RTÉ1, 31 July 2023 Directed by Alan Gilsenan

By Brian Trench

In the opening clip of this documentary, Noël Browne is a guest on RTÉ’s Late Late Show and the host, Gay Byrne, takes a call from a woman who confesses that she once tore down Browne’s election posters on the urging of the nuns who told her and her schoolmates that Browne was a communist. The caller came to regret her action and to admire Dr Browne as one of the few honest politicians. He responds awkwardly, offering his forgiveness. The caller says that she was happy to vote for him subsequently. He murmurs, ‘Thank you’.

The short sequence neatly encapsulates the central themes of the documentary, showing Browne as both reviled and revered, but also aloof. There are recurring images of Browne walking alone in the lanes around his Connemara home, including in the closing sequence of the documentary. He explains the choice of this place in terms of its isolation. His daughters describe him as a loner.

And yet in an RTÉ interview in the 1960s he declares himself to be a revolutionary socialist and in other clips to have sought to change the system. This would be generally regarded as collective work, but the only comrade acknowledged—and repeatedly—was his wife of 60 years, Phyllis. When Browne uses ‘we’ in reference to his public life he is speaking of himself and Phyllis.

In director Alan Gilsenan’s choice of interview clips, Browne names only one other political colleague, Jack McQuillan, who was a well-grounded foil to Browne’s more lofty self. We get very little sense of how Browne was so successful electorally, and none of any other activists who worked with him. There are still images of Browne at conferences, though only one video clip of him as a public speaker. This may be Gilsenan’s way of representing Browne as Browne saw himself.

Browne’s first two of his seven ages, as child and young adult, take up the first third of the documentary. This experience of poverty, illness, emigration and his parents’ and oldest sister’s early deaths are profoundly affecting, not least because of Browne’s abiding admiration for the heroic efforts of his mother and sister Eileen to save the family from an even worse fate. He recalls these days in clips from a previously unseen interview recorded in his last years (apparently in 1994, though neither this nor other interviews, or still images, are captioned with dates or sources). Sixty years after the events, he struggles to get the words out about how his widowed mother died just days after she had got the children to London in a desperate bid to keep them together.

Noël not only survived all this but also became the beneficiary of a ‘miracle’ in the form of patronage from wealthy Catholic families that got him to private schools in England and to Trinity College, Dublin, to study medicine. This could not protect him from his own family’s scourge of TB, however, though that was the occasion of another near-miracle. Despite his illness, the fellow student with whom he had fallen in love, Phyllis Harrison, stuck with him. His retelling of these stories is as filled with gratitude and happiness as it is with sadness and anger. His family experiences also affected his outlook, as he explained in a 1960s RTÉ interview. He came to see that ‘God and his holy mother … had an insatiable appetite for human suffering’. That was, at least in part, the basis of his political activity.

The middle third of the documentary covers Browne’s election to the Dáil in 1948 and his immediate appointment as minister for health in the inter-party government. The three years of his ministry take up more time than the 24 further years of his membership of the Dáil and Seanad. Browne was an exceptional parliamentarian, but we get no flavour of his contributions to debates or to legislative proposals.

Reflecting on his time as minister in the 1994 interview, Browne describes the experience as an enormous privilege, and he accepts that ministers must bear responsibility for the effects of their actions. He proudly and justifiably claims significant success in the building of hospitals and the near-elimination of TB, but the episode that has given him legendary status was tense, conflictual and ultimately disillusioning. His proposals for a free-access health scheme for mothers and children met determined opposition from the Catholic hierarchy and the leadership of the medical profession. Losing the support of his own party, Clann na Poblachta, and of the government, Browne had no option but to resign. He remains to this day a martyr in the cause of secularism and public health service.

In a series of cleverly presented short clips from a retrospective interview, his party leader Seán MacBride is heard to praise himself for appointing Browne, to acknowledge Browne as a very good minister, and then, in increasingly snippy manner, to say that he had not informed himself sufficiently, that Browne became more and more irresponsible, and succeeded in establishing his version of events as authoritative.

Browne survived the political marginalisation perhaps better than his ostracisation by the medical profession and scaremongering by the church. The orientation of the documentary to his personal and family story gives us insights into the impacts of ‘the medical people [seeing that] I wouldn’t work’ and of the deeply divided opinion around him that led his daughters to keep quiet about his being their father. Browne chose a winding path, retraining in psychiatry in order to work in publicly funded, though initially poorly remunerated, positions.

Susan and Ruth Browne recall their father as ‘a terrible worrier’—with every reason, as they say—but also in other moments as a very happy person who enjoyed going to the cinema with them (Bonny and Clyde, The Godfather), a husband who ‘just adored’ his wife, Phyllis, and a loner who ‘loved the sea’.

These clips and the 1994 interview, which provides the documentary’s backbone, convey an image of someone with a deeply troubled past and a calm present who does not care much about how he is remembered. Nevertheless, his legacy remained important to him. When a group of us came together in the mid-1990s to have a statue of James Connolly erected in Dublin, Browne took exception to the description of this initiative as the first memorial in the city to Connolly. In a rather curmudgeonly manner, he wrote to the Irish Times to recall that one of the hospitals built under the programme he led was, indeed, the James Connolly Memorial Hospital.

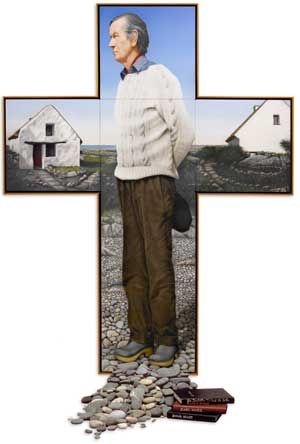

This documentary introduces a new generation to a remarkable figure in Irish public life and adds layers of intimacy and complexity to the known story. It eschews assessment of Browne by biographers, historians, political commentators or even in the form of his portrait by Robert Ballagh. This depicts Browne with the cottage behind him and sea-rounded stones at his feet. It is presented in cruciform.

Brian Trench was a senior lecturer in the School of Communications, Dublin City University; he was assistant general secretary of the Socialist Labour Party when Noël Browne represented that party in the Dáil.