton may provide some insights into the layout of Kinalehin priory. Both consisted of a ‘great cloister’ around which the monks’ cells were arranged, forming the upper house. A lower house centred around the ‘little cloister’, consisting of the lay brothers’ quarters and other conventual buildings. The church completed the monastic complex. Excavations at Kinalehin indicated a bipartite arrangement of the buildings at the site. This arrangement was not used in the late English Carthusian houses, where the lay brothers were accommodated in the same enclosure as the ‘fathers’.

The Knights and Franciscans

The association of the Knights Hospitaller with Kinalehin has been the subject of some debate. Investigations have produced no compelling proof of the existence of a priory of the order at Kinalehin, a suggestion that appears to have originated from an error in the writings of seventeenth-century antiquarian Sir James Ware. It appears that the Knights held the rectory and title of the site until the Dissolution of the Monasteries but never established a priory there. This wealthy order also owned other benefices in Connacht. The Franciscans arrived in Kinalehin c. 1371; this was the first new house of the Grey Friars to be established in Ireland since 1325. From this point onwards the profile of the site increased, with the construction of new buildings, evidence of patronage and a community that endured into the seventeenth century—a testament in part to the outward-facing, community-focused work of the Franciscan friars. The Carthusians’ fleeting presence at the site proved as discreet as their lifestyle.

Yvonne McDermott lectures on the History and Geography programme at GMIT Mayo campus.

FURTHER READING

C.H. Lawrence, Medieval monasticism: forms of religious life in Europe in the Middle Ages (London, 2015).

D. MacCulloch, Silence: a Christian history (London, 2013).

Y. McDermott, ‘Kinalehin, Co. Galway: a history of Ireland’s only Carthusian priory and its conversion to a Franciscan friary’, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 142–3 (2012–13), 100–13.