Alvin Jackson

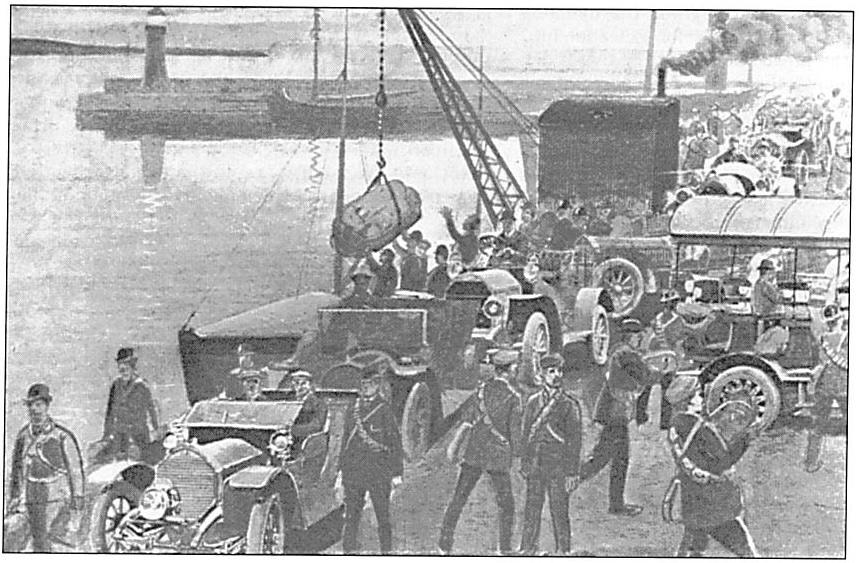

One central episode in the Unionist campaign of 1912-14 may be used to illustrate the strategic dilemma faced by the leaders of the movement and the success with which setbacks and complexities were concealed. On the night of 24-25 April 1914, militant Unionists, led by the quixotic Major Fred Crawford, landed 25,000 rifles and three million rounds of ammunition, principally at Larne in County Antrim. These weapons were swiftly distributed and effectively concealed: some caches were in fact so well hidden that they have only come to light in the routine searches for weapons conducted by the British Army since 1969. The loyalist gunrunners had apparently achieved both an unequivocal military as well as political victory. They had achieved a crude amplification of the UVF’s fire-power as well as a grim corroboration for their rhetorical challenge to Home Rule. The event was thoroughly publicised, with celebratory demonstrations, the compilation of a souvenir booklet, and with extensive coverage in the British and European press. The gun running was chronicled by a leading Ulster Unionist, Ronald McNeill, in the illuminating, if partisan, Ulster, I Stand for Union (1922). Fred Crawford and more minor conspirators subsequently committed their individual testimonies to print.

LARNE AND THE ANGLO-IRISH AGREEMENT

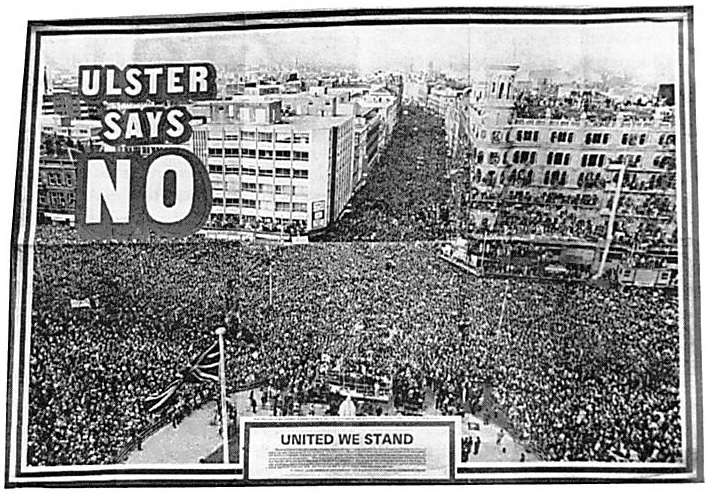

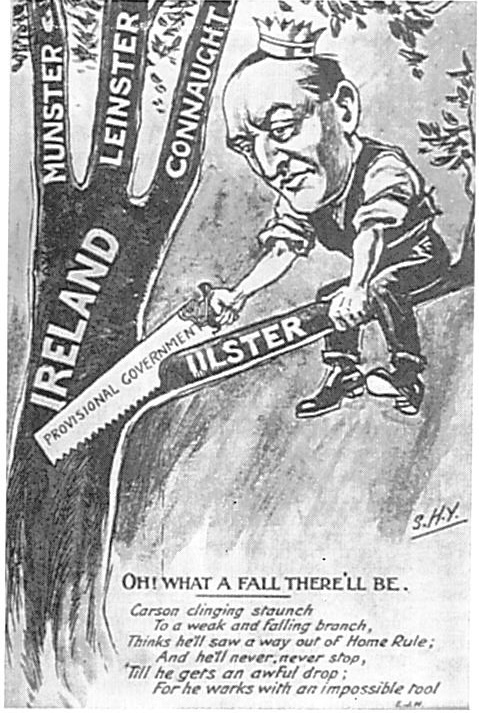

The centrality of this episode for the historical perceptions of contemporary Unionism may be gauged by the attitudes of a leader like Ian Paisley as well as by the number of popular accounts at present available. Invocations of Crawford and the gunrunners by Dr Paisley and others occurred extensively after the 50th anniversary of Larne (in 1964), but they undoubtedly reached a peak of intensity in 1986-7, in the months following the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Larne, and the events of 1912-14 in general, have for long had a symbolic significance within loyalism, and their relevance was apparently underlined in the aftermath of the Hillsborough Accord. Unionist militancy at the time of the third Home Rule Bill, building to a crescendo at Larne, was a measure of the distance between loyalism and mainstream British politics, and it reflected mutual distrust and incomprehension – even between loyalism and British Conservatism. Equally, the Anglo-Irish Agreement confirmed the distance between the British parties and contemporary loyalism, with the Unionist political and social command being treated to a near-comprehensive English Tory disdain. The suspicion that an English governing class regarded loyalism as a colonial subculture evolved into a certainty in November 1985.

‘SNIVELLING WRECKS OF MANHOOD’

Thus, the political isolation of 1914 became the isolation of 1985, and the political expedients of 1914 became the suggested strategies of 1985. Just as in the era of Terence O’Neill, so in the aftermath of Hillsborough the Unionist establishment as well as populist loyalism turned to Carson and Crawford for validation. Paisley and O’Neill had vied for the legacy of Edward Carson in the 1960s, while since 1985 radical loyalists in the UDA and elsewhere have sustained this populist challenge, though increasingly against an Unionist establishment whose chief ornament is now Dr Paisley himself. In the months following Hillsborough, the ideologues of the UDA recalled Fred Crawford and the Unionist commanders of 1914 in highlighting the perceived inadequacy of the party leaders in the 1980s: ‘students of history’, noted a UDA commentator in February 1987, ‘will contrast and compare the snivelling wrecks of manhood who masquerade as political leaders in the 1980s with the giants of Ulster’.

Unionists of different hues have sought to jog memories of April 1914, even through the re-enactment (in 1989) of the events at Larne: the Larne pageant may yet join the Closing of the Gates at Derry and the Sham Fight of Scarva in the Mystery Cycle of loyalism’s evolution. The iconography of 1914 has been revived in other ways: a postcard of an armed and defiant young woman (‘Ulster 1914: ‘Deserted! Well I can stand alone’‘) has been deployed with a particular and grim enthusiasm. The first wall painting depicting an image from 1912-14 appeared in 1987, part of a revival of loyalist mural art originating in 1984-5. Yet, setting aside the imagery and hyperbole current in Orange pubs and clubs, it is arguable that, as with the contemporaneous gun-running at Howth, the usefulness of Larne lay as much in the publicity which was generated, as in any more tangible legacy. The gun running reflected a much more complicated debate inside Unionism than the publicists of 1914 were willing to recognise, or their audience – which includes contemporary Unionism – has sought to elucidate.

It would be utterly misleading to undervalue the commitment of the loyalists in 1914, and pointless to bewail the role that their actions play, and have played, in the historical perceptions of loyalism. Judged as a response to British government policy, judged in terms of the personal devotion involved, or in terms of logistics, the gun running was a spectacular tactical success; its subsequent celebration in loyalist popular culture (song, ballads, community history) is not difficult to understand.

RHETORIC AND REALITY

Yet it is also possible to offer other, in certain respects more complicated, perspectives on Larne and its significance. Judging the distance between the popular celebrations of loyalist achievement and the surviving evidence of their activity is one measure of the success of Unionist publicity. It is also, arguably, a measure of popular self-delusion. Given the role of 1912-14 in loyalist folklore, both before, but especially after 1985 (the actions of leading politicians, the form of demonstrations, celebratory publications), it is possible that Unionists are being swayed by a particular rendering of their own past. A Whiggish reading of 1912-14, and of its consequences, shapes both historical perceptions, and also the Unionist response to contemporary demands. As with aspects of contemporary Nationalism, a simplified version of the past helps to validate simplified responses to contemporary demands.

The historian Patrick Buckland, some twenty years ago, rightly distinguished the bellicosity of the UVF from the convictions and priorities of the Unionist political leadership: ‘most of the political leaders of Unionism hoped and thought that the UVF would not have to fight’. Archival evidence made available since this comment was published (in 1973) has confirmed the hesitancy of the Unionist leadership, the distance between their qualms and their rhetoric. The UVF was useful as a means of channelling loyalist emotion away from the kind of street confrontation which had been so damaging, both politically and financially, in 1886. But the usefulness of the UVF depended on the strength of its morale, and this in turn depended on its being gainfully employed. In these contingencies lay a very profound political dilemma for Unionism in 1913-14.

On the night of 24-25 April 1914,militant Unionists landed 25,000 rifles and three million rounds of ammunition,principally at Larne in County Antrim.

‘MASTERLY INACTIVITY’

The Liberal government’s inertia over Ulster – the Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith’s ‘masterly inactivity’ – had perhaps a more solid rationale than some commentators have allowed. It was a strategy based, not upon ignorance or carelessness, but upon intelligence reports of the condition of Ulster Unionism. Simply by doing nothing, Asquith could permit the Unionist leadership to become prisoners of their own logic, penned in by their own indecision over violence, and by their own supporters’ desire for a more assertive command. Aggression, by any realistic assessment, threatened sympathy in England; inertia threatened morale in Ireland, as was increasingly clear within the UVF by late 1913. In so far as the Unionist leaders showed themselves willing to negotiate with Liberals and Home Rulers, even in the potentially most compromising of venues, in so far as they radically scaled down their demands between 1911-12 and 1914, then Asquith’s ‘strategy’ of delay was rather more than an euphemism for indifference or idleness.

THE UNIONIST IMPASSE; HAWKS AND DOVES

Viewed in this light, the Larne episode emerges as one further stage in the process by which Unionists backed themselves into an impasse. Some influential Unionist leaders grasped that the interests of the movement lay in threat rather than in action, and were accordingly unhappy about the importation of arms, and certainly unhappy about their distribution. Police reports of Unionist gatherings in 1913 and early 1914 suggest that the hard-liners were decidedly in the minority. Before 1914, extremists like Fred Crawford had been fed relatively small amounts of money by the Ulster Unionist Council, and thereby temporarily diverted from any apocalyptic project into small-scale operations. Guns had been brought by the Unionists into Ireland from as early as 1910, but such projects had been designed partly to mollify the hawks (a fact occasionally perceived even by Crawford), and partly to alarm the government. The UUC was not yet investing enough money for these projects to be serious efforts towards equipping an army; but they certainly occupied the conspiratorially-minded, and gave both the Royal Irish Constabulary and Sir James Dougherty, the Under Secretary for Ireland, some cause for reflection. Such activities may be perceived as a further means by which the political leadership sought to condition constitutional negotiation.

IN THE TALONS OF THE HAWKS

By early 1914, however, these gestures towards violence were having as little impact as the wholly rhetorical challenge laid down by organised Unionism in 1886 and 1893. Asquith had not responded by substantial concession, and the Unionist political leadership was therefore left in the talons of the hawks within the Ulster Volunteer Force. The preliminary decision to fund a major gun-running expedition was taken only in January 1914, in the context – significantly – of the abortive private negotiations conducted between Carson, Bonar Law, and Asquith. It represented a climb-down by the political leadership of Unionism, and a recognition of the futility of the existing strategy. In this sense, the Larne gun running, dazzling as a tactical coup, also reflected a profound strategic failure for Carson and his political intimates.

Carson’s increasingly apocalyptic rhetoric in the spring of 1914 – reminiscent of Pearse at his most lugubrious – indicated the quandary which he felt Unionism was in. Violence for Carson was certainly an option – the last option – but he perceived violence in icily realistic terms: as honourable, but also as suicidal. After Larne, when the penalties of incitement were inescapable (because enthusiastic Unionists were now armed), Carson softened his tone. It was as if Larne was an end in itself – as if it alone had been sufficient to satisfy the military honour of the Ulster Unionist movement, and the personal honour of its leaders.

The effective value of the gun running, beyond the undoubtedly central issues of morale and publicity, is questionable. It consolidated the fire-power of the UVF, but then – given the Curragh ‘Mutiny’ – such an exercise was largely redundant for the British were no longer in a position to impose a military settlement. Moreover, the UVF did not need Larne to be able to overwhelm the poorly organised and poorly equipped Irish Volunteer movement. Did Larne strengthen the debating position of the Unionist leadership? The presumption must be that it did, though there were certainly few tangible benefits before August 1914. At the same time, the likelihood of a damaging breach of discipline, of some form of violent incident, was considerably greater after April. The discipline of the UVF, surprisingly good, given the history of popular sectarian confrontation in Ulster, was by no means beyond reproach: any local and armed aggression would have had disastrous implications for support in England and within English Toryism. If Larne made the Unionist leadership a more formidable adversary in the eyes of the Liberal government, then it also made a negotiated settlement all the more desirable – and for everyone concerned, pre-eminently the Unionists.

A ‘DIRTY’ WAR?

Nor did the gun running give Unionists the means to fight a war. Strongly swayed by British Army personnel and precedent, the UVF favoured a ‘stand-up fight’ rather than guerrilla tactics. Indeed guerrilla warfare had been damned in the eyes of loyalist tacticians through its association with the Boer campaign of 1899-1902: the involvement of northern Irish regiments of the British Army in this war had been considerable, with loyalist leaders such as James Craig, Fred Crawford and Robert Wallace having enlisted and served. Accepting conventional and confrontational warfare meant acquiring a formidably stocked arsenal as well as a thoroughly trained army. The UVF was capable of impressing susceptible English journalists, but there are good reasons for supposing that its morale was flagging before April 1914, and that its general efficiency was questionable. And the fruits of the Larne gun running, even taken in combination with earlier weapons importation, did not constitute an adequate arsenal. The Larne episode increased UVF firepower, just enough for this firepower to be a political liability, and yet not sufficiently for it to be an unequivocal military asset. The threat of violence had certainly increased, but not the threat of formalised violence. Informal sectarian or political confrontation was now a greater risk, but the ritualised and ‘honourable’ warfare envisioned by the UVF tacticians was still out of the question. Thus the UVF had the capacity to fight a ‘dirty’ war, and yet this certainly would have sacrificed political opinion in England to the point where Asquith could have imposed a settlement with impunity.

AWAY FROM PLAYGROUND BATTLES

25,000 rifles and three million rounds of ammunition were shipped into Larne in April 1914. Several thousand weapons had been smuggled into Ireland between 1910-11 and the spring of 1914: in addition, there was a relatively large number of arms in Ulster, even before 1910 – partly owing to the troubled recent history of the province, and partly because weapons were used extensively by the farming population. On the other hand, many of the weapons in circulation were extremely old, souvenirs from the 1798 Rebellion, or antiques from the age of the flintlock; and the British police had been relatively successful in locating and impounding weapons bound for loyalist militants. From the perspective both of propaganda and of military credibility, the Larne gun running was of disproportionate significance for the UVF. Until Larne, theirs was a toy army, and the effort to shift away from playground battles had been half-hearted and in any case had been publicly thwarted by the British authorities. Larne was effectively publicised, its significance exaggerated, precisely because it stood in the context of sustained failure. But, building on the success of Larne inside Ireland was rather more challenging than persuading the British public of its significance. And it seems clear that neither the political nor the military leadership of loyalism had any firm idea about future action.

THE POLITICS OF SUICIDE

25,000 rifles did not arm a body which claimed a membership of 100,000. Three million rounds of ammunition spread over 25,000 rifles offered little scope for weapons training or for anything other than a momentary confrontation. The rifles were of three different makes, and no scheme of rationalisation was ever drawn up: it is hard to disagree with Charles Townshend’s conclusion that ‘in a full-scale military clash the UVF weaponry would have created a logistical nightmare’. Larne, therefore, turned an unarmed force into a badly armed force. In both its military and political implications, the gun running highlighted the Ulster Unionists’ difficulties without providing solutions. Carson recognised that violence was the politics of suicide – but his ideological successors have been rather more sanguine in interpreting 1914.

Alvin Jackson is a lecturer in modern Irish history at Queen’s University Belfast.

Further reading:

Patrick Buckland, Irish Unionism 2: Ulster Unionism and The Origins of Northern Ireland, 1886-1922 (Dublin 1973).

Alvin Jackson, The Ulster Party: Irish Unionists in the House of Commons, 1884-1911 (Oxford 1989).

Alvin Jackson, ‘Unionist Myths, 1912-85’, Past & Present, No.136 (August 1992).

Charles Townshend, Political Violence in Ireland: Government and Resistance since 1848 (Oxford 1983).