By Paul Dixon

On 12 April 1975, the general officer commanding (GOC) Northern Ireland (1973–5), General Sir Frank King, launched a remarkable public attack on the Labour government’s Northern Ireland policy. The government’s ceasefire with the IRA (1974–5) and determination to end internment had, effectively, stabbed the Army in the back. The ceasefire could hardly have come at a worse time, because ‘in another two or three months we would have brought the IRA to the point where they would have had enough’. Now the IRA were regrouping, and with the release of the hard core of internees by October 1975 ‘they will be able to start all over again’.

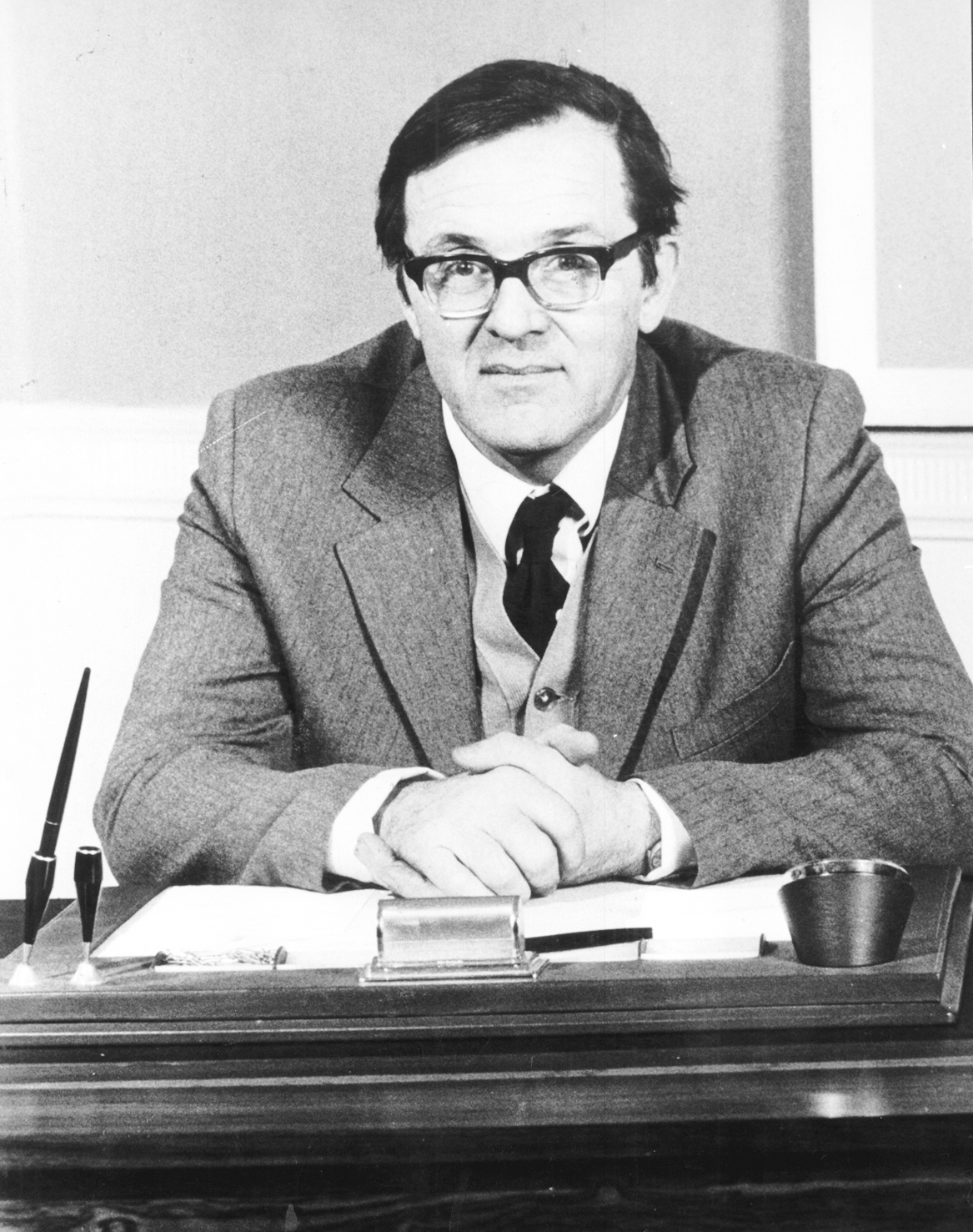

Labour’s secretary of state for Northern Ireland (1974–6), Merlyn Rees, publicly accepted King’s apology and excuse that the attack had been a ‘mistake’ and that he had not expected there to be journalists present during his speech. Privately, ‘government sources’ reported that he was ‘highly perturbed to say the least’. General King’s public outburst did reflect his and the Army’s privately expressed frustration with Labour’s Irish policy. Just three weeks after the GOC’s speech, at a meeting in Stormont on 2 May 1975, General King told Rees:

‘… that the Army’s assessment of the current security situation led to significantly different conclusions from those described by the Secretary of State. HQNI [Headquarters Northern Ireland] and all battalion commanders were becoming increasingly worried by the developments which they saw on the ground, by the current level of violence and by the Government’s overall policy, which appeared to be striving to facilitate the achievement of the PIRA’s aims.’

Confidence that the IRA were about to be defeated was not reflected in private briefings to the secretary of state. In his private diary, Rees claimed that King ‘would not uphold in any analysis’ the claim that the Army were beating the IRA. In his memoirs he stated: ‘Never was I advised, even remotely, that the paramilitaries of any hue could be defeated’.

During 1971–6, the Army’s constant optimistic claims and assertions of impending victory—regardless of the realities—placed maximum pressure on Conservative and Labour governments to acquiesce in the Army’s more repressive approach to the conflict.

THE HIDDEN POWER OF THE ARMY IN THE BRITISH STATE

General King’s attack on the Labour government reflected the rarely acknowledged crisis within the British state over Northern Ireland during the period 1971–6. Republicans have tended to portray British policy as if it were conducted by a single rational actor with a strong determination to retain the Union. Although some acknowledge the more complex reality of policy-making, including the existence of ‘securocrats’ within the state, the monolithic view of the state, like the popular Westminster model, suggests that power and responsibility lie in the hands of the politicians. Collusion and the landmarks of repression such as ‘the Falls Road Curfew’ (July 1970), internment (August 1971) and ‘Bloody Sunday’ (January 1972) are therefore laid at the door of the politicians.

Authoritarians, who are often close to the British Army, also tend to see the British state as a single rational actor, but they tend to attribute any apparent success to the influence of the Army and deflect responsibility for failure onto the politicians. For example, they claim that it was the Army that was responsible for ‘Operation Motorman’, which cleared the ‘no go’ areas of Derry/Londonderry in July 1972. Political–military tensions, which expose the power of the Army and its threat to British democracy, are either ignored or played down.

Huw Bennett’s Uncivil war: the British Army and the Troubles, 1966–75 (2023), like other military histories, portrays the Army in a positive light. The Army ‘acted to save Great Britain from disaster’. By 1975 ‘military strategists’ considered the conflict ‘unresolvable’ (contradicting General King’s and the Army’s claims that they were on the verge of victory). The Army had a ‘distaste for politics’, preferring to concentrate on tactics and ‘avoid the messy political world’. Bennett generally attributes responsibility for repression to ‘the politicians’ rather than the military. Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath (1970–4) made a bid for ‘military victory’ from February to November 1971. Other military historians have portrayed the Army as the ‘victim’ of the politicians and British civil–military relations as the model for emerging democratic states. Since 9/11, however, the military’s power to manipulate government strategy has become more obvious.

THE BRITISH STATE CRISIS PERSPECTIVE

In the retreat from Empire the Army had considerable—in some cases dictatorial—power to fight insurgencies, and so they resented the political ‘interference’ and constraints placed on their behaviour when operating in the UK. Conservative and Labour governments had some influence but not control over the Army in Northern Ireland, and much less control over the RUC and UDR. Successive GOCs opposed government policy and resisted it through both democratic and undemocratic means, including deception and manipulation.

The ‘British state crisis’ perspective emphasises the importance of the severe tensions within the state for understanding policy. Generally, the leaders of the Conservative and Labour parties pursued a broadly bipartisan and conciliatory policy, even if this was not the outcome (indeed, some politicians supported particular repressive measures). First, there was an attempt to reform Stormont to accommodate nationalists (1969–72). When this failed, the first peace process (1972–4) attempted to construct a power-sharing experiment (1974).

Authoritarians rejected conciliatory bipartisan policy as ‘appeasement’, and even treachery, because attempting to pacify nationalists encouraged the IRA to escalate their war in the belief that they were winning. These authoritarians were to be found on the Powellite/Thatcherite or hard right of the Conservative Party but also included powerful elements in the Army (particularly within Northern Ireland), MI5, the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Unionism.

After the introduction of direct rule in March 1972 there was intense conflict between the Conservative government and the Army. The new Conservative secretary of state for Northern Ireland, Willie Whitelaw (1972–3), adopted a more conciliatory ‘softly, softly’ approach to security in order to encourage a peace process that might end the conflict. A lower profile was imposed on the Army and ‘special category status’ for paramilitary prisoners was introduced to facilitate secret talks with the IRA in July 1972.

Authoritarians were furious. GOC General Harry Tuzo (1971–3) claimed that he could ‘break the will of the IRA’ within thirteen weeks and delivered a blistering critique of the Conservative government’s conciliatory peace process strategy. According to Tuzo, the troops were ‘sitting targets’ without the ‘will’ of the government ‘to retaliate against the known enemy’. He opposed the release of the internees and wanted greater powers of arrest for the Army: ‘[T]he time had come to cease acting in a civilised way against an uncivilised enemy’.

Conservative MP Enoch Powell had considerable public support and influence, not least on Margaret Thatcher (Conservative Party leader 1975–9, prime minister 1979–90). On 28 July 1972, following revelations of the government’s talks with the IRA and ‘Bloody Friday’ (when IRA bombs killed nine and injured 130), Powell delivered a public attack on the government’s Irish policy, arguing that its failure to defend the Union cost lives.

BRITAIN’S PALESTINE SYNDROME AND THE ARMY’S EMERGENCY

Britain’s hold on Northern Ireland was precarious. In Palestine (1947–8), casualties inflicted on British troops had led to the rise of an irresistible withdrawal campaign. The ‘Palestine syndrome’ influenced British policy-makers during the retreat from Empire and the determination of the party leaders to establish a bipartisan approach to Northern Ireland. Party conflict at Westminster, with Labour aligned with the nationalists and Conservatives with unionists, could escalate the conflict and stimulate public demands for a pull-out, with the Irish left to cut each other’s throats.

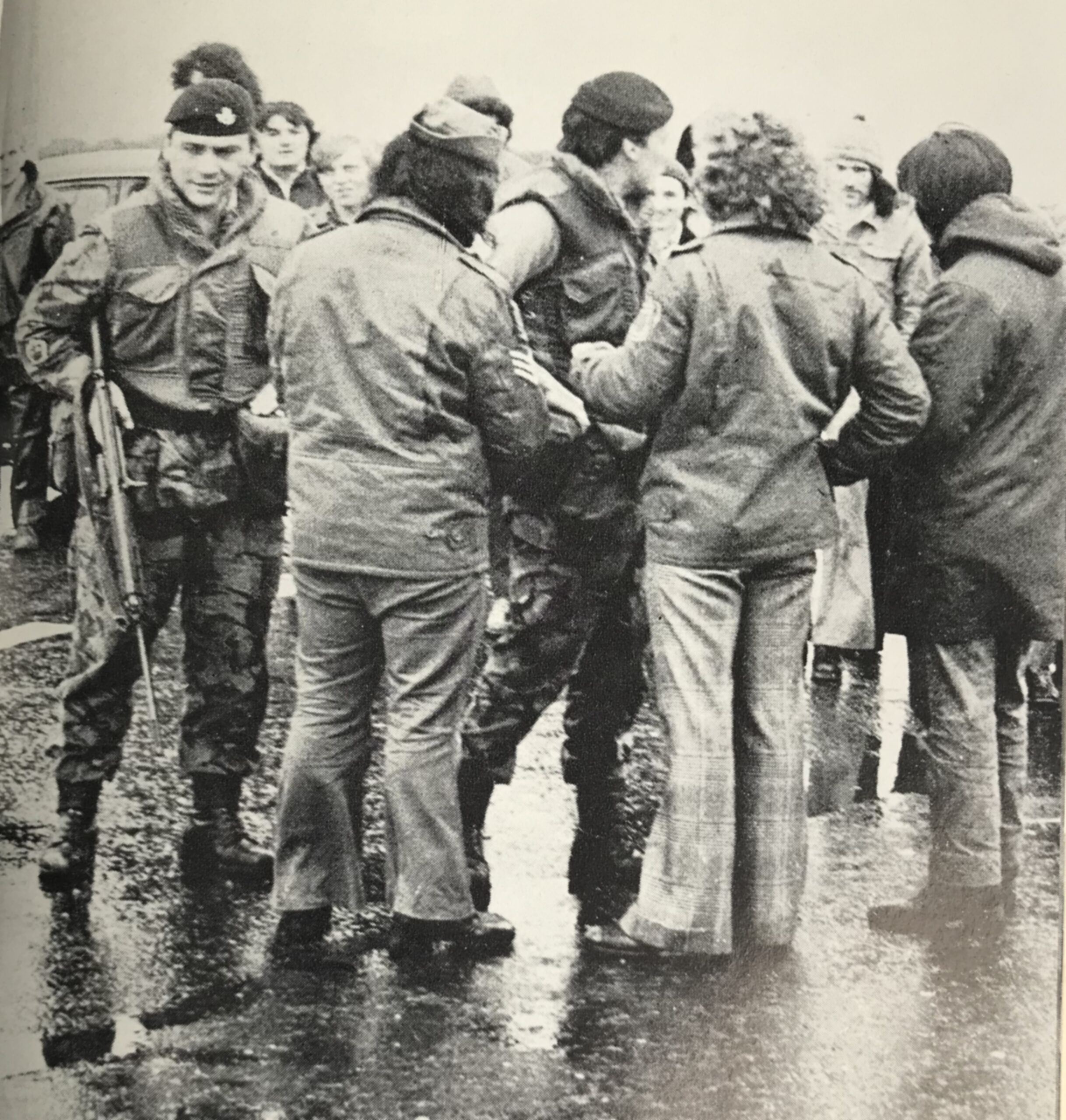

Tensions between the politicians and the Army were exacerbated by the Army’s emergency of recruitment, retention and morale over Northern Ireland. Operation Motorman (31 July 1972) led to the deployment of 22,000 troops in Northern Ireland. By September the head of the Army was reporting that there were problems of recruitment and morale. Between 1972–3 and 1973–4 Army recruitment nearly halved. In May 1973, parents of a serving soldier launched the ‘Bring Back the Boys from Ulster Campaign’, which raised 42,535 signatures in just over a month. Future prime minister James Callaghan told parliament that ‘Britain cannot bleed forever …’. There were concerns that the Army might break over Northern Ireland, which led to an urgency to ‘Ulsterise’ the conflict.

SECURITY BIAS AND ULSTERISATION

The Army’s emergency led to an urgency to withdraw British troops and replace them with locally recruited security forces. By this point, nationalists had become alienated from the security forces, so their participation was low. Generally, Ulsterisation represented the arming of unionists to police nationalists. This was problematic because, as the Army acknowledged, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the locally recruited regiment of the British Army, the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), had only a conditional loyalty. Furthermore, there were difficulties in recruiting sufficient numbers of unionists into the RUC and UDR.

There was a systemic bias in security policy against nationalists. The Army wanted to avoid an unsustainable war on two fronts against both republican and loyalist paramilitaries, so they took on republican paramilitaries, arguing that this would remove the motivation for loyalist paramilitaries to mobilise. Pragmatists within the Army did not believe that the IRA could be defeated and argued that security operations needed to be moderated to encourage nationalists into a political accommodation. Militarists, such as GOCs Tuzo and King, were pro-unionist, claiming that the IRA could be militarily defeated and consequently there was no need to conciliate nationalists. General King stated ‘that at all costs we must remain friends with the Protestants’. He was also critical of the peace process and reluctant to use the Army against the Ulster Workers’ Council strike (1974) to save power-sharing.

THE ARMY’S LOYALTY?

The Labour Party leadership were concerned about the loyalty of the British Army. There was a fear that the Algerian war (1954–62) had led the French Army to mutiny and that the British Army might respond similarly to the retreat from Empire. Labour’s defence secretary (1964–70), Denis Healey, recalled that after the Labour government threatened to act against the white regime in Rhodesia there were ‘mutinous mutterings’ from the Army.

During the 1970s, Labour leader Harold Wilson and his close advisers discussed withdrawal from Northern Ireland under the codename ‘Algeria’. In April 1974, Prime Minister Wilson met GOC General King. Bernard Donoughue, a close Wilson adviser, recorded in his diary that the Army were ‘very angry with the restraints put on them. Wanted mandatory justice. A sign of what a cancer Ireland is. Britain’s Algeria, brutalising the whole community.’ On the Labour Left there was more concern over the precedent of Chile, where the military had also been involved in a coup, along with the CIA, against the socialist President Allende.

The battle between political conciliators and militarist repressors in Northern Ireland had severe consequences for policy. Conservative and Labour governments experienced strong resistance from the Army, RUC and UDR. By October 1974 Merlyn Rees, secretary of state for Northern Ireland for just eight months, still believed that he could rely on the Army. Yet by then the Army was already resisting government policy, including by the use of ‘dirty tricks.’

The Army had opposed taking action to save power-sharing in May 1974 and had briefed the media against the government. In July 1974 the Army supplied false information on the reinvolvement of released detainees in violence in order to manipulate government policy against further releases. Consequently, in August 1974 a ‘Northern Ireland Information Policy Co-ordinating Committee’ was formed to bring the Army’s information policy activities under political control. In March 1975 it was reported that the government had closed down a ‘black propaganda’ campaign by Army officers.

UNDERMINING THE LABOUR GOVERNMENT

During the IRA’s 1974–5 ceasefire, the Army and the RUC undermined government policy and the ceasefire by provoking republicans and interfering with talks. General King’s public and private attacks on the Labour government in spring 1975 were the manifestation of the authoritarians’ resentment towards the conciliators.

The British state’s crisis over Northern Ireland is the context in which some on the hard right attempted to undermine Labour and Conservative governments, who consequently were unable to fully control their security forces. By 1987, revelations from Army whistle-blowers Colin Wallace and Fred Holroyd had convinced Merlyn Rees that while he was secretary of state ‘there were efforts to seriously discredit political figures both in Britain and Ireland and in effect to establish a right-wing Government in Britain which would hammer terrorism be it IRA or loyalist’.

Professor Paul Dixon teaches at the Universities of Leicester and Queen Mary University of London and is the author of The militarisation of British democracy (forthcoming).

Further reading

H. Bennett, Uncivil war: the British Army and the Troubles, 1966–75 (Cambridge, 2023).

P. Dixon, ‘“Striving to facilitate the achievement of the PIRA’s aims”? The Labour government, the Army and the crisis of the British state over Northern Ireland 1972–76’, History 109 (386–7) (2024), 367–94.