RTÉ1, 15 and 22 October 2023 Midas Productions

By Sylvie Kleinman

‘It would take several lifetimes’ to consult all the records at the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), and more arrive every year. This two-part series, presented by Katie Hannon, is a relaxed but focused exploration of ‘stories’ about Ireland (i.e. the 26 counties) since 1922 that lie in the boxes and bundles of the NAI. Not driven by big history from above, it retrieves from official records episodes relating to issues such as housing, transport, tourism, foreign investment, film censorship and more. Hannon peruses reports, plans, memos or maps in the reading room familiar to many of us, but then draws us into backrooms or stacks (including the Four Courts) that the average researcher never gets to see. Technicalities of storage, conservation or digitisation are discussed, and a weighty Dickensian brass pulley still shuts vault doors.

Orlaith McBride, NAI director, provides impressive stats: the collection comprises c. 50,000 records which, quantified in linear form as per international practice, would stretch from Dublin to Kilkenny. The congenial Hannon then hits the road to visit specific locations around Ireland relevant to a given record, scenic or not. She chats with locals about the top-down impact of State initiatives on their daily lives, both successful and failed. Beyond the charm of a noble abandoned railway bridge overgrown with weeds on a dry summer’s day, the abandonment of the railway network in Donegal in the late 1950s is utterly dismaying. Local perceptions of the enduring success of an early housing estate in Clonakilty remind us of the emerging state’s commitment to make ‘the worst tenements in Europe’ history, though one would welcome corroboration of this via robust comparisons with ghettoes elsewhere in Europe.

Younger generations will reflect on the evolution to things we now take for granted, and The Records Show provides us with lots of nostalgia. Stunning shots of sun-drenched Donegal help us explore the modernisation of the country’s tourism infrastructure. Memories are still out there of holidaying c. 1968, when, according to a Bord Fáilte report, only 30% of hotel rooms had an en suite bathroom (but most places could boast a wash-hand basin!). Improvements, and menu planning, introduced a reviled profession that we shouldn’t only associate with British popular entertainment—the dreaded hotel inspector! In Bundoran, a phone network allowed hoteliers to ring around and warn that the ‘dreaded’ Mrs Kennedy was in town. But the successful hotelier Brian McEniff did state that she was good at ‘demanding standards, when standards were needed at the time’.

Department of Finance applications to the European Regional Development Fund led to ‘a fledgling’ US computer company’s first international base, in Hollyhill on Cork’s north side. The rest, of course, is history, and not only Apple’s. Great period footage reminds us of boxy computer monitors, how Ireland’s education system embraced badly needed IT training and that the fashions are back in style. The Industrial Development Authority was successful in inviting ‘industrialisation’ to Ireland, which fast became ‘a highly credible location for US investment’, while closer to home we entered the European common market. Ireland’s geographical location was an invaluable asset, which led to Shannon airport, conceived in 1935, becoming a major stopover for transatlantic flights. Its breakfast was pronounced ‘the best in the world’, though Marilyn Monroe chose an Irish coffee over Limerick sausage and bacon (no longer served on linen tablecloths). Reports pre-dating jet planes referenced a ‘psychological factor’, the opinion that landing on water in a flying boat was safer than on land. We saw the coastal spot for a planned anchorage basin, but land runways prevailed. There were great shots of glistening planes with the early Aer Lingus logos, and also the Knock story and building on a bog.

Some national and gender history is included. The NAI on Bishop Street being so near the former Jacob’s factory, we saw three fragments (green, white and gold) of the flag that ‘floated over it’ in 1916. Nation-building meant formalising the precise shades of green and orange in the tricolour, and the eventual choice of animals over patriots or religious figures on the first coins was deconstructed. Internal reactions to Mary Robinson’s landmark visit to Somalia in 1992, and her ‘emotional response’, led us to Iveagh House. Discussed there was the 1936 submission of the Joint Committee of Women’s Societies and Social Workers, requesting a meeting with de Valera. They were deeply concerned about the forthcoming Constitution and the decline of the status and rights of women since the foundation of the state, but to no avail.

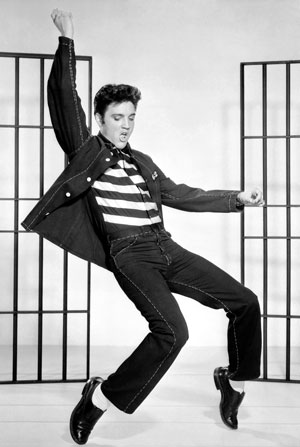

Philosophical but humorous, the Irish Film Classification Officer, John Kelleher, overviewed the chopping principles of the former Office of the Irish Film Censor. Casablanca, banned in 1943, was passed in 1945 but with ‘extremely significant cuts’ relating to the extra-marital love story between the characters played by Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart. Without their passionate embraces, Irish audiences could find ‘the meaning’ of the film ‘hazy’. Evidently, the ‘lascivious antics’ of Elvis Presley’s ‘abdominal dancing’ in Jailhouse Rock (1957) just had to go. But Ireland grew up, and the ‘guard dog’ role evolved into that of a ‘guide dog’. About 25,000 items survived the Four Courts fire in 1922, and the 1926 Census will be released in 2026.

Unpretentious, this programme is very informative and entertaining, does not overwhelm with highbrow academic perspectives, and clearly projects a deep sense of pride in how archives can inform the nation’s daily lives. Let us hope, then, that another compelling layer will soon be brought to our screens. The story of the survival of vital sources in the Records Tower in Dublin Castle, namely the Rebellion Papers and other series now in the NAI, is well worth a popularised visual retelling. Timothy Murtagh of the Virtual Treasury of Ireland team has ably reconstructed this recently (https://virtualtreasury.ie/archive-fever/edward-cooke-and-the-records-of-the-irish-chief-secretarys-office). Folk are still out there who researched or worked in what was the Irish State Papers Office, and capturing their stories of the awe-inspiring Tower will enhance what this documentary has started.

Sylvie Kleinman is Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of History, Trinity College Dublin.