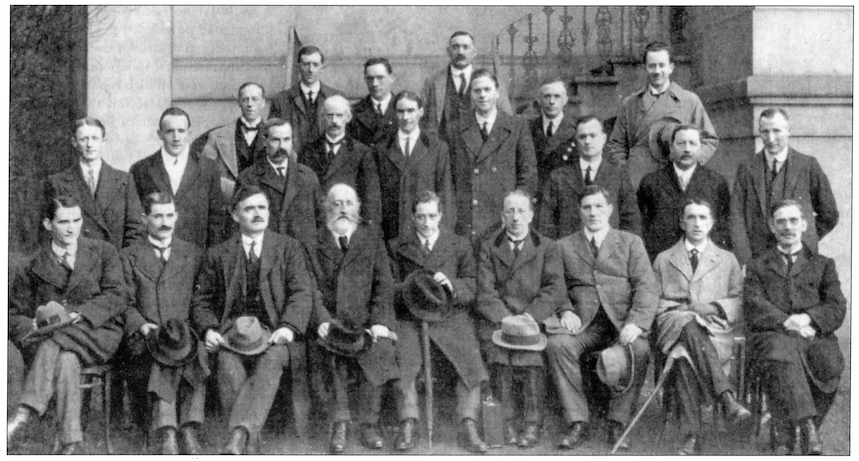

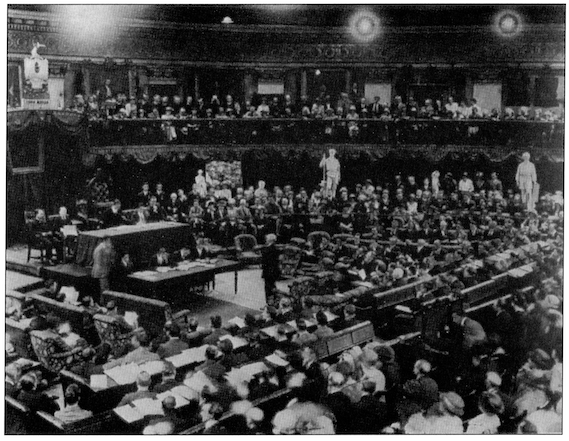

January 1919. Seated from left’.J. O’Doherty,

S. Hayes,J.J. O’Kelly, Count Plunkett,

C. Brugha, S.T. O’Kelly, P.O’Malley,

JJ. Walsh, T. O’Kelly, Standing from left:

S. MacSwiney, K.O’Higgins, R. Barton,

D. Buckley, R. Mulcahy, E. Duggan,

C. Collins, P. Beazley, P. Shanahan,

Dr. J. Ryan, Dr Crowley, P. Ward,

J.A. Burke, P.J. Maloney, R. Sweetman.

1916 after 1916

The 1916 Rising and its aftermath redefined the Irish nationalist movement. New parties and new names emerged and in June 1917 a provisional committee was formed to draw up a new Sinn Féin constitution. Apart from Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin and the IRB, the other bodies were all new: the Liberty Clubs (Volunteers), the Irish Nation League, the Mansion House Committee and the Released Prisoners Organisation. Following Count Plunkett’s election victory at Roscommon on 5 February 1917, most of these groups had already been in contact with each other. Plunkett stood for the ideals of 1916 and for abstention from Westminster. He was supported by Cathal Brugha who held a leading position in the revived Volunteers or Liberty Clubs, which were republican in principle. Griffith’s Sinn Féin was still committed to the ideal of the ‘King, Lords and Commons of Ireland’. The Irish Nation League was made up of former members of the Irish Party who were opposed to any Home Rule solution involving partition. Their aspirations and attitudes were effectively summed up by Thomas Kettle, who died in the Somme in 1916, but who, in reply to Kipling, had written:

Ulster is ours, not yours, Is ours to have and hold.

Our hills and lakes and moors Have shaped her in our mould.

Derry to Limerick Walls

Fused us in battle flame; Limerick to Derry calls

One strong-shared Irish name.

The same sentiments were shared by all the groups which combined to form the new Sinn Féin. The Mansion House Committee, set up on 19 April 1917, was a composite body of all groups together with representation from the Labour Party. The last group, the released prisoners organisation, had a significant IRE representation.

(Courtesy of National Library of Ireland)

The new Sinn Féin

A unified declaration of purpose was agreed at the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis of 25–26 October 1917. The elected delegates viewed themselves as ‘representatives of the Irish people’—a type of assembly that foreshadowed the Dail itself. Inspired by the Proclamation of 1916, they declared following pithy verdict on the 1917 Sinn Féin constitution and the people involved:

that the aim of the new Sinn Féin was to secure ‘the international recognition of Ireland as an independent Irish Republic’. ‘Having achieved that status’, it was added, ‘the Irish people may by referendum freely choose their own form of government.’ This clause was an indication that all issues had not been absolutely resolved. It was reported that ‘de Valera had found a formula to satisfy Brugha (who wanted a clear cut declaration for the Republic) and Griffith (who had been insisting on the old Sinn Féin programme)’. In his summing up of the Sinn Féin funds case in 1948, Judge Kingsmill Moore gave the

The desire to obtain the maximum amount of independence which it was possible to win formed the real bond between all members of the new national Sinn Féin, not any hard and fast adherence to a Republican ideal. To some who held what I may call the transcendental view, the Republic was an article of faith; others considered that at that juncture in world affairs there were sober and valid reasons for thinking that an independent republic could be obtained; still others – and these perhaps a majority – regarded the republic only as the best and most dramatic symbol of independence; a few accepted it cynically as a convenient piece of political clap trap.

These differences were not to the fore in October 1917. The ordinary member of Sinn Féin and the ordinary person who voted for them did so because, again in the words of Kingsmill Moore,

for them the Republic was a battle cry, a symbol, an evocative word of immense power. It released a long suppressed desire for national realisation, national independence…the institution of an Irish republic, if possible and practical, was the simplest and most immediate way of achieving his desires.

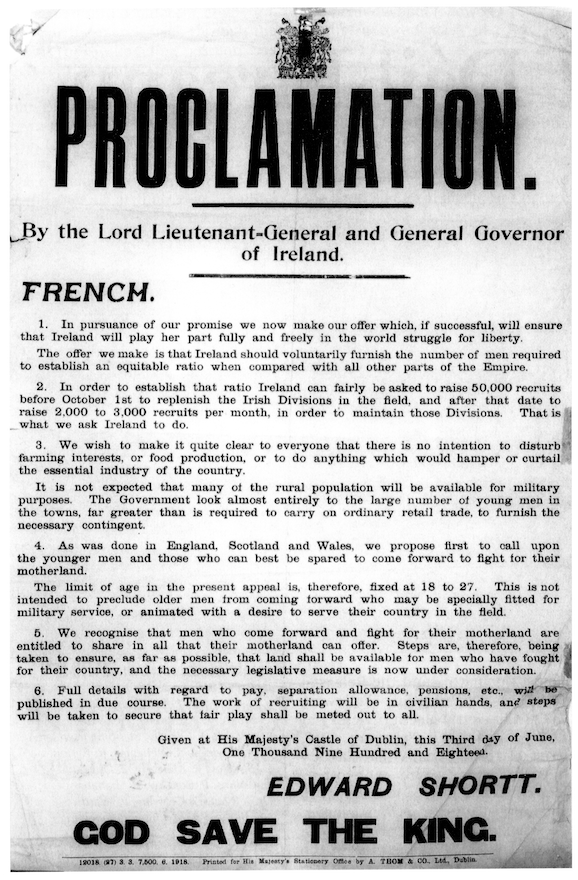

The Anti-Conscription Campaign

The major event that inspired the Sinn Féin organisation in 1918 and which brought many into its ranks was the anti-conscription campaign. The Catholic Church, the Irish Party, the Labour Party and Sinn Féin were united in their opposition to conscription; many drew the conclusion that only an independent Irish parliament on the Sinn Féin model would prevent Irishmen being called up by a British parliament to fight British wars. There was a striking growth in membership of nationalist organisations: Sinn Féin had 1,300 registered clubs with a membership of 250,000 by the end of 1917; the Gaelic League also expanded from 312 branches in 1917 to 700 by 1920; and the membership of the Irish Volunteers and the IRB also grew. The popular base existed to conduct an election campaign and from May 1918 a standing committee of Sinn Féin began planning an election strategy. Despite the difficulties created by the arrest of leading figures, the election campaign ran smoothly. A new impetus, almost a new direction, was given to it by the announcement of the end of the World War on 11 November 1918.

Self-determination

The principle of self-determination came to dominate all political discussion. Self-determination had been an explicit or implicit aim behind Irish nationalist appeals for help after 1916: it was, after all, the basic demand of the separatist ideal. Patrick McCartan, acting as envoy of the Irish Republic, presented such an appeal to US President Wilson on 18 June 1917. A year later, almost to the day, 11 June 1918, a national appeal had been made by all parties to protest against conscription. It was pointed out that Britain refused to acknowledge Ireland’s national rights; ‘yet while self-determination is refused, we are required by law to bleed to “make the world safe for democracy” in every country except our own’. The ending of the war gave renewed prominence to this issue.

It had an immediate and important effect on Labour Party policy. Labour leaders advised their members that the transition from a ‘war election’ to a ‘peace election’ forced them to reconsider their position. As national issues were to be the principal items on the peace conference agenda, it was suggested that they should withdraw from the election to allow ‘a clear expression of the people’s opinion upon the question of self-determination’. The withdrawal of Labour advanced the cause of Sinn Féin.

By chance a meeting of the Sinn Féin party had been called for 11 November to launch the election campaign. News of the peace changed their plans. The presiding officer announced that not only was he opening the election campaign, but he was also proposing a declaration of Ireland’s independence. Other speakers took up the theme; Sean T. O’Kelly declared that they would approach the Versailles peace conference and demand that President Wilson apply his principles of freedom to small nations to Ireland; Eoin MacNeill proclaimed that ‘England could not apply self-determination to Ireland, the Irish must do that for themselves’. These sentiments were contained in the subsequent election manifesto and provoked a police raid on Sinn Fein headquarters on 20 November. Copies of the offending manifesto were seized and subjected to censorship. Nevertheless, the appeal of Sinn Féin and of self-determination carried the day. When the election results were announced on 28 December, it was evident that Sinn Féin had replaced the Irish Party as the largest party in Irish politics.

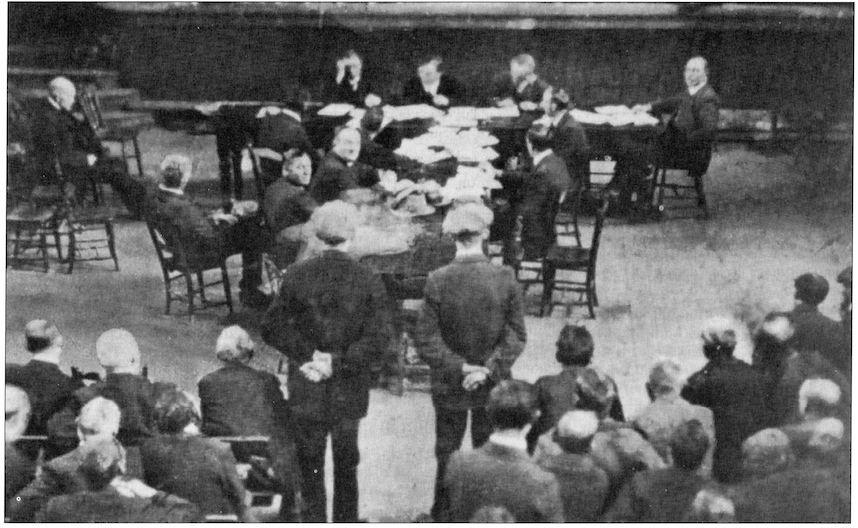

Dail court at Westport, County Mayo.

Dáil Éireann

Sinn Féin’s representation jumped from seven to seventy-three seats; the Irish Party’s collapsed from sixty eight to six; the Unionists increased their total from nineteen to twenty six. The franchise for the election had been greatly enlarged by the Representation of the People Act of 1918: in 1910, 701,475 were on the register; in 1918, 1,936,673. This increase in votes enabled the Irish Party, strangely enough, to retain its following in most constituencies but prevented it from securing its former seats. The transition from Sinn Féin to Dáil Éireann was efficiently arranged. Even before the results were announced, the Executive Committee of Sinn Féin met on 19 December and ‘decided to convoke Dáil Éireann’. Meetings were planned for 1 and 2 January. While Sinn Féin was central to the establishment of the Dáil, there was recognition that the new body was to have a distinct and separate character. Members elected to parliament were referred to as the ‘elected Republican members’ and they were to meet alone on 2 January. Moreover, ‘it was decided to refer to the Dáil Éireann the question of its machinery and functions, and the future relations between it and the Standing Committee’. At these meetings held over the following weeks, the declarations and principles that were to colour the character of the first Dáil were agreed.

For the most part, the proceedings of the first Dáil on 21 January 1919 were conducted in Irish, beginning with a prayer delivered by Fr Michael O’Flanagan. The initial business was conducted swiftly: the appointment of a speaker, Cathal Brugha, the appointment of clerks, and the calling of the roll. Twenty-nine names were recorded as present, but the attendance of Boland and Collins was incorrectly called to conceal their mission to rescue de Valera from jail. Then the main resolutions of the assembly were formulated: the constitution, the declaration of independence, the address to the free nations of the world, and the democratic programme. The first was read in Irish alone; the other three in Irish, French and English.

No oath was administered on 21 January. A republican pledge had been signed at a meeting on 7 January by the elected deputies present:

I hereby pledge myself to work for the establishment of an independent Irish republic; that I will accept nothing less than complete separation from England in settlement of Ireland’s claims; and that I will abstain from attending the English Parliament.

There was no formal oath applied to members until the proposal by Cathal Brugha, seconded by Terence MacSwiney, on 20 August 1919 containing the words:

I will support and defend the Irish Republic and the Government of the Irish Republic, which is Dáil Éireann, against all enemies, foreign and domestic…

Brugha wanted the oath applied to deputies and officials of the Dáil, and to the Irish Volunteers (Irish Republican Army). Some deputies expressed caveats but most were in favour, including Arthur Griffith, and the motion was passed. The IRA was now subordinate to Dáil Éireann; the political and military struggle against British rule was thus unified and the scene was set for the War of Independence.

Self-determination in practice

The promised era of self-determination that had been welcomed in the message to the free nations of the world and the ideals of the declaration of independence constituted the main political aim of Dáil Éireann, the recognition of the independent Irish Republic. It sought to vindicate that claim on both the national and international plane. At home the Dáil served as a source of authority not only to give expression to the will of the people, but also (after April 1919) to command the allegiance of the army. This manifestation of principle was matched by a concern for practical affairs: the Government of the Republic did actually attempt to govern. For example, Michael Collins, at the department of Finance, raised loans for the Republic most effectively; the republican courts operated in many parts of the country; envoys and trade consuls were appointed to act in America and in the major countries of Europe; initiatives were taken in regard to the land, the setting up of a land bank, and developing cooperative societies. These activities were maintained even after the proscription of Dáil Éireann on 10 September 1919, along with Sinn Féin, the Gaelic League, the Irish Volunteers and Cumann na mBann. All these activities were ultimately designed to strengthen Ireland’s claim to recognition.

More explicit appeals for recognition (and money) were made by de Valera in America after his departure in June 1919. In his absence two local-government elections were held: municipal elections in January 1920 and rural elections in June. The results confirmed and even strengthened the popular mandate given in the 1918 general election. On 27 October 1920, de Valera presented a memorandum to the government of the United States entitled ‘Ireland’s Claim for Recognition as a Sovereign Independent State’ in which he stressed that the Dáil was in many ways acting as the government of the country, and that this right to govern was justified by a democratic mandate. British military power, he contended, was solely responsible for preventing the working of the democratic process. Referring to the electoral mandate in three elections, he concluded:

To repudiate the evidence of the ballot, the most civilised method of declaring the national will, and to demand that, as a condition of recognition, the bullet be more effectively used, is to introduce into international relations an inhuman principle of immorality. Ireland’s claim today,

measured by all the moral and legal standards the United States has established since its infancy and measured by the moral principles upon which the greatest war in history was fought, is as strong as any additional bloodshed can make it. Further bloodshed would not more decisively prove the national will of the people of Ireland, but a refusal of recognition now would invite it.

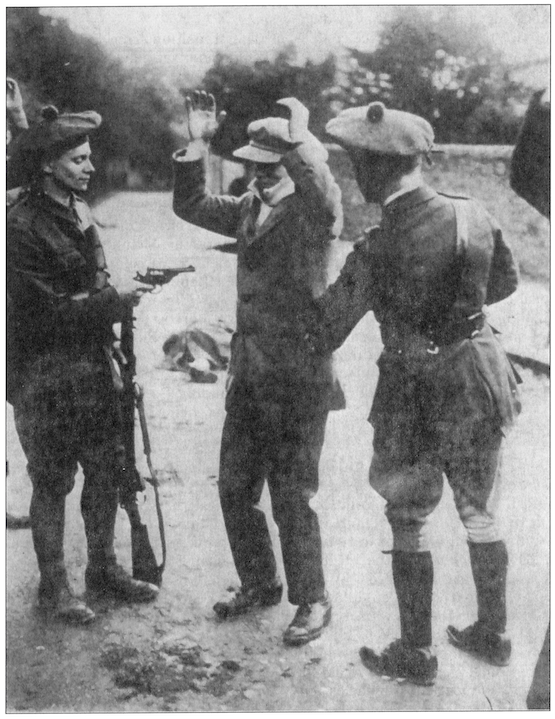

The British response

The British, meanwhile, sought to destroy the Dáil’s influence, not only by banning it (September 1919), but also by measures which advanced on two fronts: on the one hand a military campaign was conducted to suppress the Republic; on the other hand, a constitutional process was initiated to subvert it. On the constitutional front, the main driving force was the Irish Committee of the British Cabinet, newly re-created in October 1919 and heavily under Unionist influence, notably through Sir Waiter Long. The Government of Ireland Act of 23 December 1920 was the result. Members of the Dáil were slow to realise the full implications of the Act, which dealt a severe blow to the Dáil’s battle for self-determination. The unity of Ireland was denied and the sovereignty of Britain was asserted not only in Northern Ireland, but also over Ireland as a whole.

De Valera arrived back in Ireland as the Act was passed. By this time the British had adopted another tactic. Since about October 1920 secret negotiations had begun with leading Sinn Féiners and members of Dáil Éireann. War and secret negotiations existed side by side until the truce of 11 July 1921. In the meantime the Government of Ireland Act had been implemented in the north and its separate parliament was inaugurated on 7 June and publicly opened by the king on 22 June. This development gravely weakened de Valera’s negotiating position as he visited Lioyd George in London to argue for Ireland’s unity and self-determination on 14 July 1921. Moreover the very position of the first Dan was in some doubt.

Only four private meetings of Dáil Éireann were held after de Valera’s return from America. At the meeting of the Dáil on 10 May, de Valera had proposed that ‘the parliamentary elections which are to take place during the present month be regarded as elections to Dáil Éireann’. Sinn Fein members were returned unopposed in constituencies outside Northern Ireland. De Valera also proposed that the ‘present Dáil dissolve automatically as soon as the new body has been summoned’ and that ‘the Ministry remain in power until the new Dáil has met’. De Valera did not summon the second Dáil until 16 August. From 13 May until 16 August, therefore, the affairs of Ireland were in the hands of de Valera and the ministry of the first Dáil.

Dublin, August 1921.

The second Dáil

The second Dáil met on 16 August 1921 and the members—all returned unopposed—publicly took the oath to preserve the Republic. They unanimously rejected Lloyd George’s offer of dominion status, which declared that Ireland’s right ‘to secede from her allegiance to the King’ could never ‘be acknowledged by us’. De Valera informed Lloyd George on 24 August of the Dáil’s decision and added ‘we have not sought war nor do we seek war, but if war would be made upon us we must defend ourselves, and shall do so’. It would be hard to find a more forceful assertion of the principles which had been enunciated at the first meeting of the Dáil on 21 January 1919.

Ironically while the Dáil changed its constitution to make de Valera formally ‘President of the Republic’, instead of ‘President of Dáil Éireann’, the Republic was more under threat than ever. De Valera’s replies to Lloyd George could not be construed as an abandonment of the republican position, but his introductory remarks to the Second Dáil on 16 August raised some doubts. Reflecting on the origins of the Dáil, he referred to the general election of 1918 which had brought Sinn Féin to power:

I do not say that that answer was for a form of government so much, because we are not republican doctrinaires, but it was for Irish freedom and Irish independence, and it was obvious to everyone who considered the question that Irish independence could not be realised at the present time in any other way so suitably as through a republic.

De Valera maintained that in 1919 ‘the first duty, therefore, of the ministry was to set about making that de jure Republic a de facto Republic’. In 1921 that proved impossible. Negotiation, and the compromise attendant on it, exposed the differences in approach that had brought many into the Sinn Féin movement.

The principles of the first Dáil and the unity of its members were lost as first the cabinet (8 December 1921) and then the Deiil (7 January 1922) split over the Treaty proposals. The rending of Irish unity and the abandonment of republican ideals was marked most dramatically by the meeting of the pro-treaty group as ‘the parliament of Southern Ireland’ on 14 January in order to ratify the Treaty. Their action recognised the British claim that Dáil Éireann was not a lawful authority; simultaneously the Provisional Government was created. Acting in co-operation with the British government, this prevented the second Dáil from dissolving itself, thus giving rise to the question of the lawful lineage of the republican Dáil. The unity of Sinn Féin was also destroyed. After two Ard Fheisenna in 1922, Sinn Féin as ‘a band of brothers’, committed to its 1917 constitution, was no more.

Conclusion

A partial explanation for the failure to secure the republican ideal has been provided by the judgement of both Fr Michael O’Flanagan and Kingsmill Moore that not all those who joined Sinn Féin in 1917 were committed republicans. The Treaty debates accentuated this inherent division. Treaty supporters maintained that the political impetus after 1916 was to secure the maximum measure of freedom and independence and not a republic; Treaty opponents spoke for the Republic pure and simple. However, this focus on inherent division within Irish ranks misses an additional important point: the role of the British government in creating that division in the first place. Kingsmill Moore shrewdly observed that:

If [in 1921] England had offered a little more or a little less, there would have been unanimity in acceptance or rejection, but the English terms were exactly…of such a nature as to reveal and accentuate some of the most fundamental divisions in human temperaments.

British proposals in regard to the Government of Ireland Act and the Treaty not only revealed divisions amongst the Irish people, but also caused and accentuated them.

Brian Murphy is author of Patrick Pearse and the lost Republican ideal (Dublin 1991).

Further reading:

B. Farrell, The founding of Dáil Eireann (Dublin 1971).

D. Carroll, They have fooled you again – Michael O’Flanagan 1872-1942: priest, republican, social critic (Dublin 1993).

S. Ó Riain, ‘Dail Eireann 1919’ in Capuchin Annual (1969).

N. Mansergh, The unresolved question: the Anglo-Irish settlement and its undoing 1912-1972 (Yale 1991)