On 22 October 1641 the native Irish of Ulster, led by Sir Phelim O’Neill, captured a number of key towns and fortifications in the province. An alliance was soon forged with the old English Catholics of the Pale and by the end of the year the revolt had spread throughout the country. After an initial period of chaos and confusion, the rebels began to organise themselves, united by their adherence to an oath of confederacy. By this oath the confederate Catholics, as they came to be called, swore to defend the king’s prerogatives and their own lives and liberties against a corrupt administration in Dublin and an increasingly aggressive Puritan parliament at Westminster. Irish Catholics’ strong sense of national identity was perfectly compatible with personal loyalty to the crown. Charles I was king of Ireland by virtue of an act of the Irish parliament and his authority there functioned independently of his authority in England. The confederate stance was neatly articulated in the motto ‘pro Deo, pro rege, pro patria Hibernia unanimis’.

Reluctant rebels

With the outbreak of civil war in England during the summer of 1642, government forces in Ireland split into royalist and parliamentarian factions, while the Scots covenanters, allies of the English parliament, sent a large army to Ulster to protect their own settler interest. For the next three years, despite the large number of troops in the country, the fighting was confined to minor skirmishes, sieges and supply raids, with no one side gaining a decisive advantage. This sporadic warfare was accompanied by almost continuous negotiations between the confederates and the royalists, led by the protestant lord lieutenant, James Butler, Earl of Ormond. The confederates, uncomfortable in the role of rebels, were anxious for a reconciliation with the crown and eager to join forces against the king’s ‘real’ enemies, the parliamentarians and the Scots. The contentious issue of religious concessions for Catholics, however, prevented the conclusion of any agreement.

Alienated from the crown and anxious to provide some semblance of law and order, the confederates began to construct alternative power structures, centred in the city of Kilkenny (hence the popular title, ‘confederation of Kilkenny’). As a result of these efforts, there emerged a far more sophisticated, dynamic and in many ways progressive political system than has hitherto been recognised. This is particularly true of the General Assembly, which after 1645 developed into a powerful national institution, dominant in confederate affairs. The interplay of forces within that assembly and its relationship with the executive Supreme Council played a decisive role in determining the course of events during this crucial decade in Irish history.

The General Assembly

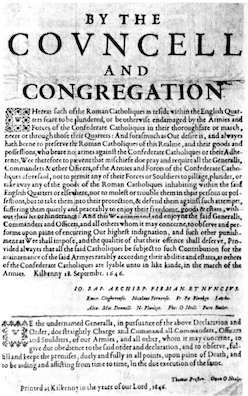

The General Assembly of the Confederate Catholics of Ireland met nine times between October 1642 and January 1649. A unicameral assembly where lords, clergy and commoners all sat together, it functioned as a central forum where issues of national importance could be discussed. The assembly enjoyed a wide geographical representation, covering all four provinces, but the franchise was restricted to male freeholders of forty shillings a year upwards. According to the confederate ‘model of government’ developed during 1642, supreme authority resided in the assembly, and its consent was necessary in resolving the major questions of peace and war.

This arrangement was always seen by the confederates as a temporary expedient until they were able to reach an accommodation with the Stuart monarchy and for this reason the assembly deliberately avoided the title ‘parliament’. Nonetheless, in the words of a leading confederate, every effort was made ‘to keep us as near to the old government as we might be’ and to facilitate the exploitation of existing structures. Writs were issued for elections to the assembly based largely on old constituency boundaries. Royal taxes were diverted to finance confederate troops and administrators, while the judicial system continued to function with minimal changes.

The Supreme Council

Before dispersing, each General Assembly elected an executive body of twenty four members, called the Supreme Council, which was responsible for the day-to-day administration of confederate-controlled areas. This council sat continuously, though in theory it surrendered authority whenever an assembly was in session. In practice, however, the Supreme Council, dominated by a small powerful clique of landowners and lawyers, gradually assumed a dominant political role, particularly regarding the crucial negotiations with the royalists. By 1644 the assembly, effectively stripped of power and lacking any clear sense of purpose or identity, became nothing more than a rubber stamp for the council’s decisions. Poor attendances and insipid debates were further indications of its diminished role.

Glamorgan’s secret commission

All this began to change from the summer of 1645 onwards. In June of that year the royalist forces in England were crushed at Naseby, a defeat which left Charles I without a standing army. In the desperate search for troops which ensued, accommodation with the confederates now became an urgent necessity. That same month, Edward Somerset, the Earl of Glamorgan, arrived in Ireland with a secret commission from the king giving him wide and undefined powers to negotiate a settlement. The authenticity of this commission was, and continues to be, the subject of controversy, though crucially it was accepted as legitimate by the confederates. The earl’s willingness to offer major religious concessions to the Catholics proved decisive in breaking the deadlock in the peace talks.

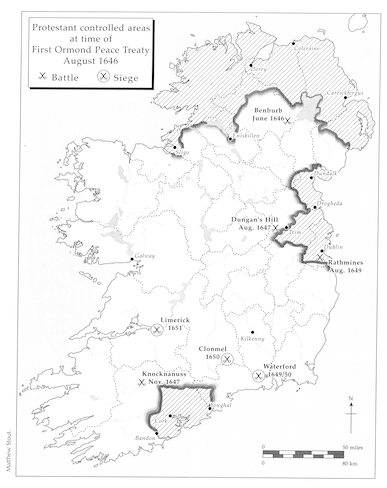

A compromise was agreed by which the final settlement was divided into two components — a secret agreement with Glamorgan on religious matters and Ormond’s public treaty dealing with political and military affairs. This arrangement was fatally compromised when the English parliament obtained, and published, a copy of the secret treaty. Worried about the political repercussions in England of this disclosure, Charles I quickly repudiated Glamorgan. As a result, serious divisions began to emerge in confederate ranks. One group favoured pushing ahead with Ormond’s treaty alone, while another, encouraged by Eoghan Ruadh O’Neill’s crushing victory over the Scots at Benburb, argued that without religious concessions, no settlement was acceptable. In August 1646, despite significant opposition, the Supreme Council published the Ormond Peace treaty, precipitating an open breach between the hostile factions.

Factional conflict

A party or faction in the seventeenth century was not a clearly defined entity with the strict internal discipline we associate with such groups today but a loose coalition of men shading off to the mass of the uncommitted. The destruction of assembly records in 1711 makes individual political allegiance difficult, but not impossible, to ascertain. It appears that the majority of assembly members were not associated with any particular grouping. Few had any political experience at national level. They were spokesmen for their own communities who voted according to personal or local interests. After 1645, however, with the development of factional conflict, it became increasingly difficult to maintain a neutral position.

The Ormondist (peace) party

This struggle between the Ormondist and clerical factions is the dominant theme of studies on the period. The Ormondists or peace party are a clearly identifiable group of the lord lieutenant’s Catholic relations, retainers, tenants and friends, whose remarkable cohesion throughout the turbulent decade gave them a disproportionate influence on confederate affairs. The leading figures in this faction (Viscount Muskerry, Richard Bellings and Doctor Gerald Fennell) are well known and played a major role in the political, military and diplomatic spheres. Not surprisingly, accommodation with Ormond and the royalists was their primary aim and they favoured using ‘safe’ aristocratic generals, like Viscount Taaffe and the Earl of Castlehaven, who could be guaranteed not to campaign too vigorously. Crucially, the Ormondists were prepared to postpone the question of religious concessions until the king had won the civil war in England.

The clerical (war) party

The clerical or war party on the other hand was a less coherent body. At its core were the bishops and clergy who, when they spoke with one voice, presented a formidable front. Allied with them at various times, but for different reasons, were counter-reformation Catholics, those dispossessed by the plantations, and a general anti-Butler interest. Edmond Dempsey, bishop of Leighlin and Geoffrey Barron were leading figures in this faction, but unquestionably the dominant personality was the papal nuncio, Rinuccini, who reached Ireland from Rome in November 1645. The war party also favoured an agreement with the royalists, but at a higher price—state recognition for the Catholic church in Ireland and a reversal of the plantation policy, particularly in Ulster. They sought to dictate peace terms following a decisive military victory and their favourite, though by no means always compliant, general was Eoghan Ruadh O’Neill.

This straightforward division of confederates into peace and war factions is unsatisfactory, however, in explaining developments at this time, particularly the crucial events of August 1646. In that month, having published the Ormond treaty, the Supreme Council sent two of its members, Nicholas Plunkett and Patrick Darcy to the ecclesiastical congregation meeting in Waterford. Plunkett, chairman of the General Assembly, and Darcy, confederate ‘chancellor’, were two of the most respected lawyers in Ireland, well versed in the art of persuasion. They were leading proponents of peace and had been intricately involved in drawing up the treaty with Ormond. Their task was to convince Rinuccini and his allies to accept the limited terms on offer from the royalists. Shortly after arriving in Waterford, however, both men suddenly switched sides and denounced the treaty.

A centrist party?

The conventional explanation for this abrupt turn around has been that Plunkett and Darcy, as devout Catholics, were beguiled by the papal nuncio. A more plausible scenario is that this switch in allegiance was a deliberate move, which signalled the emergence of a centrist position in confederate politics, a middle group. For the next two years the political scene in Kilkenny was divided not into two, but rather three strands, which corresponded very closely to the peace, war and middle groups in the long parliament at Westminster. This middle group was a joining together of moderate men for specific though limited ends. Their main aim was to preserve confederate unity by encouraging consensus and co-operation. They were anxious for peace, but not an abject one, and for a time their policies prevailed as the most workable compromise between the irreconcilable extremes of peace and war.

It is difficult to pinpoint who belonged to this middle party as they exercised their influence by supporting one of the other two factions, and tended therefore to get lumped in with them. The leaders, however, are clearly identifiable. Apart from Plunkett and Darcy there was Nicholas French, Hugh Rochfort and for a time Randal MacDonnell, Marquis of Antrim. French, the bishop of Ferns played a vital role as ecclesiastical counterbalance to the more extreme papal nuncio. Rochfort’s extensive connections throughout the south east provided a link with the urban/merchant élite, while the enigmatic Antrim had considerable military and financial resources available to him. Between them these men controlled confederate politics until early 1648.

By abruptly ‘changing sides’ in August 1646, Plunkett, Darcy and their allies helped overthrow the first Ormond treaty, enabling the war party to gain a temporary ascendancy. Supporters of the treaty were imprisoned and a major attack launched on the royalist stronghold of Dublin. This offensive was a miserable failure and in the chaos and confusion which ensued, Plunkett and French forced two crucial decisions through the new Supreme Council. In order to facilitate a reconciliation, all political prisoners were released and a General Assembly called to adjudicate in the dispute over the Ormond Peace. This latter tactic helped propel the assembly to the forefront of confederate politics, a position it never subsequently relinquished.

The emergence of the General Assembly as a more active component in political affairs had already begun the previous summer, 1645. After his arrival in Ireland, the Earl of Glamorgan, despite a direct request, had refused to negotiate with the General Assembly and insisted instead on dealing with the Supreme Council. Already resentful of the council’s usurpation of power, the assembly members decided not to allow this public humiliation to go unchallenged. They issued a statement that the confederate union was to stay in place until peace terms had been ratified in a full parliament, not withstanding any declaration to the contrary. This was an unambiguous warning to the council not to conclude any treaty without consultation and is the first indication of the assembly’s willingness to adopt the central role outlined for it in the confederate ‘model of government’.

New sense of corporate identity

The development of a new sense of corporate identity within assembly ranks was confirmed during the next session in January 1646. Anxious to conclude the treaty with Ormond, the Supreme Council refused to yield up power to the assembly. A major crisis was averted only by an unlikely alliance between the peace and war factions. In return for a number of concessions, Rinuccini and his allies agreed to help quell discontent among assembly members. This was done with vague promises of future consultations. With the outbreak of factional conflict, however, the middle group used its balance of power in the assembly not only to consolidate its own position, but also to give voice to the assembly’s growing independence.

‘Much acrimony in public’

Deciding the fate of the Ormond treaty was the primary business of the seventh General Assembly which met in January 1647. According to one contemporary report there was ‘much acrimony in public’. Eventually, after three weeks of heated debate, a compromise formula, sponsored by Plunkett, was adopted, by which the treaty was declared invalid, but its authors, including most of the middle group leaders, were exonerated from any blame. Rinuccini, although unhappy at this verdict, grudgingly acknowledged that it commanded the support of the vast majority of assembly members. A leading proponent of peace, Robert Talbot reluctantly accepted the compromise, but commented acidly that the treaty was ‘overborne with vote, not weight or strength of reason’. For the moment, unity, however fragile, had been preserved.

The next crisis facing this assembly concerned the vital oath of association taken by all confederates. The war party sought crucial amendments of its religious articles to ensure the changes would be included in any future treaty. These amendments were denounced by their opponents as ‘impossible undertakings’ and with dissensions raging more bitterly than ever, it took a compromise once again to prevent the outbreak of factional conflict. The assembly agreed to the changes to the oath, but it was to have the final say on any peace terms.

The final act of the assembly was to elect a new Supreme Council. Although described as the ‘council of the clergy’ in some contemporary accounts, this council was not in fact controlled by the war party. At least four members belonged to the peace party including, at Plunkett’s insistence, its leader Viscount Muskerry, while the middle group was well represented by Plunkett himself, along with Darcy, French and Rochfort. The Marquis of Antrim was elected president. He was the perfect compromise candidate with his strong royalist record, extensive family connections across the political divide and good personal relations with the papal nuncio.

The seventh General Assembly represented a major victory for both the middle group and the assembly itself. The unacceptable treaty with the royalists was rejected but not at the cost of confederate unity. The new Supreme Council was neatly balanced but most importantly, the assembly, through the revised oath of association gained total control of the peace process. Its power, and therefore that of the middle group, was, according to Richard Bellings, ‘unlimited’.

Disastrous defeats

In the months that followed, the middle group argued for a vigorous military campaign against the Scots and parliamentarians while still hoping to reach accommodation with the royalists. Ormond’s flight to England leaving Dublin in parliamentarian hands and the subsequent disastrous defeats of confederate forces at Dungan’s Hill and Knockanuss seriously undermined the credibility of this policy. The next General Assembly in November 1647 met in an atmosphere of increasing frustration which benefited the extremists in both the peace and war factions. To avoid a split, the whole question of a peace settlement was postponed and delegates sent abroad to seek urgent financial and military aid. Plunkett and French were to lead the mission to Rome while Antrim was one of those chosen to go to Paris.

To counter the rise of extremism the middle group sought to increase the power of the assembly. A number of directives were issued dealing with the application of power at the highest levels. In future, the Supreme Council was to function according to the dual principles of majority rule and collective responsibility. Records of individual performances were to be kept and council members were henceforth to be directly answerable to the assembly. Steps were also taken to ensure that future elections to the assembly were to be held in secure areas where voters would be free from physical intimidation. By this move the middle group hoped to rid the assembly of ‘serving men’, or creatures of patronage, thus reducing the influence of powerful individuals. This entire package of measures displays a remarkable degree of political sophistication in a war-torn society and marks the high point not only of middle group influence, but also of the radical development of the General Assembly.

Pressure for peace

Within a few months, however, the military situation had deteriorated further, increasing the pressure for some form of peace settlement. The Supreme Council favoured a cessation of hostilities with Lord Inchiquin, the Protestant commander in Munster and a notorious enemy of the Catholic church. While such a move made sense from a military viewpoint it, not surprisingly, upset Rinuccini who fled Kilkenny and joined up with Eoghan Ruadh O’Neill. Confederate unity was irrevocably shattered along with the policy of consensus so carefully nurtured over the previous eighteen months.

Faced with the option of all out war or the possibility of a second more acceptable treaty with the royalists, the middle group reluctantly choose the latter course. The majority of confederates now favoured peace, and war party opposition to a treaty proved ineffective without middle group support.

The middle group’s final contribution to confederate politics was in the peace negotiations with the royalists. The first Ormond Peace in 1646 was more notable for its omissions than its actual provisions. All matters of religion were simply referred to ‘his Majesties gracious favour and further concessions’. The treaty contained no review of Ireland’s constitutional relationship with England, without which Irish Catholics would be vulnerable to abuses by the Dublin administration and to interference from the Puritan parliament at Westminster. Finally there was nothing in the agreement for the people of Ulster who had suffered most through the plantation process.

The second Ormond peace

The 1649 treaty, published in January, addressed each of these issues. It guaranteed the free exercise of the Catholic faith without interference from the Protestant clergy. The thorny question of church livings was to be decided at the next meeting of the Irish parliament, in which Catholics, thanks to further concessions, were likely to have a majority. This Catholic-controlled parliament would also examine the issue of Ireland’s constitutional relationship with England, including the exercise of Poynings Law, and accept petitions from Ulster for compensation for all attainders and forfeitures since 1603. As a further safeguard to Catholic interests, the confederates were to maintain a standing army of 15,000 infantry and 2,500 cavalry until the full settlement was ratified by parliament. Any attempt by royalists to renege on the agreement would be opposed by this force.

The second Ormond peace was the quintessential middle group document, a triumph of moderation and pragmatism. It was too little, too late, however. Royalist power in England had collapsed and the execution of Charles I was only weeks away. More ominously, a civil war had erupted among confederates shortly after the nuncio’s flight from Kilkenny and all semblance of unity disappeared with publication of the treaty. Rinuccini, disheartened by the failure to obtain state recognition for the Catholic church, left Ireland shortly afterwards, but his allies in the war party continued to oppose the settlement. Eoghan Ruadh O’Neill and his Ulster forces, seeking a restoration of estates, also remained alienated from Kilkenny. These divisions contributed greatly to the disasters which followed.

Ormond’s total incompetence as a military commander and political conciliator further exacerbated an already desperate situation. His defeat at Rathmines by a smaller parliamentarian force allowed Oliver Cromwell and his army, fresh from their victories in England, to land unopposed in Ireland in August 1649. The campaign which followed consisted largely of a series of sieges, with the Catholic Irish and their royalist allies constantly on the defensive. Despite the gallant defences of Waterford, Clonmel and Limerick, the forces of the New Model Army proved irresistible and the last formal surrender was taken in April 1653.

Conclusion

The ultimate failure of the confederate experiment in government, under the dual pressures of war and factional strife, should not detract from the huge strides taken in the 1640s. The unprecedented regularity of the General Assembly’s sessions and its wide geographical (if not social) representation contributed to the emergence, possibly for the first time, of a national attitude through the process of shared experience. This development was exploited by the middle group from 1646 onwards. Its policy of consensus and representative politics struck a responsive chord with the evolving desire of the assembly members for a more active role in confederate affairs. The result was a dominant and politically sophisticated assembly which must be placed very firmly in the mainstream of Irish parliamentary tradition.

Micheál Ó Siochrú is a postgraduate student at the Department of Modern History, Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

J.C. Beckett, The Making of Modern Ireland (London 1966).

Casway, Owen Roe O’Neill and the struggle for Catholic Ireland (Philadelphia 1984).

T.W. Moody, F.X. Martin & F.J. Byrne (eds.), A New History of Ireland, III 1534 -1691 (Oxford 1976).

Ohlmeyer, Civil War and Restoration in the three Stuart kingdoms (Cambridge 1993).