By Donnacha Ó Beacháin

For centuries neither Ireland nor Ukraine was on the world map but rather they were provinces or sub-units within the imperial structures that had conquered their peoples militarily. Britain and Russia feared that Ireland and Ukraine respectively would be used as a base for foreign attack, and this provided one of the motivations for invasion and occupation. The British and Russian political élites denied that Ireland and Ukraine were colonies and this frequently provoked contradictory sentiments. Geographically close to their respective invaders, the Irish and Ukrainians were politically alien. They were both kindred and exotic, familiar and yet unknown, warm-hearted—soft, even—but at the same time disloyal and dangerous. England’s or Russia’s difficulty was frequently viewed as an opportunity for the national advancement of Ireland and Ukraine. The formal end of empire did not extinguish imperial modes of thinking. Britain and Russia considered Ireland and Ukraine to be in their respective spheres of interest and neither believed that their former colonies should be treated as equals—or, indeed, as fully sovereign states with divergent interests.

IMPERIAL DIFFICULTIES, NATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES

Arguably, the time when the histories of Ireland and Ukraine most closely aligned was between 1914 and 1921, when the tumult of the First World War collapsed empires and facilitated the birth of new states. On 18 September 1915, the front page of Nationality, the newspaper edited by Arthur Griffith, argued that ‘If England in Ireland has learned much from her Russian ally, Russia on her part has been taught true Imperial lessons by her British exemplar’. The paper noted that British imperial governance in Ireland was more refined than Russian rule in Ukraine for the simple reason that the former had greater experience over a longer period. Nationality emphasised that during its recent and short-lived occupation of Austrian Ukraine (eastern Galicia) Russia had used ‘religious and political persecution, prescription of language and press, destruction of schools, libraries, and museums, and the whole paraphernalia common to all conquests in Ireland’.

With the overthrow of the Tsarist regime in Russia, Ukraine’s strides towards independence attracted interest and admiration in Ireland. On 16 February 1918, Nationality noted that ‘the Ukrainians have been described by an English writer as “the Irishmen of Russia”’—their virtues being depicted as intelligence, courtesy, love of learning, great bravery and patriotism, but lacking in the ‘practical qualities’ of the ‘Great Russians’, before concluding that ‘they have shown that they possess an eminently practical sense in connection with playing and winning their hand in this war’. Sinn Féin argued that, following independence, Ukraine could enjoy a cultural renaissance, a prospect to which Ireland might also look forward once it exited the British Empire. Nationality noted with satisfaction that whereas fourteen years earlier the Ukrainian language had been illegal it was now the language of international treaties with Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey.

UKRAINE’S VICTORY IS IRELAND’S VICTORY TOO

As the First World War subsided, both Ireland and Ukraine intensified their struggles for self-determination. Never had the fates of these two nations been so much in harmony. In an editorial published in 1918 entitled ‘The Day of “Small” Nations’, Nationality rejoiced in the reduction of Russia, which would no longer ‘lie like an abominable wet blanket over the national aspirations of small nations whose very name and whose very existence it carefully hid from the world’. Ukraine’s success, the Sinn Féin periodical argued, was a victory for other emerging nations like Ireland, and Russia’s diminution a blow against imperial domination.

Young Ireland, a republican newspaper targeting Ireland’s patriotic youth, observed how Muscovites referred to Ukrainians as ‘Little Russians’ and that they were considered ‘the “West Britons” of the Russian Empire’. The paper noted how all travellers of repute during the previous two centuries had impressed on their readers the impossibility of believing in national unity between Russians and Ukrainians. ‘They were by nature different in temperament, history, tradition, character and language,’ the paper emphasised. ‘They were, and are, as different as the Irish are from the English.’

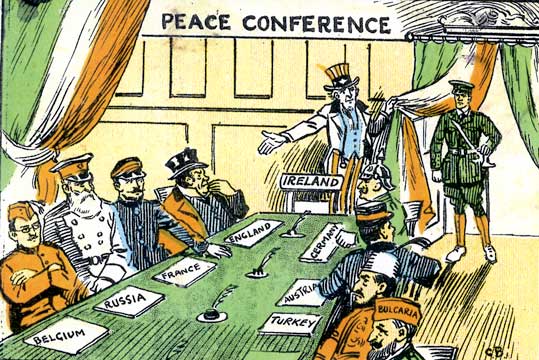

Sinn Féin was eager to emphasise the republican character of the new Ukrainian state, given that the party sought recognition for an independent Irish republic and would contest a general election later that year against rival nationalists who advocated a modest form of Home Rule within the British Empire. By achieving a republic, Ukraine had ‘proved its national claim’, maintained Nationality, before its editorial asked rhetorically: ‘are we ready to face the peace conference [at Versailles]?’

Irish and Ukrainian socialists corresponded. In a piece entitled ‘Celts of Russia keen on Ireland’, The Watchword of Labour published communications from the Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionary Party, which informed them that articles related to Ireland’s fight for freedom appeared in the party’s main publication, Borotba (‘The Struggle’), and that ‘the Ukrainians are very much in the same plight as you in Ireland’. The editor of The Voice of Labour, Cathal O’Shannon, authored several articles in Irish and English about Ukraine. ‘I understand what unites and differentiates Ukrainians and the Irish’, O’Shannon wrote to his counterparts in Ukraine and, on behalf of the Labour Party and the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, he expressed ‘heartfelt and sincere gratitude … for your interest in our cause’. In February 1919 O’Shannon and Thomas Johnson were admitted as Irish representatives to the International Labour and Socialist Conference—the first gathering of European labour and socialist parties since the outbreak of the First World War. Both men were elected to the body’s Permanent Commission, which in April 1919 adopted a resolution supporting Ukrainian self-determination.

IRELAND AND RUSSIAN IMPERIALISM

Not every radical publication in Ireland during the revolutionary upheaval extolled the virtues of an independent Ukraine. The New Ireland newspaper, edited by future Fianna Fáil TD Patrick Little, had a romanticised view of how Bolshevik Russia approached the smaller states that had until recently formed part of the Russian empire. This is not altogether surprising, given the character of Tsarist rule and the reforming rhetoric of the communists who had dislodged the Romanov dynasty.

As president of the Irish Republic, Éamon de Valera authorised negotiations with the Bolsheviks to see whether mutual recognition could be achieved. A draft treaty between the new Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and the Irish Republic was drawn up in early 1920, and the Irish loaned $20,000 (more than a quarter of a million dollars in today’s money) to the Bolsheviks in return for some of the tsar’s jewels as collateral. However, when an Anglo-Russian trade agreement, which included a commitment to end Soviet propaganda against Britain, was signed on 16 March, enthusiasm amongst the Bolshevik élite for enhanced relations with republican Ireland waned. As a result, the Irish–Russian treaty was never ratified.

A report compiled in 1921 by Sinn Féin’s plenipotentiary in Moscow, Patrick McCartan, showed that by this stage he had few illusions about the Bolsheviks whom he encountered. ‘Nobody in authority in Russia pretends to think that such a thing as liberty exists,’ he wrote, and while the government claimed to be a dictatorship of the proletariat it was ‘nothing of the kind’, but rather ‘a dictatorship of about half a dozen leaders of the Communist party’. The Sinn Féin leader noted that, for all the talk of internationalism in Russia, there was ‘not only nationalism but imperialism’, and he cited attitudes towards the Baltic States:

‘The Russian laughs at the Estonian language as the British are accustomed to laugh at the Irish language. It is vulgar, horrible etc. I am not so sure therefore that self-determination for Ireland would raise much enthusiasm in official circles.’

McCartan concluded that ‘it is impossible to do any propaganda for Ireland in Russia’. This was because, to his mind, propaganda targeted people so that they might in turn influence their government, whereas ‘the people of Russia do not count and hence it makes no difference what they think. The present Government is not responsive to them.’ McCartan conceded that he would not have reached such conclusions had he not travelled to Russia, and he believed that others would maintain an unjustified optimism for want of making a similar journey.

INDEPENDENCE?

With the establishment and expansion of the USSR, Ukraine again disappeared from the view of most people in Ireland and, indeed, the world. When it rejoined the ranks of independent states in 1991, new opportunities for interaction with Ireland emerged. On 25 December 1991, the flag at the Soviet Embassy on Orwell Road in the Dublin suburb of Rathgar changed from the hammer and sickle to the white, blue and red of the Russian Federation. Six days later, Ireland formally recognised Ukraine and on 1 April 1992 bilateral diplomatic relations were established.

Garret FitzGerald sounded some words of caution. The former taoiseach had been the first Irish foreign minister to visit the Soviet Union and he appreciated how ‘losing’ Ukraine would be received in Russia. In an article published in May 1992 that drew explicit parallels with Ireland’s efforts to leave the United Kingdom, FitzGerald wrote that ‘many in Britain have never been able fully to understand how we could have wanted to leave what they saw as an Anglo-Irish partnership in the United Kingdom. The Russians feel the same today about their breakaway republics.’ Where did empire truly end and independence begin? For Ukraine and Ireland, William Faulkner’s observation holds true: ‘The past is never dead, it’s not even past’.

Donnacha Ó Beacháin is Professor of Politics at Dublin City University.

Further reading

O. Kushnir, Ukraine and Russian neo-imperialism (Lanham, 2018).

T. Kuzio, Ukraine: democratization, corruption, and the new Russian imperialism (Santa Barbara, 2015).

S. Velychenko, State building in revolutionary Ukraine (Toronto, 2011).