by Seamus Heaney

Its former green is blue and thin,

And its once firm legs sink in and in;

Soon it will break down unaware,

Soon it will break down unaware.

At night when reddest flowers are black

Those who once sat thereon come back;

Quite a row of them sitting there,

Quite a row of them sitting there.

With them the seat does not break down,

Nor winter freeze them, nor floods drown,

For they are as light as upper air,

They are as light as upper air.

‘The Garden Seat‘ by Thomas Hardy

Hardy’s poem embodies a way of feeling and thinking about , the past which significantly amplifies our consciousness. It is about the ghost-life that hovers over the furniture of our lives, about the way objects can become temples of the spirit. To an imaginative person, an inherited possession like a garden seat is not just an object, an antique, an item on an inventory; rather it becomes a point of entry into a common emotional ground of memory and belonging. It can transmit the climate of a lost world and keep alive in us a domestic intimacy with realities that might otherwise have vanished. The more we are surrounded by such objects and are attentive to them, the more richly and connectedly we dwell in our own lives. Our place, our house, our furniture are present then not just as neuter backdrops but become influential and nurturing; our imagination breathes their atmosphere as rewardingly as our lungs breathe the oxygen of the air.

A moral force

It could even be maintained that objects which have been seasoned by human contact possess a kind of moral force; they insist upon human solidarity and suggest obligations to and covenants with generations who have been silenced. Consider, for example, this passage by the Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda. He is not explicitly concerned, as Hardy was, with the object as a capsule of the past, but he is testifying nevertheless to the power of the inanimate, its occasional aura of emotional and moral persuasiveness:

It is well, at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest. Wheels that have crossed long, dusty distances with their mineral and vegetable burdens, sacks from the coal bins, barrels and baskets, handles and hafts for the carpenter’s tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth. The used surfaces of things, the wear that the hands give to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things — all lend a curious attractiveness to the reality of the world that should not be underprized.

Pablo Neruda, Selected Poems (trans. Ben Belit)

Neruda’s declaration that ‘the reality of the world … should not be underprized’ implies that we can and often do underprize it. We grow away from our primary relish of the phenomena that influence us in the first world of our being. The rooms where we come to consciousness, the cupboards we open as toddlers, the shelves we climb up to, the boxes and albums we explore in reserved places in the house, the secret spots we come upon in our earliest solitudes out of doors, the haunts of our first explorations in outbuildings and fields at the verge of our security – it is in such places and at such moments that ‘the reality of the world’ awakens in us. These are archetypal moments, occurring in every life irrespective of intellectual, social or economic differences. And it is at such moments that we have our first inkling of past ness and find our physical surroundings invested with a wider and deeper dimension than we can, just then, account for.

This is an unconscious process at the time. It is neither sentimental nor literary, since it happens during the pre-reflective stage of our existence. It has to do with an almost biological need to situate ourselves in our instinctual lives as creatures of the race and of the planet, a need to learn the relationship between what is self and what is not self. It has to do with exploring, sniffing out, settling in and shaping up. And just as the smell of the rubber sheet in a pram or the feel of boards in the bottom of a cot or the scrape of the nappy pin as the child creeps on a tiled floor or the slippiness as he creeps over linoleum, just as these sensations teach the child about the realm of the present, so in every life there are sensations which inaugurate contact with the large and inviting reality of the past.

The top of the dresser

In my own case, the top of the dresser in the kitchen of the house where I lived for the first twelve years of my life was like a time machine. This was where all the old nails and screwdrivers and putty and lamp-wicks and broken sharping-stones would end up. Its mystery had to do with its inaccessibility, although to the mind of the adult — especially the adult in a rural farmhouse of the 1940s where concern with the development of the child’s sense of wonder was very far down on the agenda — there would be nothing mysterious whatsoever about the top of the dresser. It was a place where you could throw things out of the way, and that was that. But when I managed to climb up there, the yellowing newspaper on the putty, the worn down grains of the sharping-stone, the bent nails, the singed ends of wicks, the dust and stillness and rust all suggested that these objects were living a kind of afterlife and that a previous time was vestigially alive in them. They were not just inert rubbish but dormant energies, meanings that could not be quite deciphered. Naturally, I did not think this to myself at the time. It was all sensation: yet that sensation was tingling with an amplification of inner space, linked subtly and indelibly with the word ‘old’.

‘Old’ was not an idea. It was an atmosphere, a smell almost, a qualityof feeling. It brought you out of yourself and close to yourself all at once. ‘Old’ swam in the mind and senses when you came upon mossed-over bits of del ph or fragments of a clay pipe plugged up with mould. You took such things for granted where they lay about under dockens or at the backs of hedges: yet they swam across the screen of your awareness like strangenesses.

Another example of this expanding universe of the child’s mind: I knew more from overhearing and piecing together than from being told directly that a number of my father’s family had died in their teens and twenties from ‘the decline’ as tuberculosis was known in those days. Names of vanished uncles and aunts floated through the conversation. Johnny and Jamie and Maggie and Agnes. Agnes, I knew, had died young and an image of her invalid pallor which I had never seen was intuitively present to me, again because of her association with an object. This was a little trinket which was kept wrapped in tissue paper and laid away with other specially conserved knick-knacks in the bottom of the sideboard in my parents’ bedroom. I knew there was something slightly taboo about rummaging in those shelves but I was drawn again and again to unwrap the thing because I knew it had belonged to Agnes. It had obviously been bought at the seaside as a present for her. A little grotto about five or six inches tall, like a toy sentry-box, all covered over with tiny, fragile, pinkish, whitish cockleshells and mussel-shells, a pallid gleaming secret deposited in the sideboard like grave-goods in the tomb of a princess. To this day I cannot imagine the ravages of disease in that family in the 1920s without locating the sense of loss and hurt in the slight white fact of that grotto.

We read ourselves into a personal past by reading the significant images in our private world. That personal past is not necessarily determined by calendar dates or any clear sense of a time-scale. It is instead a dream-time, a beforehand, a long ago. We learn it by sensation, certainly without deliberate instruction, and the result of our learning is a sense of belonging to a domestic and at the same time planetary world of pure human being. There is, of course, another past that is not just inhaled naturally from our given environment but which is to some extent imposed, and to some extent chosen. This past gives us our cultural markings, contributes to our status as creatures conditioned by language and history. It is inscribed upon images that have a definite meaning and implication, unlike those other images whose meanings are personal and accidental.

An aura of the fantastic

If we begin with culture in the widest sense and think of the fairy tales we were told at home and at school, it will be obvious that these tales also conjure up a potent sense of the long ago and endow the world with a kind of legendary history. For example, there is a story I can now recall only in the vaguest way about a hen that panics and thinks that the world is going to fall in when a nut drops upon her out of a tree.

That tale gave a marvellous status to a corner of our yard where the fowl used to mould themselves in the roots of an old hawthorn. I kept looking in that place to make sure the sky was still in position, that no crack was appearing in the dome and that the hens were going about their business free from their version of nuclear terror. Another story about the man who grazed a cow on the grass growing upon a thatched roof invested certain old houses and wallsteads with an aura of the fantastic. The crock of gold we were told about at the end of the rainbow gave an extra dimension of possibility to those fields the rainbow shimmered above; and the story of the man shut beneath the hill with the fairy queen populated certain hills in the district with rare possibilities as well.

Fairy tale glamour

This fairy tale glamour was real but dispersed and impalpable. It had nothing to do with the sense of history, which began to be derived from books and pictures at around the same time. But the sense of history can also derive from special objects in the everyday surroundings. In our house there was an old, cock-hammer, double-barrelled pistol, like a duelling piece, fixed on a bracket above a door in the kitchen. It was a completely exotic item in that ordinary world of ash-plants, dressers, churns, buckets, statues and Sacred Heart lamps. It did not belong and it was never explained. Yet when I began to get comics and to read adventure stories, this pistol linked our kitchen to stagecoaches, women in crinoline skirts, men in ruffs, and duels at dawn in the woodlands of great estates. There it perched, unnoticed and ordinary in the eye of the adult, but for me radiant with an eighteenth- century never-never land. Not that this involved any great reverence for the thing itself. When my brothers and I grew up a bit, we got our hands on it and broke it in pieces inevitably, aCCidentally, but not very regretfully.

A man called wolf

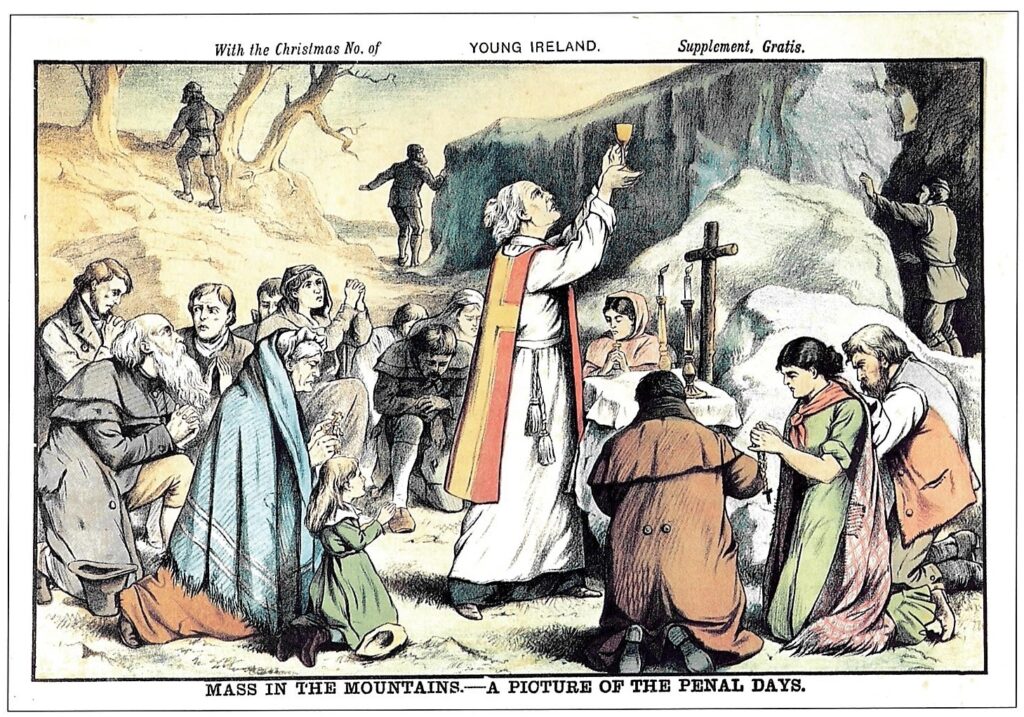

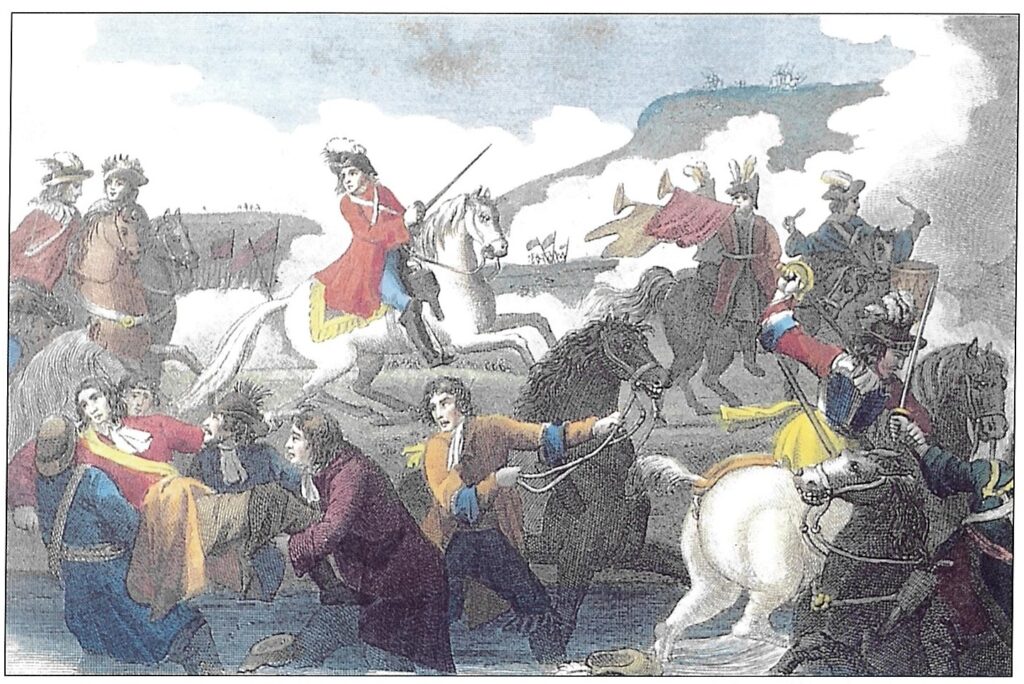

More generally interesting and more significantly influential than exotic items like the pistol, however, are those images and objects which Signify common loyalties and are recognised as emblems of a symbolic past which also claims to be the historical past. These emblems and objects guarantee our own way of feeling about ourselves as a group and as such they have a potent influence upon our everyday attitudes. I can think of no more apt illustration in this context than the picture of a mass-rock that used to hang in a neighbour’s house. This was once a familiar Sight, an oleograph of the outlawed priest in red vestments raiSing the host in a secluded corner of the hills, the hills themselves shrouded in snow, the congregation in shawls and frieze coats huddled around on one knee under the frosty sky, and away on the horizon, a band of redcoats coming into view over a crest of drifted snow. In between a man is running wild over the ditches to inform the congregation. In a way, nothing I have learned or ever could learn about the facts of the penal laws in Ireland could altogether displace the emotional drama of that picture. The eighteenth-century past will remain in some corner of my mind technicolour, panicky, frosty, arrested in whites and greys and scarlets. Just as Wolfe Tone will never quite escape from his reincarnation as the figure in tight-fitting white trousers and a braided green coat whose large profiled nose stared out above the audience during variety concerts in the local GAA hall. There he was, a given figure with a strange name, a man called wolf.

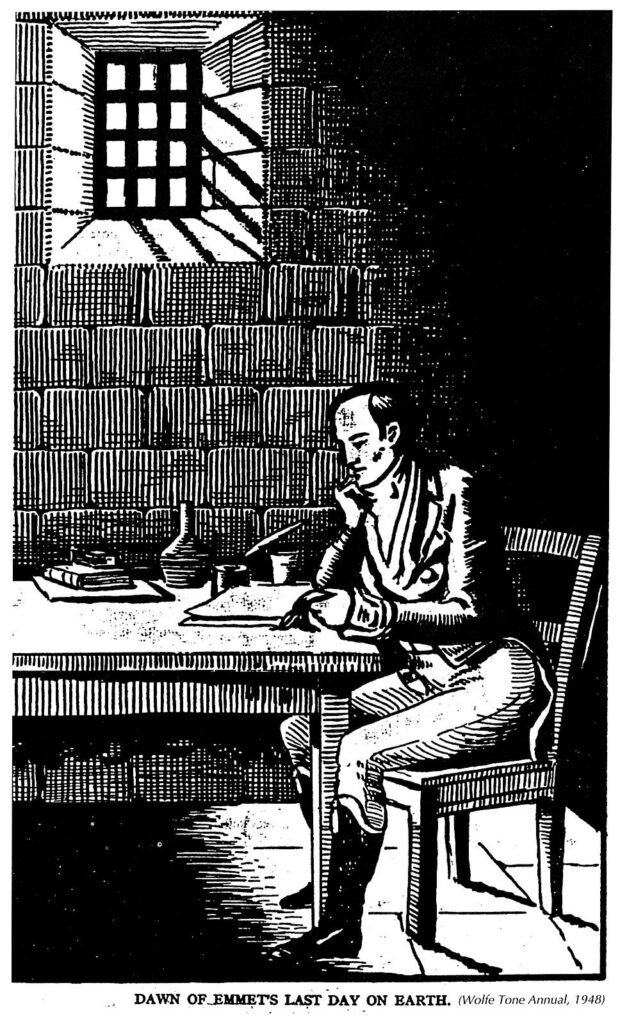

Similarly with Robert Emmet, this time as an illustration in an old Wolfe Tone Annual that I came across some time in the late forties; he was dressed in an open shirt and dark breeches, his arms folded, staring into a shaft of light that struck through his prison cell from a high barred window. Again, this image of a noble nature stoically enduring has had a deeply formative effect on my notion of the United Irishmen, the 1803 rebellion and the whole tradition of Irish nationalism. I do not mean that it closed my mind to any other notions but it offered a dream of the past against which all further learning took place and which, indeed, enhanced the learning process even when that process involved demystification and dismantling of the original image. Tone’s eloquent profile, for example, was not entirely eroded when I read Sir Jonah Barrington’s description: ‘His person was unfavourable — his countenance thin and sallow; and he had in his speech a hard guttural pronunciation of the letter R’.

We have been taught, and properly taught, to be wary of these idealising images of the political past because of the righteousness and simplifications impliCit in them, and the dangerous messianic arrogance which can flow from them. Yet emblematic scenes such as the mass-rock or Emmet in the dock or King William on his charger or Edward Carson signing the Covenant at Belfast City Hall are never as finally convincing as the authentic objects and documents which survive from the historical moment. No image of Hugh O’Neill, to take another powerful figure from the pantheon, no portrait of him with a strong Ulster face and Elizabethan clothes can get as close to our feelings and be as acutely suggestive of the real conditions of his life in the fort at Tullyhogue as this list of his abandoned possessions compiled by Sir Toby Caulfield in 1607:

2 long tables, 2 long forms, an old bedstead, an old trunk, a long stool, 8 hogsheads, 1/2 cwt. of hops, 3 hogsheads of salt, a silk jacket, 8 vessels of butter (containing 4 1/2 barrels), 2 iron spits, a powdering tub, 2 old chests, a frying pan and a dripping pan, 5 pewter dishes, a basket, a comb and a comb case, 2 dozen trenchers and a basket, a box, 2 drinking glasses, a trunk, one pair of taffeta curtains, another pair of green satin curtains, a brass kettle, 2 baskets with certain broken earthen dishes and some waste spices, a vessel with two gallons of vinegar, 3 glass bottles, 2 stone jugs whereof one broken, a little iron pot and a great spit.

We are back in a world whose reality we cannot easily underprize. The items on this list present themselves to us as a kind of braille over which the mind passes the tips of its understanding and sympathy in order to arrive at a reading of what lay behind the objects. The contemplation of such items functions for our good; human solidarity is reinforced by attention to the vestiges of a departed life. When we gaze at an ancient cooking pot or gaming board or the shoe of a Viking child or a medieval child’s drawing, we are exercising a fundamental and primary part of our nature. It is the part which cherishes human contact and human trust, which responds silently but contentedly when it discovers old initials carved on the rangewall of a bridge or in the bark of a tree.

The geniuses of the place

I have tried to distinguish two definite ways of being touched by the influence of the past. First, the intimate, almost animal, response of children to those elements in their first world which alert him to the mystery and claims of time past, and amplify and consolidate the sense of belonging to a family and a place. Second, I have looked too briefly at those images which widen this domestic past into a community or a national past, and have suggested how inevitably influential those images will be. And after that, when I came to the inventory of Hugh O’Neill’s possessions, I arrived at our third area of interest, material wrested from archaeology, history and folk life.

Breadth and refinement are two of the most desirable and valuable effects of education and our education towards these ends will be partly achieved by the contemplation of things mellowed by age. It will at least challenge a too narrow conception of loyalty and solidarity, and emphasise the truth of the old catechism definition of who our human neighbour is: ‘My neighbour’, said the catechism with resonant simplicity, ‘is all mankind’. So I think of my mesolithic neighbour from Ballyscullion, and of his flint flakes, spearheads and arrowheads which were found in abundance at New Ferry during the Bann Drainage Scheme. Seeing these on display in the Ulster Museum once gave me a vision of those first hunters among the rushes and bushes at the lower end of our parish, and I thought of them as being at one on the land with the farmers, clayworkers, fishermen, turf-cutters and duck-shooters who were the geniuses of the place when I first got to know it.

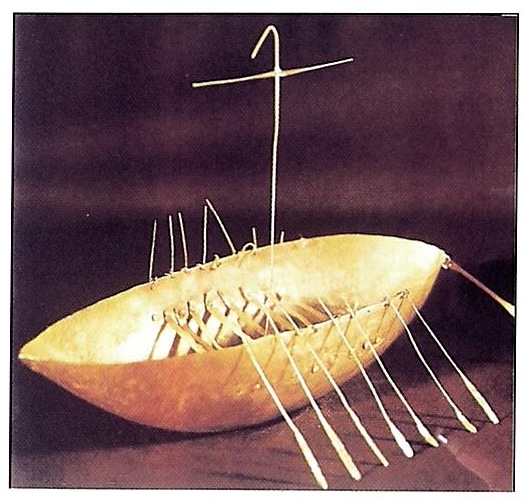

That time-scale, that double sense of great closeness and great distance, subtly called into question the factional and sectarian closenesses and distances which have been pervasive in that part of the country. I do not say that a sense of the mesolithic ancestor could solve the political problems of the Bann Valley but I do say that it could widen and clarify thelens through which we inspect the question of who we think we are. Similarly with that magnificent hoard of gold objects found in County Derry and now held in the National Museum as The Broighter Hoard’: to gaze at those arm-bands, gorgets and lunulae, so silent, solid and patiently beyond us, is to be displaced from one’s ordinary sense of what it means to be a County Derry person. The gazer is carried a little out of himself, is transported for a moment into a redemptive mood of openness and readiness.

Sensitivity to the past contributes to our lives in a necessary and salutary way. It is not just a temperamental or intellectual accident, like a talent for chess or a paSSion for whiskey, but a fundamental human gift that is potentially as life-enhancing and civilising as our gift for love. Indeed it can be said without exaggeration that the sense of the past constitutes what the poet William Wordsworth would have called a ‘primary law of our nature’.

Seamus Heaney is Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University.