By Fiona Fitzsimons

In May 1709, c. 13,000 Palatine refugees arrived in England. They were artisans and small farmers from the regions of Baden, Hesse and the Rheinish Palatinate (present-day south-west Germany). The Palatines were the crest of a wave, which by the time it receded had deposited over 30,000 refugees. They spoke many different dialects and belonged to different faiths, including Lutheran, Calvinist and Catholic churches (although at first the Catholic connection wasn’t public knowledge). The Palatines were fleeing war, religious persecution, bad harvests and hard winters. They arrived in England destitute; the death rate among them was at least 20%.

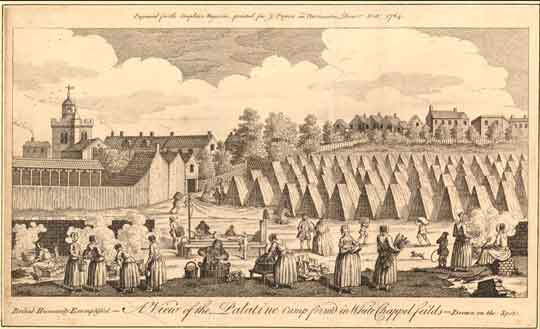

The government hastily set up refugee camps on the outskirts of London. At first the English public were sympathetic to their predicament. A public fund for the ‘Poor Palatines’ raised over £22,000 from the parishes and dissenter congregations. Public sympathy began to wane, however, when a government ‘census’ taken in the camps showed that about one third of all refugees were Catholic. They weren’t persecuted Protestants but economic refugees.

The Tories played the ‘race card’: immigration would bring in the ‘scum’ of Europe and would eventually ‘blot out and extinguish the English race’. The Whig government moved to resolve the crisis. They used the public monies raised to send the Protestant Palatines to America or, against their will, to Ireland. The Catholic Palatines were given the stark choice of converting or being repatriated to the Palatinate.

In Ireland, many landlords wanted to increase the number of Protestant tenants on their estates and granted generous leases to Palatine tenants. The original Palatine settlements were on the Southwell estate in Rathkeale, Co. Limerick (over 130 families), and the Ramm estate near Gorey, Co. Wexford (35 families), with smaller groups in Cork and Dublin. The land made available to Palatine settlers was marginal. After 30 years, when the original leases on the Rathkeale estate lapsed, many tenants couldn’t afford the higher rents. Between 1740 and 1755 they established new Palatine ‘colonies’, including four in Kerry: on the Blennerhasset estate in Ballymacelligott, the Crosby estate in Ardfert, the Sands estate near Sallowglen and Tarbert, and the Leslie estate in Kilnaughtin.

Palatines tended to marry within their own community and for generations they remained culturally and religiously distinctive. They worshipped within the Church of Ireland, responded to early Methodist preaching and formed Palatine Methodist societies at Ballingrane, Courtmatrix, Killeheen, Pallaskenry, Kilfinnane and Adare.

Emigration remained high—by 1760 between half and two thirds of all Palatines had left Ireland, most continuing west to the American colonies. By the late nineteenth century a distinct Palatine community in Ireland had largely disappeared, although we still find family names such as Jacob, Rhinehart, Sayers, Switzer and Tesky. The ‘hatch, match and despatch’ records of Irish Palatines can be found in the surviving registers of the local Church of Ireland parishes. Other secular records of Palatine colonies in Ireland survive in private hands, including minute-books concerning the division of land, individual agreements between members of the colonies, and account books containing details of ‘horse-rotas’ or the sharing of resources among the families. These records are rare name-rich survivals, especially useful for the early history of the Palatines in Ireland.

Fiona Fitzsimons is director of Eneclann, a Trinity campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.