The Wexford lockout was not merely a struggle between employers and workers; it also brought into sharp focus the visceral opposition of the Catholic Church to trade unionism in Ireland, the violent approach taken by the police authorities towards ordinary workers in the town and the distance between urban workers and their national representatives, the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), who were safely ensconced over in Westminster. The struggle was not over pay or conditions; rather it was over the right of workers to combine under the banner of the Larkinite vehicle the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). This lockout was the biggest and most volatile since disturbances in Belfast in 1907 and was only eclipsed in size by the events in Dublin in 1913.

Larkin and the ITGWU

Industrial unrest in Europe, and particularly in Britain, had its own impact. The geographical location of the town meant that there were regular sailings to Wales and Liverpool, and news of industrial strife was obtained either from brief articles in the local newspapers or from the first-hand accounts of seasonal migrants. What workers took most notice of, however, was the inception of James Larkin’s ITGWU. Larkin offered the idea of one all-embracing union for skilled and unskilled workers.

Larkin launched his newspaper, the Irish Worker, in June 1911, and its circulation grew rapidly. It carried news of the union’s activities in Dundalk in August, and the ITGWU, along with Larkin’s strong personality, attracted much interest. When the ITGWU offices opened in Charlotte Street in Wexford town that month, working men promptly attended to sign up for membership. For employers, this represented a direct challenge. What concerned them most was the Larkinite tactic of syndicalism, essentially giving the ITGWU the potential to sabotage employer hegemony and disturb trade in the town. Larkin’s union had to be destroyed in its embryo stage in Wexford.

For the workers, the idea of combining the skilled and unskilled gave them both a sense of protection and a fraternal identity. Local government nurtured councillors with links and sympathies to the IPP, but the national party had done little to help improve the squalid conditions in which many workers and their families lived. Beyond the creaking goal of Home Rule, it had little in its programme for urban workers in Wexford. As the vast majority of workers had no vote for national candidates until the Reform Act of 1918, the ITGWU was identified as the vehicle that could best serve the interests of the workers. Larkin and his leadership were closer to the workers in mannerisms and attitudes; many were tradesmen or dock workers themselves. Unlike John Redmond, the IPP leader, they were not hewn from the oak of Clongowes Wood College or other similar institutions, whose students were groomed for participation in the imperial civil service. The ITGWU appeared the agency that best represented Irish urban workers. Rather than demanding improvements in pay or work conditions, what the Wexford workers wanted was the right to combine.

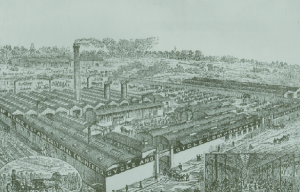

As Wexford town workers enlisted in the ITGWU, it was the foundry employers who took the decisive action of refusing to allow union members entry into their plants. Doyle’s Selskar Ironworks were the first to lock out their men on Monday 10 August 1911. A little over a fortnight later, Pierce’s locked out close to 400 men, while the Hearns, proprietors of Wexford Engineering, locked out nearly 200 men on 29 August. The actions of the foundries during this month encouraged other employers to follow suit. Thompson Engineering refused to accept ITGWU men onto their floor, while the town mayor, Howard Rowe, owner of a flour mill on Spawell Road, did the same. Almost 700 foundry men alone were out of work, which had a direct impact on the lives of over 3,000 townspeople. The employers had shown their strength and had drawn clear demarcation lines. The ITGWU was not welcome in Wexford. With no alternative source of income, the workers could only stay out for a short time before necessity would force a humble return, minus any union card.

Violence

P.T. Daly was the ITGWU agent who was dispatched to rally the Wexford workers. Arriving on 21 August, his task was to convince the workers of their right to combine while at the same time to assure them of financial aid from union funds. Daly regularly addressed large gatherings of locked-out workers in the Faythe area in the southern part of the town, and as he stirred their passions the resulting mood convinced the local RIC superintendent to draft in extra police from counties Tipperary, Waterford, Carlow and Kilkenny. These extra RIC men were tasked with escorting the blackleg workers who were recruited by the employers to fill the jobs of the locked-out local men to and from the foundries each day.

This hard-line approach taken by the employers and visibly supported by the police authorities infuriated Daly and the workers. Violence was inevitable. The initial anger of the workers was directed towards the RIC and the management of the foundries. When 150 extra police arrived in September, they were greeted by a jeering crowd and a volley of stones. A baton charge immediately followed, and fighting spread to Gibson Street and Allen Street. RIC men who tried to make arrests were quickly attacked and mauled by irate workers. Some policemen took to hiding in local shops to avoid personal injury. Even local women joined in the violence, the entertainment being to forcibly relieve a constable of his hat and baton. In these early confrontations over twenty civilians were injured. Some required surgery; James Bolger was tended in his home by Dr Hadden, as the severity of his injuries prevented his removal to the infirmary. Patrick O’Connor underwent a life-saving operation for a fracture to his skull. Over the course of the dispute, middle management of the foundries were often attacked, as they helped to ensure that blacklegs manufactured orders and as such undermined the local skilled men. Attacks included being assaulted on the way home from work, being intimidated by lurking groups of men or having the windows of their home smashed. One such figure, John Keating, had to watch helplessly from his house as angry workers burned his effigy outside. The RIC regularly arrested workers who heckled or intimidated; the offender was usually allowed home after a night in a cell.

The most serious incident occurred in September, when Michael O’Leary, on his way to buy groceries, got caught up in a baton charge on Bride Street between workers and the police. He received repeated blows to his head and died from his injuries five days later. In an inquiry into O’Leary’s death, it was discovered that Thomas Whitney, an eight-year-old boy, had also been struck on the head with a baton. The polarising impact of the lockout was made even clearer in November, when the union representative P.T. Daly was set upon and assaulted by a local businessman, Robert Belton. Requiring medical treatment, Daly went to the local infirmary, where the medical staff refused to treat him. Belton was subsequently fined by the courts for his actions.

The workers were continuously antagonised by the presence of blacklegs in their town. While some of these men were recruited from nearby rural areas of Bridgetown and Curracloe, others were brought down from Dublin and Carlow. More came from Scotland, Manchester, Leeds and the greater Birmingham area. The determination of the employers manifested itself in the placing of attractive advertisements for skilled tradesmen in English newspapers such as the Yorkshire Post. The wages offered to these men were higher than those previously paid to the Wexford skilled tradesmen. In addition, the Pierce Company accommodated blacklegs in a property they owned on the South Main Street. As they were based in the town itself, the blacklegs proved to be a provocative presence and did little to temper agitation. As the threat of poverty loomed for the workers, the mood remained black throughout the winter.

Settlement

With the imprisonment of P.T. Daly in January 1912 upon being convicted of intent to incite a riot, it was possible for the employers to sense victory. James Connolly arrived in the town in early February and stayed in the home of Richard Corish in William Street, where he tried to find a settlement. Corish was a fitter from Wexford Engineering and a committed socialist. Active during the lockout in fund-raising and cajoling men, he was also earlier arrested by the RIC for harassing blacklegs. It was from Corish that Connolly learned the mood of the men and the different views in the town. Within two weeks of Connolly’s arrival a settlement was achieved.

Connolly is often lauded for bringing the dispute to an end, but although his presence was more agreeable to the employers than that of Daly or Larkin, other factors are revealing. The tactic of using blacklegs was failing; many men brought to the town, particularly from England, were uncomfortable about depriving locked-out tradesmen of their income. The atmosphere was tense and intimidation was a daily occurrence. Departures led to a constant interruption in the manufacturing process. In addition, spring was the busiest season for the foundries, with large orders for agricultural machinery to be filled. Fearing the loss of business to foreign competition, the employers put profit before pride.

The settlement allowed for the formation of the Irish Foundry Workers’ Union as an associate of the ITGWU. The foundry men, skilled and unskilled, could combine and return to work—all except for Richard Corish, who was blacklisted by the employers on account of his efforts during the lockout. Corish appears to have been the sacrificial lamb necessary to achieve the compromise. His career as a skilled tradesman was over and instead he took up the job of secretary of the Irish Foundry Workers’ Union, albeit without a regular income.

A victory celebration was held in the Faythe on the night of 17 February and over 5,000 people gathered to cheer James Connolly and the steadfastness of the workers. The victory may not have appeared large to the neutral observer, but what it symbolised was something of great significance. The voices of the Wexford foundry men were heard despite the objections from the pulpit, the wielded baton, the political cold shoulders and the alien scabs. The Wexford lockout marked a victory for workers over the established pillars of Irish society. HI

Kieran S. Roche teaches history in St Gerard’s School, Bray, Co. Wicklow.

Read More : Condemnation and support

Further reading

M. Enright, Men of iron: Wexford foundry disputes 1890 and 1911 (Wexford, 1987).

C.D. Greaves, The Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union: the formative years (Dublin, 1982).

M. Potter, The municipal revolution in Ireland: a handbook of urban government in Ireland since 1800 (Dublin, 2011).

K.S. Roche, Richard Corish—a biography (Dublin, 2012).