By Jack Traynor

In February 1933 Eoin O’Duffy was sacked as Garda Commissioner by Éamon de Valera. Turfed out of the Phoenix Park depot and deprived of his former privileges, O’Duffy became a private citizen after eleven years in the high-powered role. He was soon sucked into the vortex of politics, becoming leader of the Blueshirts in July. The Blueshirts’ new chief embarked on a barnstorming tour across Ireland but was often met with stiff resistance. The role of his private driver became an important one. It required someone loyal, hardy and capable of doubling as a bodyguard in times of trouble. In the 1930s O’Duffy was known to have had two drivers: Robert Butler and Thomas Jolly. Their lives illustrate the twists and turns of involvement in the short-lived Blueshirts, which some feared would shake the foundations of Irish democracy.

ROBERT BUTLER

Robert Butler was born in 1906 in Cashel, Co. Tipperary. He began his career with a local engineering firm in 1923, followed by a two-year stint in the army, beginning in 1924. In 1931 he worked as driver to Dean Innocent Ryan of Cashel. In 1932 he joined the Army Comrades Association (popularly known as the ‘Blueshirts’ from April 1933 onwards).

On 22 August 1933 the Fianna Fáil government banned the Blueshirts, on foot of a ban a week earlier of a planned march to Leinster Lawn. By September the anti-Fianna Fáil opposition, composed of Cumann na nGaedheal, the Blueshirts and the National Centre Party, had merged to form Fine Gael, with O’Duffy as its inaugural leader.

Autumn 1933 saw violent clashes nationwide between Blueshirts and republicans. Butler and another Blueshirt were alleged to have assaulted a local Cashel republican, John Cullagh, in September. By then Butler seems to have been employed by O’Duffy as his personal chauffeur. He moved in with the general at his address at ‘Farney’, in the south Dublin suburb of Greygates, Mount Merrion. On 6 October O’Duffy was driven from Limerick to a public meeting in Tralee in a three-car convoy. On the way, a local IRA unit (including future Labour TD Stephen Coughlan) unsuccessfully tried to shoot O’Duffy but failed to pick out his car from the convoy. The Tralee meeting itself descended into violence. The hall was besieged, windows were broken and an unexploded bomb was thrown into the hall. O’Duffy was struck on the head with a hammer. His car was then stolen and set on fire. Butler made a deposition to a commission set up to investigate the alleged inactivity of the Gardaí during the incident.

O’Duffy’s political career nosedived in September 1934 following a split inside the Blueshirts and Fine Gael over his increasingly erratic and extreme style of leadership. In the minority, Butler remained loyal to O’Duffy and continued to act as his driver. When O’Duffy announced the formation of an Irish brigade to fight for the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War, Robert Butler and his elder brother William were early recruits. They departed for Spain via Liverpool in November 1936. In February 1937 William Butler wrote to his mother, claiming that among the Irishmen ‘there is an unwavering belief in the certainty of the Spanish insurgents’ triumph over the forces of Anarchy and Communism’.

Following his return from Spain in June 1937, Robert Butler continued to live with O’Duffy despite seemingly leaving his employment. He married at St Andrew’s Church, Westland Row, in August 1938, with his address given as ‘Farney’, Mount Merrion. By then he was employed as a ward master in the South Dublin Union hospital, a public institution and former workhouse that catered for Dublin’s poorest.

The onset of the Second World War saw O’Duffy engage cautiously with Dublin’s pro-Nazi underworld. In November 1941, the German spy Hermann Görtz (known to have held meetings with O’Duffy) was captured by the Gardaí and imprisoned initially at Arbour Hill. In notes from jail, he pondered how best to escape. In one such note he mentioned ‘one possible communication route which I have not yet used … a man who was at one time General O’Duffy’s driver and who is a corporal here’. The name of this guard was not given, and it is unclear to whom Görtz was referring. Görtz may simply have been mistaken or confused in his information. A corporal, Joseph Lynch, was known to have smuggled messages for Görtz, but he is not known to have had any associations with O’Duffy. The cryptic reference remains ambiguous. Details of Butler’s life during the Emergency are unknown, except that he planned to emigrate to England after the war to join his wife.

Görtz concluded by mentioning that he had received a ‘mysterious note’, which indicated ‘that the general may be willing to help me’. But his schemes came to nothing and he remained under lock and key. Fearing deportation to Germany after the war, he committed suicide in 1947.

O’Duffy was apparently disappointed in Butler for planning to emigrate to England. On a return trip to Ireland shortly after O’Duffy’s death in November 1944, Customs in Dublin told Robert ‘Your boss is dead’, to which he replied ‘I’ve only just left him’, referring to his employer in England. ‘Not that boss’ was the response from the Customs officer, indicating that Butler’s connections to the late General O’Duffy were common knowledge.

In England Robert Butler lived a content and ordinary life as a motor mechanic, becoming a father and grandfather. On a return trip to his home town in August 1990, the local newspaper reported that the 84-year-old former chauffeur to O’Duffy, then living in Northampton, was ‘home on holidays’, as it detailed his history as a driver for O’Duffy, ‘who played a prominent role in the national life in Ireland in the 1930s’, and how he ‘also served in the Irish contingent with General Franco’s Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War’.

Relatives of Butler recall that in his post-war life in England he was a firmly patriotic Irishman but lived a largely apolitical existence. Slight allusions to his past life included a habit developed in his old age of using the Spanish word sí to answer in the affirmative. Butler died in 1997 and his ashes were interred in the family burial plot at the Rock of Cashel.

Above: Thomas Jolly in his role as chauffeur to Dr Eduard Hempel, head of the German legation in Ireland. (Stephen Jolly)

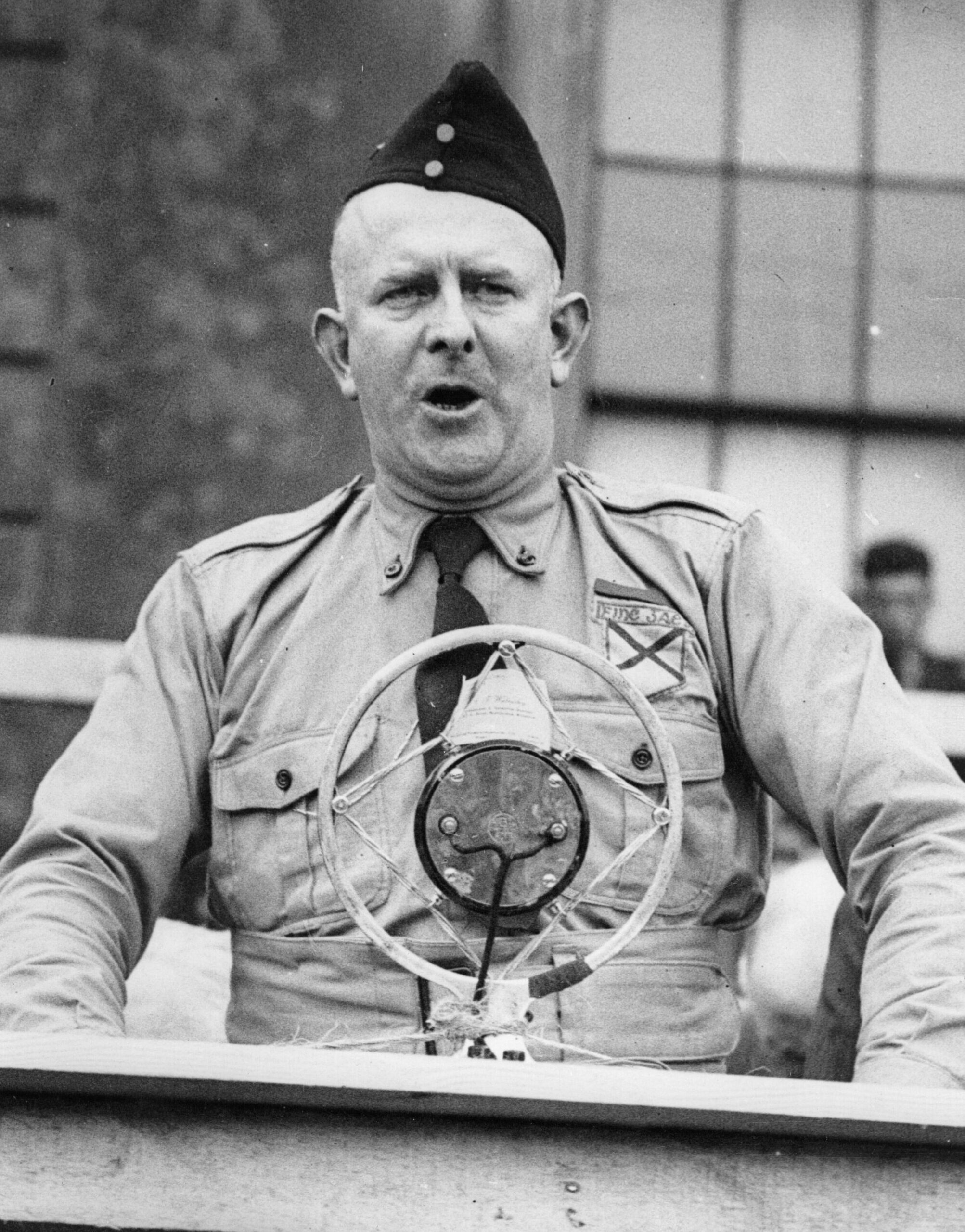

Above: General Eoin O’Duffy addressing a Blueshirt meeting in 1934. Although by then his career was already in decline, his two drivers remained loyally in his service.

THOMAS JOLLY

The other individual to work as O’Duffy’s driver was County Monaghan native Thomas Jolly, born in 1912 out of wedlock to a Protestant middle-class doctor from Clones and his maid. His upbringing was neglectful. Jolly never received an education and remained illiterate for the rest of his life. As a young man he moved to Dublin in search of work. By 1934 he had fallen in with the Blueshirts. Employed as a driver for O’Duffy, Jolly also moved into ‘Farney’, where he likely performed household tasks in addition to chauffeuring duties. Physically tall and strong, Jolly was well suited to a role that included physically protecting his controversial boss.

In November 1936 he followed his leader to Spain. He and other Irishmen acted as military guards at a prisoner-of-war camp, where he saw the abject cruelty and brutality of the Spanish conflict. In later life, Jolly recollected a disturbing incident in which Russian prisoners (Republicans) were shot bullet by bullet, beginning in the foot and gradually moving upwards. They allegedly cried out ‘Stalin! Stalin!’ in an act of defiance. Jolly’s grandson credits this incident with shifting Thomas Jolly’s thinking: he could not help but be impressed by the resistance shown by those Soviet prisoners in their last moments of life.

In June 1937 the Irish brigade returned home from their inglorious involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Personality clashes, allegations of corruption and poor conditions had marred their experience. There was no triumphant return to Ireland for O’Duffy. His political career was over. He spent his final years in relative obscurity, trying to salvage the reputation of his brigade before eventually undertaking a second stint as president of the apolitical National Athletics and Cycling Association. Jolly remained on O’Duffy’s payroll, although Butler had left his service by 1938. Liam D. Walsh, O’Duffy’s secretary, wrote in 1945 that the late general ‘had the utmost trust and confidence in [Jolly]’ but regrettably had to let him go owing to economic restrictions imposed by the Emergency.

During the Second World War, O’Duffy publicly supported a policy of neutrality whilst remaining on close terms with the Axis ambassadors in Ireland. In November 1943 he secured a job for Jolly as chauffeur to the head of the German legation in Ireland, Dr Eduard Hempel. Jolly moved into the German diplomat’s official residence, the opulent Gortleitragh house in Monkstown, where he also worked as a gardener. During this time Jolly married and fathered his first child. Shortly after his daughter’s birth, he arrived at the Rotunda maternity hospital sporting his swastika-laden uniform, which caused consternation among the other mothers on the ward.

When O’Duffy died in November 1944, he left £100 and his car to Jolly in his will. Notably, Butler was not included in O’Duffy’s will (revised in September 1943), perhaps owing to their disagreement over Butler’s plans to emigrate.

The defeat of the Third Reich in 1945 had a crushing effect on Jolly’s life. Hempel, who resigned his diplomatic post, continued living in Gortleitragh until 1950 with his family, but their servants and domestic staff were let go in 1945. Although Jolly successfully secured employment as chauffeur to the state pathologist, he later lost this job and from the 1950s onwards worked as a labourer and lived in Sallynoggin.

The rest of Jolly’s life was largely apolitical. His social profile as a working-class labourer gave no indication of his earlier life as a fascist volunteer in Spain or as a driver successively for Ireland’s most prominent fascist politician and the Nazi ambassador. His grandson, Stephen Jolly, recalled that Thomas did not harbour the intense hatred of communism that typifies many fascists. He was deeply cynical about religion and espoused anti-clerical views. On South Africa, Jolly felt a natural aversion to the racist policies of the apartheid regime and strongly supported Muhammad Ali. Like Butler, Jolly’s post-O’Duffy life bore no traces of a fascist pedigree.

Both Butler and Jolly worked closely with O’Duffy, even after his political downfall. Their experience of the Spanish Civil War seemed to leave no great lasting impact on either man. Perhaps this assessment could also be applied to the Blueshirt movement itself, which at one point appeared to be a significant force that might overturn Irish democracy but ultimately ended up being a flash in the pan.

Jack Traynor is an Irish Research Council-funded Ph.D candidate at the Department of History in Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

- McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy: a self-made hero (Oxford, 2005).

- Manning, The Blueshirts (Dublin, 1970).

- Traynor, General Eoin O’Duffy: the political life of an Irish firebrand (Jefferson, NC, 2024).