Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill

The 1889 Light Railway (Ireland) Act was the first to provide government grants for the construction of railways, which had previously been the domain of private enterprise. This and subsequent acts of 1890 and 1896 brought the railway to remote, thinly populated districts which were considered commercially non-viable by the railway companies. £1,553,967 was spent on the construction of fifteen separate lines. The railway companies themselves raised the extra money needed to complete the lines, supplemented by local funds. They were mostly in the distressed districts of Donegal, Mayo, Connemara and Kerry, and since the original act was passed principally through the efforts of Chief Secretary Arthur Balfour, the lines were often referred to as ‘Balfour lines’.

The Connemara line

The Connemara railway ran for over forty eight miles through some of the most breathtaking scenery Ireland has to offer, past lakes, mountains and bogs, making its way from Galway station, through the rugged grandeur of Connemara and on to the coastal terminus at Clifden. The line was welcomed by the people of Connemara as a relief from present difficulties and a guarantee against future ones. Previously all supplies to Clifden, and the surrounding villages, were delivered by sea, except for small parcels which were conveyed by cart from Galway. Consequently prices increased during winter months, and frequently bad weather created shortages.

Several previous attempts to establish a railway link between Galway and Clifden had failed due to lack of funds. During the 1880s severe weather conditions, bad harvests and a fall in agricultural prices, left the people of Connemara in very poor circumstances, and as usual in times of distress, a demand for public works was directed at government. The construction of the railway was proposed as a means of offering large-scale employment over a wide area. The railway, it was argued by community leaders, would give local produce access to outside markets. This would aid the development of fisheries and agriculture, which would in turn greatly improve the conditions of the people, thereby insuring that public works would never again be necessary. The government responded favourably and a grant of £264,000 for construction was made to the Midland Great Western Railway Company which was also to maintain and operate the line. The grant proved insufficient to complete the works and the company had to contribute an additional £146,000 and between £30,000 and £40,000 towards rolling stock.

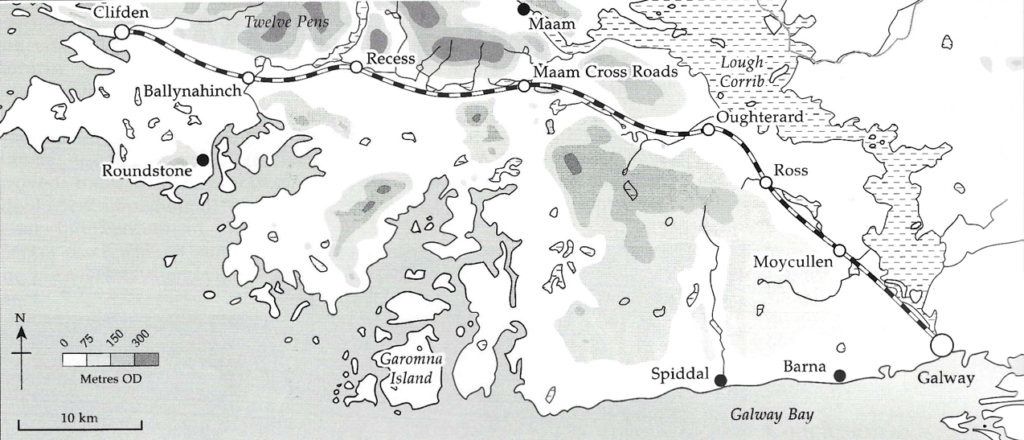

Choosing the route

Once the decision to construct had been taken, and the finances secured, disagreement broke out over the route. Galway to Oughterard was not a problem, but after that opinion was divided. The vast majority of Connemara’s 60,000 inhabitants lived along the coast. And as the railway was expected to advance the development of fisheries, many believed the line should follow a coastal route through Spiddal, Carraroe, Roundstone and on to Cliften. Great efforts were made to have this coastal route adopted. The MGWRC stated publicly that they believed this to be the best route. The Royal Commission for Irish Public Works, however, disagreed, and for reasons which were never publicly stated, favoured a direct inland route. It may well be that the offer of free land from Mr Berridge of Ballynahinch Castle, through whose estate twenty miles of track was to run, had some bearing on the decision.

Problems with contractors

As the winter of 1890 approached conditions in the West deteriorated even further. The government put pressure on the company to begin work immediately. The project was to commence as relief work and all those seeking employment were to be hired. J.H. Ryan and Townsend of Galway were employed as joint engineers by the MGWRC, and they began preparing plans and estimates. A provisional contract was drawn up with Robert Worthington, to facilitate the government’s demand for a quick start, and sections of the line were mapped out. By the end of January 1891 five hundred men were employed, cutting drains and carrying out other surface work, on the boglands of central Connemara. To accommodate this workforce, many of whom lived some distance from the works, huts were erected at various points along the line. But still the government received complaints that not enough men were being employed, They were also told that Worthington was picking and choosing his jobs. The engineers too were receiving disturbing reports regarding the quality of his work. In March 1891 one hundred men went on strike at Clifden, demanding an increase of six pence per day and a change in working hours from 6am-6pm to 7am-5pm. The average wage was twelve shillings per week. The workers’ demands were met and the strike settled almost immediately. When the final contract was put up for tender it was won by Charles Braddock. A quick hand over to the new man was urged by government so as not to leave the people without employment for any length of time.

Charles Braddock, ‘mere adventurer and pauper contractor’

Braddock promised employment for all who sought it, and by the middle of May the works were again open and hundreds of men were back working along the line. However, although Braddock was anxious to employ all who sought work, he was not as anxious to pay them. One year later, May 1892, payment of wages was said to be irregular and in some places did not take place at all. The men were to be paid fortnightly, on Fridays and Saturdays. Those from around Galway were receiving regular wages, but those at Moycullen were forced to come into the city demanding payment. They were told there was no money for them, but that as soon as some would arrive they would be paid. Workers in Oughterard took out summonses against Braddock. And in Clifden, one hundred and eighteen men went on strike at the end of May. However, following discussions they were back at work by the middle of June; but payment of wages continued to be irregular. By now Braddock had run up debts among the traders in Galway city. They complained to the company, accusing it of bringing a ‘mere adventurer and pauper contractor into the area’. But the MGWRC refused to accept responsibility for Braddock’s debts. However, on 8 July 1892, the company was forced to take action and took possession of the entire works, along with all plant and machinery, for breach of contract.

Shebeens

The contract was handed over to T.H. Faulkner who proved more successful then his predecessor. It was originally planned that the line would open in December 1893, but this was now out of the question. Extra time for completion was sought on two occasions from the privy council. As work progressed there were over 1,000 men employed along the line, rising to a peak of 1,500 by November 1893. Skilled men were brought in from the outside, but all labouring work was carried out by men from the locality. To facilitate such a large workforce in the wilderness of Connemara, the contractor opened a provisions shop in a number of huts at Ballinafad. This store was of great benefit not only to the labourers but also to the locals, many of whom travelled long distances to purchase provisions. A number of unsavoury characters were also attracted into the area. Shebeens were set up along the line and the local priest complained of the ill-effect the sale of illicit alcohol was having on his parishioners. The contractor too was suffering the ill-effects of poteen being readily available. Attempts were made by the contractor, and the priest, to have the sheebeens closed down, but without success. It wasn’t until the works were completed and the men had left the district, that, much to the disappointment of the locals, the shebeens and the store were closed.

The opening

The line between Galway and Oughterard was opened on New Year’s Day 1895. A special train left Galway on the Tuesday morning at 8am. On board were Joseph Tatlow, the manager of the MGWRC, and other dignitaries. They arrived at Oughterard at 9.15am. At Oughterard the train took on seven passengers and left at 9.25. Five passengers were picked up at Moycullen, and the train arrived back in Galway at 10.18am. The explanation given for such a small number of passengers was that New Year’s Day was a strict church holiday and people were obliged to stay home. After returning from Oughterard, Tatlow liberally entertained several gentlemen in the Railway Hotel in Eyre Square. The train again departed for Oughterard at 10.45am, this time with considerably more passengers on board. The remainder of the route was opened with very little ceremony on 1 July of the same year. The line had taken five years to construct at a cost of £9,000 per mile, at a time when the average cost per mile of light railway was between £3,000 and £5,000. Two trains each way, each day, were planned for the route.

The route

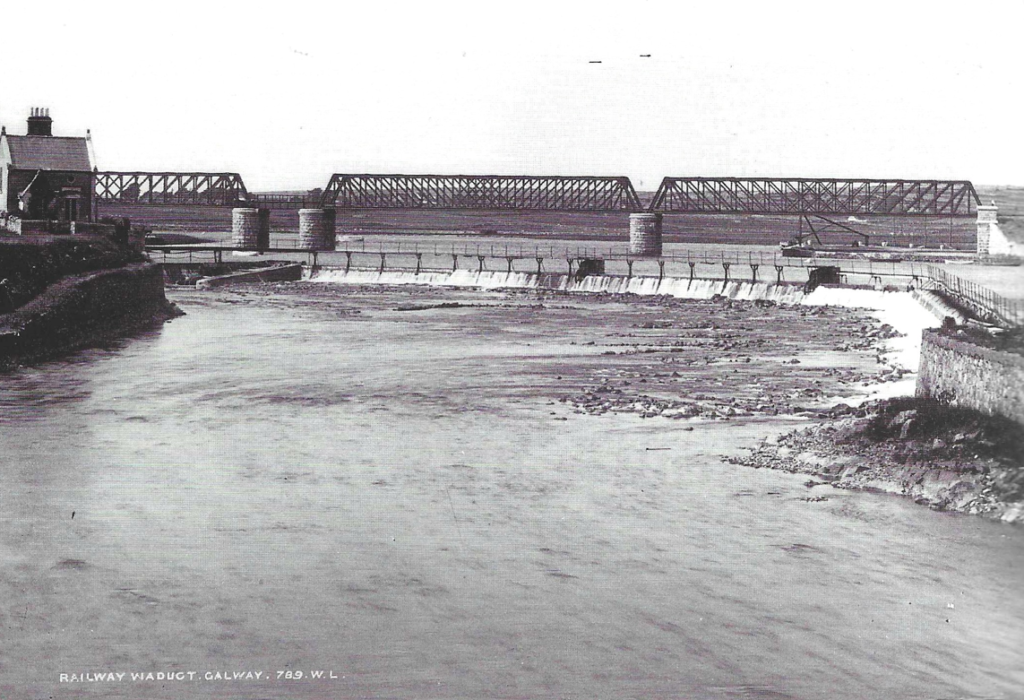

The total length of the line was forty-eight miles 550 feet. It was a single line with a broad gauge. There were seven stations, seven to eight miles apart and and four–Moycullen, Oughterard, Maam Cross and Recess–had passing places or loops, with up and down platforms. Leaving Galway the line passed through the only tunnel, described by the engineers as a ‘cut and cover’ which carried Prospect Hill roadway over the railway, then through the outskirts of the city to the Corrib river. The river was crossed by a viaduct, ‘an imposing and elegant structure of steel’, with three spans, each of 150 feet, and a lifting span of twenty-one feet, to allow for navigation of the river. Once over the bridge the line ran for miles along the west side of the river and the western shore of Lough Corrib, ‘passing deserted mansions, breweries and factories’. The first station was Moycullen, then Ross and Oughterard. From there the line ran west through the heart of Connemara stopping at Maam Cross and Recess. Here the railway met with Alexander Nimmo’s link roads, laid out some seventy years before, which cut through the passes of Maam and Inagh Valley, linking Westport, Killery Harbour, Kylemore and Letterfrack to the north, with Screeb, Casla and Cashel to the south.

After Recess the line passed the southern shores of Derryclare and the eastern end of Ballynahinch lakes before moving on to Ballynahinch station. Ballynahinch was expected to receive a good deal of tourist trade from anglers visiting the lakes. And fish from Roundstone would be exported from here. After Ballynahinch the train passed through a ‘long stretch of wild and rugged country, interspersed with many lakes, before reaching the terminus at Clifden’.

There were twenty-eight bridges on the line, with thirteen other ‘small accommodation‘ bridges. There were eighteen gatekeeper houses erected at public road level crossings. Limestone, from the many quarries between Galway and Oughterard, was used in the construction of the stations. Where local stone was unworkable red brick was used. The stations were roofed with red tiles and were described in the engineer’s report as having a ‘picturesque appearance’, and ‘may strike the tourist as being more elaborate than the generally wild surroundings would warrant’.

Promoting tourism in Connemara

The government hoped that the construction of the line would help develop the fisheries and other local industry. However, the MGWRC believed that it would take years for the line to pay and that its principal trade would be tourism. To this end the company set about promoting Connemara. Tourist handbooks regularly appeared carrying picturesque descriptions of the many attractions Connemara had to offer the angler and tourist. Accommodation and prices were listed, with maps and suggested routes through the mountain passes provided.

In 1903 the company laid on a special tourist train which ran daily from Dublin to Clifden during the summer months. It had a dining car, and stopped at Mullingar, Athlone, Athenry, Galway and Oughterard. To facilitate the tourist traffic, touring cars linked Clifden station with Westport station, taking the traveller through the Connemara mountains and along Killery Harbour en route.

The company built a hotel at Recess, where King Edward VII and his party lunched in July 1903, during his tour of the congested districts of the West. Over the years the company advertising paid off, and the rich and famous came to Connemara to shoot and fish. Fishing lodges were built by English and Irish gentlemen, and Connemara developed a reputation as a popular holiday destination for the upper classes. However, for most of the people of Connemara the railway was simply the first stage in that long emigrant trail which would carry them halfway across the world.

Closure

In time the line passed to the ownership of the Great Southern Railway Company. By the 1930s it was in bad repair and doomed to closure. The company argued that the huge cost for repairs could not be guaranteed by an increase in traffic: the increase in private motor car ownership and the availability of private road haulage were proving too stiff a competition for the company. On Saturday 27 April 1935 the last passenger train pulled out of Clifden. The whistle blew and detonators were fired at every level crossing, and groups of people gathered along the route to bid it farewell. At each station old wagons were hitched on, making the last train from Connemara very long and important looking as it entered Galway station.

The railway was replaced by a fleet of buses and lorries, and the roads were tarred in preparation for the service. Local opposition to the closure was strong, but the company pointed out the advantages of the new service. Goods would now be delivered directly to homes and shops, and the bus would stop on request along the route from Galway to Clifden. A daily service between Clifden and Roundstone was soon to come into operation. In time the tracks were removed and sold to a German scrap company, and, local folklore has it, were later used as bombs against Britain during the second world war.

Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill is a local historian.

Further reading:

J.H. Ryan, ‘The Galway to Clifden Railway’, report of the Civil Engineers of Ireland (Dublin 1902).

J. Tatlow, ‘Fifty Years of Railway Life’ in Railway Gazette (Dublin 1920).

K. Villiers-Tuthill, Beyond the Twelve Bens (Galway 1986).