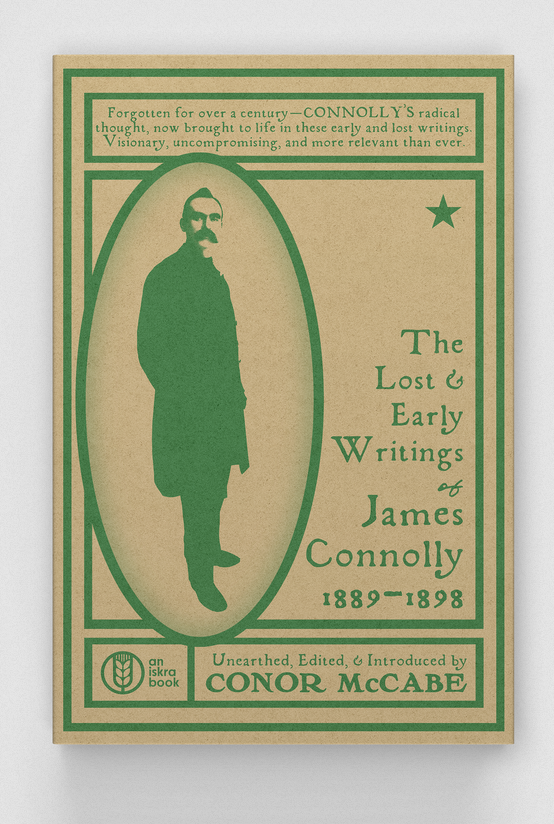

CONOR McCABE (ed.)

Iskra Books

€21.99

ISBN 9798330435210

REVIEWED BY

Emmet O’Connor

Emmet O’Connor is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Arts and Humanities at the Ulster University.

With over 1,000 publications on James Connolly, including a number of editions of ‘collected works’, one might think that his writings had been excavated exhaustively. Not only is this not the case but also hawk-eyed Connollyologists have sustained a running controversy on his bibliography. Conor McCabe, a veteran scholar whose publications have alternated between political economy and labour history over the past three decades, has shown characteristic courage in stepping into the ring.

The book is divided into nine parts, covering lost writings, lost fiction, lost letters, early writings never published, early writings previously published in part, early writings previously published in full, letters (mainly to his wife, Lillie, and Keir Hardie), secondary reports on Connolly (of interest for revealing what the contemporary press thought of him) and seven appendices. McCabe’s intent is to let Connolly speak for himself, and he avoids identification with any of the various factions aspiring to wear the great man’s mantle. Nor does he offer much in the way of biographical reinterpretation, except to say that Connolly’s brother John probably had a greater influence on him than has been supposed and to reject claims that fellow Scottish-Irishman John Leslie was a mentor. He does editorialise in four instances: a general introduction, introductions to parts 1 and 2, and an appendix on C. Desmond Greaves.

The most contentious part of the book will be the general introduction on the evolution of Connolly bibliography. As McCabe notes, since his martyrdom in 1916 there have been efforts to bend Connolly’s writings to prevailing ideologies. Up to the 1960s, clerics sought to square his Marxism with Rerum Novarum. More recently he has been invoked as a champion of immigration (he was anti-racist) or an opponent of immigration (he wanted Ireland for the Irish). McCabe’s Connolly is a man out to raise class-consciousness in everything he wrote, apart from his letters to Lillie. On the most controversial aspect of Connolly, his nationalism, McCabe accepts him simply, without contradiction, as both an international socialist and an Irish republican, with the one as stemming from the other. While this seems judicious to yours truly, there is no elaboration on Connolly’s thought and others might need more persuasion. Also controversial will be his comments on certain biographers, notably Donal Nevin and Desmond Greaves. The former is criticised for an amateurish compilation, and there is an unfortunate tradition in Dublin trade unionism of handing histories to amenable colleagues with time on their hands—ironic given the ancient animosity of craft unions to ‘colts’ or handymen. Nevin could be a menace. Regarding himself as a keeper of the flame, he actually discouraged research on Connolly and Jim Larkin. Greaves is slammed for not revealing his sources. In fairness to Greaves, he explained that he never used the usual scholarly apparatus, as he wrote to inspire and did not want his books to be judged on an academic basis. His biography of Liam Mellows, for example, declined to mention Mellows’s defeat in the 1922 general election. Yet Greaves has rarely been contradicted. In his final appendix McCabe goes to great lengths to refute Greaves’s claim that Connolly served in the British army. The chase is fascinating. The outcome is inconclusive.

So, what’s here and what’s new? McCabe includes all known publications of Connolly before the first issue of the Workers’ Republic on 13 August 1898, acknowledging that even in these digitised times there must be a few that have yet to be discovered. The collection contains eighteen previously unknown items, nineteen largely unknown accounts of his speeches, and seven appendices covering election campaigns and writings of John Connolly, who has hitherto lain in obscurity. Of particular interest will be James’s four lost works of fiction. Some of his creative writing is already known, and opinion on it is mixed. McCabe is largely positive on his creative ability, which does at least show him to be human, humorous, absolutely dedicated to the cause and able to mix all three traits.

There are some irritating lapses—surprising, given McCabe’s reputation for meticulousness. In the laziest of clichés, Connolly’s thought is described as ‘forgotten for over a century’, Keir Hardie is cited repeatedly as ‘Kier Hardie’ and the Public Record Office as ‘the Public Records Office’. Iskra’s production values are unvarnished. The bibliography is limited, the index of names is skeletal and there is no subject index. On the plus side, the presentation is clear, and author and publisher are to be congratulated for favouring footnotes (which are very informative and essential to the text) over endnotes.

Finally, one could quibble with some of the political interpretations. Connolly is credited with being the first Irish socialist to link the social and national questions. Okay, he was the first Irish socialist to do so, but the Labour movement had been doing it since the 1830s. Arguably, Connolly himself was colonised in the way he rejected the labour-nationalism of Irish trade unions, or in the way he sought to Hibernicise socialism just as British comrades tried to Anglicise socialism. But this is to go beyond the parameters set by McCabe and merely illustrates how Connolly is always a springboard for further discussion.

The lost and early writings is a wonderful addition to Connollyology and will be required reading for students of Ireland’s greatest Marxist.