By Dermot McGuinne

By the year 1641 William Bedell, bishop of Kilmore, had completed a translation of the Old Testament into Irish. His intention was to have the work printed, but owing to the absence of a suitable Irish-character typeface he sought to have a new type prepared. Consequently, at his own expense, he sent to Holland to have a set of punches cut and a supply of type cast. This project was interrupted by the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and was abandoned after his death the following year.

ROBERT BOYLE

About the same time, Robert Boyle (aged fourteen) was pursuing his early education at Eton College in England. Later he travelled with his tutor on the Continent, where he further developed his interest in scientific investigation and languages. He was born on 25 January 1627 at Lismore Castle, Co. Waterford, to Richard Boyle (later 1st earl of Cork) and Catherine Fenton, daughter of Sir Geoffrey Fenton, secretary of state for Ireland. Robert’s father exhorted him to develop a proficiency in the Irish language, then the common means of expression amongst the native Irish. His tutor, Robert Carew, tried to inspire him, only to be met with resistance. He reported: ‘Mr Robert sometimes desires it [speaking Irish] and is a little entered in it’. Despite this early reluctance, towards the end of his life Boyle played a significant and direct role in the production of an irish-character printing type that has largely been overlooked.

Throughout his life Boyle devoted himself to an individualised approach to his scientific research, seldom relying on the work of others. He is particularly known for experimentation into the properties of air, and especially for his theory that the volume of a gas varies inversely to the pressure of the gas—referred to as ‘Boyle’s Law’. He is regarded by many scientists as ‘the father of modern chemistry’. He was a founding member of the Royal Society in London, and was later elected president of that prestigious institute.

‘THINGS THAT ARE FIT TO BE DONE IN THE KINGDOM OF IRELAND’

Boyle’s methodical approach to his investigations led him to prepare many lists of matters deserving his attention. Among these he expressed his interest in the discovery of a method of flying; locating longitudes at sea (a matter of huge importance at the time); drugs to assist in the prolongation of life and to alleviate pain and enhance imagination and influence dreams (perhaps leading to his persistent attempts to transform base metals into gold, without great success); and his unsuccessful experiments into hydrostatic perpetual motion.

One such list, however, specifically identified ‘Things that are fit to be done in the Kingdom of Ireland’. It included ‘That the Bible and Common Prayer Book be translated into Irish and printed in the vulgar character’. This departure into the realm of seemingly non-scientific religious affairs is not altogether surprising. As a devout Anglican, he was inclined to see a correlation between his religious beliefs and his scientific investigations. Consequently, when he became aware of the unfinished work left in abeyance by Bedell in 1641, he embraced the project with enthusiasm. He engaged the assistance of Andrew Sall, a former Jesuit and professor of moral theology at the Irish College in Salamanca who had converted to the Anglican church and who was later appointed chaplain to the lord deputy of Ireland. Sall was a keen Irish scholar with some fluency in the language.

NEW FONT OF IRISH TYPE NEEDED

Sall eagerly set about working over Bedell’s manuscript and soon brought it to a state of readiness for printing. When, like Bedell before him, Boyle sought a suitable Irish-character typeface for the printing, he too discovered that none was available and so he was obliged to have a new font of Irish type prepared for the purpose. Boyle describes this himself as ‘the letters I caused to be cast’, and later explained that ‘I caused a fount of Irish letter to be cast, and the book [the New Testament] here re-printed’. In the preface, Sall stated that:

‘God has raised up the generous spirit of Robert Boyle Esq. … who hath caused the same Book of the New Testament to be reprinted at his proper cost; And as well for that purpose, as for printing the Old Testament, and what other pious books shall be thought convenient to be published in the Irish tongue, has caused a new set of fair Irish characters to be cast in London, and an able printer to be instructed in the way of printing this language.’

Henry Jones, bishop of Meath, suggested that

‘If Mr. Boyle’s modesty would permit, I judge it necessary that at the end of the preface something be inferred concerning his bounty in the printing it at his own charges, that the nation may know their obligation to so worthy a benefactor’.

MODELLED ON LOUVAIN FRANCISCAN FONTS

Sall prepared the designs, which were modelled directly on the fonts used by the Irish Franciscans in their press at their college in Louvain. He was aware of their Counter-Reformation publishing efforts on the Continent. It was a rather astute move on his part, I would suggest, for the battle for minds waged between the printing presses of the Reformed church in Ireland and the Irish Franciscans on the Continent had a clear outcome—namely a preference for the type style of the Franciscans, which was modelled on minuscule manuscript handwriting, used primarily by the early scribes for writing Irish texts, while the style adopted by the establishment was based more on the uncial hand, used primarily for writing Latin.

Boyle turned to Joseph Moxon, a mathematician colleague and type founder trading in London, to prepare his type. Moxon too had been elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society (and coincidentally was born and died in the same years as Boyle). He was not particularly known for the excellence of his punch-cutting, but in this instance, sometime between 1678 and 1680, he cut a set of punches of small pica Irish characters (Hibernian) that accurately met Boyle’s requirements. Perhaps the relatively crude nature of the design helped to obscure his shortcomings in this regard.

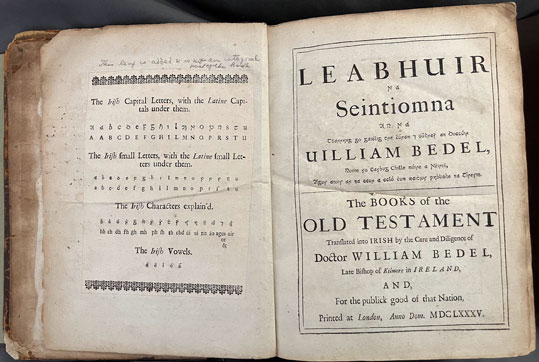

The type was used for the first time in 1680 by the London printer Robert Everingham to produce the catechism An Teagasg Criosduighe. It was used the following year for the second edition of William Ó Domhnuill’s translation of the New Testament and in 1685 for William Bedell’s translation of the Old Testament, for which purpose it had been prepared. Later, in 1712, it was used to print the Book of Common Prayer and, being the only Irish font available in Ireland and England, it became—to the limited extent that it was required—the standard for printing Irish text for over a century.

Robert Andrews succeeded Moxon in 1683 and the greater part of his foundry was made up of Moxon’s equipment. His foundry later passed to Edward Rowe Mores, having gone in the meantime through the ownership of Thomas James and his son John. Mores found himself the owner of a confused mass of punches and matrices, which included the Boyle/Moxon Hibernian. He commented that:

‘The Hibernian was cut in England by Mr Moxon for the edition of Bp. Bedel’s translation of the Old Testament in 1685, the only type of that language we ever saw. … The punches and matrices have ever since continued in England. The Irish themselves have no letter of this face, but are supplied with it by us from England.’

LATER ALTERATIONS

Mores’s foundry in turn passed by auction to Joseph Fry. The auction catalogue lists the punches of the Hibernian pica, describing them as ‘very good punches’, but the sample included in their 1794 specimen book shows significant alterations to the Moxon font of earlier use. It would appear that some of the characters may have been missing at the time of the sale. Consequently, Edmund Fry seems to have had new or borrowed sorts added to complete the font. These alterations led some observers to identify this new-look Moxon as a distinct so-called Graisberry type, since it was the Dublin printer Graisberry who made early noticeable use of the revised version.

Eventually the Fry works passed through the ownership of a number of foundries to that of Stephenson Blake and Co. Ltd of Sheffield in 1937. This foundry found itself in possession of some of the rarest print-related material dating back to the earliest days of punch-cutting in England. The Boyle/Moxon material remained in the foundry archive until the early 1990s, at which time it was finally accepted in an era of digital production methods that the commercial letterpress business of the foundry was no longer financially tenable.

Regarding the historic archive of punches, matrices, machines and specimen books etc., there was a real threat that the collection might be sold to an overseas buyer and steps were taken to block its possible export. With the support of the National Heritage Trust, the collection was secured and was assigned to the keeping of the Victoria and Albert Museum, being eventually placed by them in trust in the then newly established Type Museum in London—now named the Type Archive. After a brief period when the Irish material was worryingly unaccounted for, it was again reinstated there and confirmed to be present and in good order.

There is good reason, both in bibliographical circles and more generally in Ireland, to be interested in this important archive, since these Boyle/Moxon Irish punches represent the earliest extant examples known to have been produced in England.

Dermot McGuinne is the retired Head of the Departments of Fine Art and Visual Communication Design at the Technological University of Dublin.

Further reading

N. Canny, The upstart earl (Cambridge, 1982).

D. McGuinne, Irish type design—a history of printing types in the Irish character (Dublin, 2010).

E.R. Mores, A dissertation upon English typographical founders (ed. H. Carter & C. Ricks, reprint of 1778 edn) (Oxford, 1961).

T.B. Reed, A history of old English letter foundries (London, 1887).