Thomas Bartlett

Irish history without a Catholic question might seem as improbable as Irish history without the potato: all Irish history, at least from 1550 onward, can be regarded as an extended comment on the Catholic question. None the less, to contemporaries, British and Irish, the term the Catholic question had a precise meaning: it signified the issue of the re-admission of Catholics to full civil, religious and political equality in both Britain and Ireland and it denoted the timing – at what point could such concessions with safety be made – it denoted the terms – with what safeguards could such concessions be made – and it denoted the sponsorship – under whose auspices should these concessions be made. But behind the public face of the Catholic question lurked its hidden face – a complex matrix of political calculation, strategic consideration and military necessity: it may be that most interest attaches to precisely these aspects of the Catholic question.

The Protestant ethos of the British State

In the context of British politics, the question of political and religious rights for Catholics could be no ordinary political issue: not only did it raise matters which affected all religious groups – including Jews, Quakers and Presbyterians – who refused to subscribe to the established church and who suffered consequent disadvantage, but in so far as it related explicitly to Catholics it directly challenged the Protestant ethos of the British state. Important as the Catholic question undoubtedly was in British politics, however, it was still possible to view it more or less dispassionately: such detachment was not possible in Ireland and there the question was seen by most Protestants as a matter of life and death.

Like Britain, eighteenth-century Ireland was a Protestant country in which all political power and most social and economic consequence was confined to those who conformed to the established church; but unlike the situation in Britain, Irish Protestants were keenly aware that they constituted a minority of the Irish population; although they might like at times to disguise, ignore or forget this unpalatable fact by claiming to be the ‘Protestant nation’, the ‘whole people of Ireland’, or even the ‘Irish nation’, such claims were more notional than real. Irish Protestants were well aware that the sole basis of their claim to be not just a people but the people of Ireland lay in the destruction of Catholic power, the confiscation of Catholic land and the concurrent denial to Catholics of social and political authority. Hence their anxiety when something called the Catholic question emerged in Ireland in the late 1760s.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE CATHOLIC QUESTION

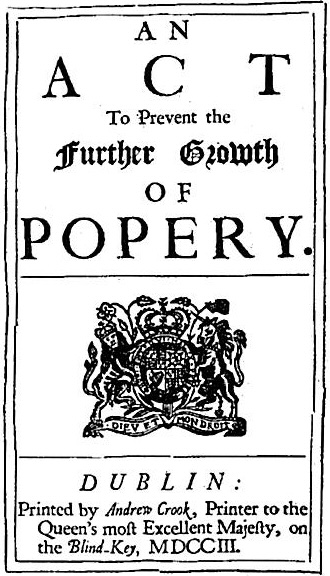

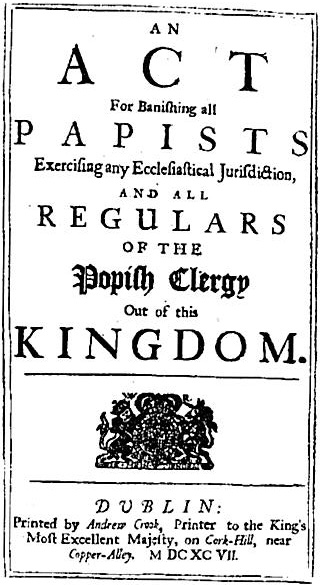

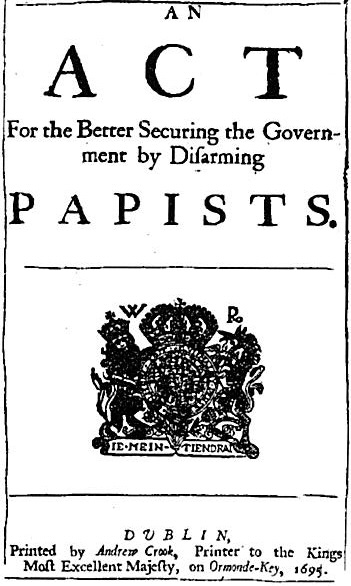

The emergence of the Catholic question and, especially, the speed with which it came to dominate the Anglo-Irish political agenda, cannot but have alarmed Protestant opinion in Ireland. After all, the crushing victories at the Boyne and at Aughrim seemed to have put all hopes of a Catholic resurgence quite out of the question. Moreover, in order to make security doubly secure, a series of piecemeal Penal Laws had been enacted which, cumulatively, seemed to ensure that hopes of a Catholic recovery would be forever forlorn. Again, the steady support of English opinion, which fully shared Irish Protestant apprehensions of the Catholic menace, had also augured well for the future. The presence of an Irish parliament on a regular basis was also reassuring, for Irish Protestants well remembered that the absence of such an institution in the seventeenth century had usually meant danger for them. The departure abroad of the ‘Wild Geese’ further reduced the number of potential leaders and also the amount of combustible material on the island. Given that the Catholic question appeared to have been once and for all resolved by the beginning of the eighteenth century, how then can its re-emergence be explained by the 1760s?

One answer would be that a decent interval had elapsed since the 1690s and that Catholics had shown by their good conduct during the decades since then, especially by their silence during the Jacobite threats in Scotland in 1715 and 1745, that they deserved favour. Certainly, Catholic spokesmen such as Charles O’Conor made much of the good conduct of Catholics during the early eighteenth century and it is possible that his words had some effect.

THE ENLIGHTENMENT

Again, it could be argued that the ideas of Enlightenment were having an influence on Ireland by mid-century for, by this time, notions of persecution for religious belief were generally reprobated throughout Europe: the embarrassment which the nineteenth century historian James Anthony Froude claimed to have been the prime Protestant reaction to the Penal Laws may have become even more acute in the glare of Enlightenment.

One needs to be careful here, however, for central to the Enlightenment was a virulent anti-Catholicism and this is evident in the works of Voltaire, Montesquieu, Diderot and D’Alembert. In their writings, the teachings, organisation and claims of the Catholic church were mercilessly parodied and pilloried and the church itself was cast as the biggest single obstacle to the spread of enlightened ideas. When Daniel O’Conor, Charles’s brother, complained to the famous French philosopher, Claude Helvétius, he was brusquely advised to become a Protestant. When O’Conor said that he could not give up the most essential articles of his faith, Helvetius had merely replied ‘and where the devil would be the great harm in that, surely you are not so idle as to have any regard to these fooleries?’ In short, Irish Protestants could legitimately comfort themselves that the Penal Laws, by putting a penalty on adherence to superstition and general ignorance, were actually forwarding the work of the enlightenment. That said, the Penal Laws were increasingly difficult to justify as the decades wore on.

and John Hayter(Ulster Museum)

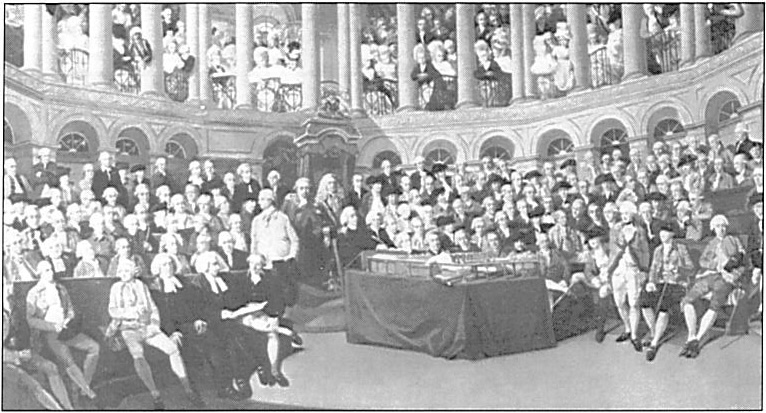

The presence of Irish parliament on a regular basis was also reassuring for Irish Protestants well remembered that the absence of such institution in the seventeenth century had usually meant danger for them.

CATHOLIC MERCHANT CLASS Another reason frequently advanced for the emergence of the Catholic question around mid-century was the perception that a wealthy Catholic merchant class had grown up and that Catholic money, because of the Penal Laws, was shut out of the Irish economy, the land market in particular. Catholic spokesmen and Protestant sympathisers made much of this point and it may have had some effect. Once again, however, one needs to be careful before one accepts this argument at face value. A Catholic merchant class had undoubtedly grown up under cover of the Penal laws, but it was debatable whether Catholic money was in fact locked out of the land market, for lease speculation was available to those who wished to invest in land.

PROTESTANT DIVISION

It may be that the chief reasons for the emergence of the Catholic question by 1760 lie in changes within the political world of Protestant Ireland and also in developments within the Anglo-Irish relationship itself.

By the mid-1750s, Protestant union had been replaced in Ireland by Protestant division, for the Lucas affair of the late 1740s, and especially the Money Bill dispute of the 1750s, showed new divisions within the Protestant political world. During this latter conflict, the Speaker of the Irish Parliament, Henry Boyle and his connection, had done battle with the followers of John Ponsonby and with those politicians who generally adhered to the Castle’s viewpoint. Boyle and his confederates had represented the struggle as an epic one for Ireland’s liberties: one participant noted that the cry through the country was ‘Ireland for ever’ and sometimes with the addition of ‘Down with the English’: and the outcome was generally regarded as a victory for the Boyle squadron. But by introducing the Protestants of Ireland to the delights of politics, by extending the political constituency far beyond the parliament at College Green, Boyle had embarked on a highly dangerous game. It was not just that division among Irish Protestants had always been taken advantage of by Irish Catholics: more than this, if Boyle could appeal to the Protestants beyond the walls of parliament in opposition to the wishes of the British government and its agents in Dublin Castle, then so too could the British government appeal to another group or groups hitherto excluded from the political world – perhaps the Presbyterians or the Catholics or both. In the history of the rise of the Catholic question, the Money Bill dispute of the 1750s marked a watershed for it sowed divisions among Irish Protestants and aroused suspicions in the minds of British ministers about the reliability of Irish Protestants. In creating these tensions among – and between – the governing elites of Ireland and England, the Money Bill dispute gave Irish Catholics their chance to stand forward. It comes as no surprise to learn that it was at the time of the Money Bill dispute that a Catholic committee of sorts was convened to consider Catholic grievances and to seek redress.

ANGLO-IRISH RELATIONS

It was in the 1750s that the chemistry of the Anglo-Irish relationship began to change decisively. The growth of a Protestant nationalism in earlier decades and its manifestations in the 1750s and 1760s alarmed English politicians and led them to contemplate new alliances in Ireland in order to restrain the exuberance of Irish Protestant self-assertion. It is important not to exaggerate here; there was never any question of replacing the Protestant interest with the Catholic one. None the less there is evidence that from the 1760s on British ministers saw it as common sense to keep on good terms with Irish Catholics, if only to remind Irish Protestants that, though they might call themselves the people of Ireland, there was another people on the island who could equally lay claim to that title. A further boost to this more flexible attitude was given by the perceived international weakness of the papacy, the consequent disappearance of the Catholic threat and the final collapse of the Stuart cause. A shared anti-Catholicism had been an important bond between English and Irish Protestants. With the decline of hostility to Catholics in England, at least at élite level – a decline consequent on a perception of the Papacy’s weakness and the Stuart collapse – Irish Protestants would increasingly have to explain their fears and justify their exclusionist Penal Laws in terms that English ministers might no longer find readily intelligible.

THE EXPANSION OF EMPIRE AND THE SINEWS OF WAR

Furthermore, from the 1760s on, the concerns, anxieties and fears of Irish Protestants would have to take second place to the very real needs of the empire and also to the requirements of the armed forces of the crown. If a single overarching explanation for the emergence of the Catholic question and the timing of the repeal of the Penal Laws in the late eighteenth century is sought, then that explanation is to be found in the expansion of empire and especially in the scale and extent of warfare from the 1760s on. There is a certain irony in this; the Catholic question in the early eighteenth century had also been linked to the threat of war. Irish Catholics had been seen as Jacobite in sympathy and thus inherently disloyal; they maintained what amounted to a standing army abroad – the so-called Irish Brigade in the service of France – which recruited clandestinely among Irish Catholics; and when wars did break out – as for example in 1743 at the start of the War of the Austrian Succession – it was usual for extra security precautions to be taken against them. But from mid-century on, all this changed: war would henceforth mean opportunity rather than danger for Irish Catholics. It would provide an opportunity to parade their loyalty, an opportunity to draw up addresses of support and especially the possibility of bartering recruits for concessions. Military necessity, essentially the manpower requirements of the British army, provides the context for the emergence of the Catholic question in the 1760s and its persistence thereafter.

CATHOLIC RELIEF FOR CATHOLIC RECRUITS

Throughout the 1770s, as relations between Britain and her colonies in North America deteriorated, Catholic recruits were taken into the armed forces in increasing numbers. Not surprisingly, Irish Protestants grew restive at this development: there were protests at the open recruitment of Irish Catholics into the East India Company army, and alarm was expressed at reports that 10,000 Catholics were to be enlisted for the defence of Ireland. Protestants began to suspect that the British government in its eternal quest for troops was not above offering Catholic relief in return for Catholic recruits. Nor were their suspicions groundless, for there was in fact a plan to offer concessions to the Catholics of England, Scotland and Ireland, and this scheme formed the background to the Catholic Relief Act of 1778, the first major breach in the Penal code.

This act repealed some of the Penal Laws concerning ownership of land by Catholics but its main aim was to encourage the Catholic gentry to beat the recruiting drum and enlist their co-religionists into the British army. It was Luke Gardiner, long on record as a supporter of Catholic recruitment into the army, who introduced the Relief Bill and it was put through the Irish parliament in June 1778. This Act set the seal on Irish Catholic support for the war against what the Catholic bishop of Dublin, John Thomas Troy, dubbed ‘the Puritan party, calvinistical and republican’ in the American colonies. It firmly established the principle of Catholic relief as a key element of war-time strategy.

THE VOLUNTEERS

Towards the end of the American war, another major Catholic Relief Act was passed and this 1782 Act effectively repealed those Penal Laws directed specifically at the practice of the Catholic religion. This time, however, the concession was not granted with an eye to recruits but with an intention of keeping Irish Catholics detached from the Volunteers. This military force, set up independently of Dublin Castle during the emergency of the American War to defend Ireland from coastal attacks or even from invasion, had – to the alarm of Dublin Castle – quickly turned its attention to political and constitutional matters and had demanded redress of grievances. The offer of concessions to Irish Catholics in 1782 was designed to isolate the Volunteers and their supporters and thus render their demands for constitutional reform both partial and partisan and thus vulnerable. If this was the plan, then it totally failed for the Volunteers at their Convention in Dungannon took up the Catholic cause and declared their delight at the removal of restrictions on their fellow-subjects. Deprived of its Catholic card – for the Volunteers’ declaration at Dungannon had trumped it – the British government could not resist the constitutional demands being made in Ireland and were forced to concede ‘the constitution of 1782’. It was no coincidence that the Constitution of 1782 and the Catholic Relief Act of 1782 went through at about the same time for the two were intimately linked. Indeed, from the vantage point of hindsight, it may be said that the two Catholic Relief Acts of 1778 and 1782 illustrate perfectly the element of political calculation, the measure of threat and indeed the sheer politics of the Catholic question in Ireland at this time.

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

These aspects of the Catholic question were much in evidence in the early 1790s. In the highly charged atmosphere produced by the French Revolution, the matter of relief for Catholics was once again actively canvassed. During the 1780s, the Catholic question had remained in abeyance, for the British government had not forgiven the Catholic body for siding with the Volunteers in 1782 and had more or less turned its back on them. The Catholics, having been courted by the Volunteers, had soon been abandoned by them: the Volunteer plan for parliamentary reform made no attempt to include Catholic franchise or representation. This parliamentary reform campaign which the Volunteers embarked on in the early 1780s quickly ran out of steam: but from the failure of that campaign, certain lessons were learnt by the more committed reformers. The chief of these was that any future reform movement had to enlist the support of the Catholics if it was to make any headway: by ignoring the Catholics when the reform proposals were drawn up, the reformers were convinced that they had encompassed their own downfall. They resolved not to make the same mistake again. In this resolution lay the seeds of the future Society of United Irishmen.

THE UNITED IRISHMEN

This society was set up in Belfast in October 1791 and aimed to curb the influence of England in the government of Ireland through a thoroughgoing parliamentary reform. Central to that endeavour was the conviction that, as Theobald Wolfe Tone put it, ‘no reform is practicable that does not include the Catholics’. The British government was sufficiently alarmed at the possibility of an alliance between the Northern Dissenters, Irish Catholics and Dublin radicals that it urged that major concessions be made to the Catholics in order to head off this development. Dublin Castle resisted this argument and the concessions offered in 1792 fell far short of those which the Catholic Committee – now much more assertive than hitherto – demanded; and indeed were much less than the British government felt necessary. Further sweeping concessions were required and in 1793 most of the remaining penal laws were repealed. In a startling innovation, the parliamentary franchise was extended to Irish Catholics on the same terms as Irish Protestants: it seemed to be only a matter of time before Catholics were restored to full political equality in Ireland.

THE CATHOLIC RELIEF ACTS of 1792-3

The scale of the concessions of 1792-3, so far-reaching as to merit the term revolution, requires explanation: the discrepancy between that which was on offer to the Catholics in 1792 and that which they finally received in 1793 also needs examination. Once again, the explanation can be located in that area where political considerations and military requirements intersected. The reconfiguration of Irish politics threatened by the United Irishmen was viewed with the gravest alarm by the British government and hence no steps were spared to prevent it. The United Irishmen were harassed, the Volunteers were suppressed, a ban was placed on Conventions like that of 1782 and the Catholics were bought off. But the urgency with which the issue was treated, and the sharp rise in the concessions on offer, can only be fully understood by reference to the threat of war and the needs of Irish defence. If the American war had seen the recruitment of Catholics for service overseas, then the war with France would see them enlisted not alone for service abroad but also for home defence: this constituted a major departure in military strategy. At the same time that the vital Catholic Relief Bill of 1793 was going through the Irish parliament, a Militia Bill authorising the embodiment of some 20,000 militiamen – the vast majority of them necessarily Catholic – for the defence of Ireland was also proceeding through the legislature. It was no coincidence that the two bills reached the statute books together. Nor was it a coincidence that war broke out with France as these two Bills gained the royal assent. A year earlier, Dublin Castle had succeeded in whittling down the very modest concessions then offered to the Irish Catholics but in the winter of 1792-3 the situation on the continent had deteriorated appreciably and war loomed. Time and time again the Prime Minister William Pitt made the point that ‘the present state of the world’ made it vital to adopt such measures as would ‘conciliate the Catholics as much as possible and … make them an effectual body of support’. There could be ‘no reason why in respect of arms they [Irish Catholics] are to be distinguished from the rest of his majesty’s subjects’. Therefore not only were Irish Catholics to be permitted, even coerced, into forming a defence force for their country but also in an equally radical departure from previous practice they were to be given commissions in the British army, if appropriately qualified. Within a generation, the British state had gone from a policy of firm exclusion of Catholic soldiers to one of forced inclusion; from fear of Catholic numbers to reliance on them to meet the needs of war.

CLOSING THE CONCESSION ACCOUNT

In 1793, with Irish Catholics having the vote on the same terms as Irish Protestants, and with their playing a front-line role in the defence of Ireland in the event of a French invasion, it might have been assumed that the Catholic question was now over. But this was not to be the case. The final citadel of Protestant government – the right of Catholics, if elected to take their seat in parliament – proved elusive. Mounting violence in Ireland, widespread evidence of a well-organised conspiracy to subvert the government, and the prospect of a long war against France combined to make British ministers close the concession account where Irish Catholics were concerned. At one time, during the viceroyalty of Fitzwilliam in early 1795, it appeared certain that Catholic emancipation, as it was now called, would be conceded but Fitzwilliam was recalled and the moment passed. Again at the time of the Union, Catholics were certainly encouraged to expect concession from that ‘impartial legislature’ which the union of the two parliaments would bring about. But once again, the Catholics were to be disappointed: to them, the Act of Union would appear little more than a new penal law, and their disappointment over emancipation continued until nearly thirty years into the nineteenth century. Long before then however it was clear that Catholic emancipation would never be given; it could only be taken. And this could only be achieved when the Catholic question was divorced from party politics and from questions of defence and military strategy. The Catholic question could only be addressed properly when it was finally recognised for what it now was – or in fact may have been all along – the Irish question.

Thomas Bartlett lectures in modern history in University College, Galway.

Further reading:

Thomas Bartlett, The Fall and Rise of the Irish Nation: the Catholic Question 1690-1830 (Dublin 1992).

Kevin Whelan and Tom Power (eds.), Indurance and Emergence: Catholics in Ireland in the Eighteenth Century (Dublin 1990).

Gerard O’Brien (ed.), Catholic Ireland in the Eighteenth Century: the essays of Maureen Wall (Dublin 1989).