By Brian Hanley

Speaking in Leinster House in May 1959, Richard Mulcahy, the IRA’s War of Independence chief-of-staff, quoted a recent study by the British historian A.P. Thornton. Thornton’s The imperial idea and its enemies had asserted that ‘the case of Ireland made it clear to everyone that the British Empire could no longer be assumed to stand foursquare on a basis of unchallengeable power. For the Sinn Féin movement had challenged that power, and had challenged it successfully.’ Thornton argued, however, that republicans had not done this by ‘superior military force’ but because holding Ireland would have required ‘the tactics of Strongbow, Essex and Cromwell combined’ and, while Britain had bigger forces ‘at her disposal (than) Cromwell had possessed’, employment of these tactics was not ‘a practicable imperial policy’. There has been a tendency, in popular commentary at least, to imagine that Michael Collins and the IRA had succeeding in ‘forcing the British Empire, not just to a truce, but to its knees’. Though Collins himself thought that idea ‘pathetically absurd’, Arthur Griffith still hailed him at the time as the man who ‘won the war’. But who had ‘won’ in 1921?

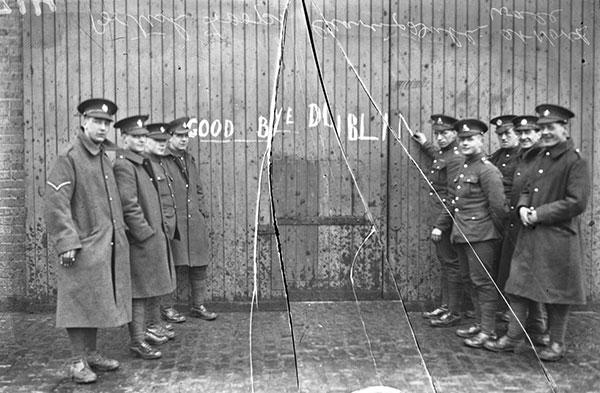

During the Treaty debates Eoin O’Duffy promised that soon ‘the British soldier and British peeler will never again be seen in Ireland’. As Truce liaison officer in Belfast and proponent of aggressive action along the border, O’Duffy knew well that the British military were only leaving part of the country. Nevertheless, for many it was a persuasive argument. We forget too easily what a militarised society Ireland was prior to independence. The barracks dotted across the country were the most obvious expression of British rule. At any one time there were up to 30,000 military personnel stationed here. The military were so interwoven into everyday life that their withdrawal was a dramatic illustration that something indeed was changing.

Under the Treaty, however, Britain still maintained naval bases in the Free State (making neutrality impossible) and insisted on the inclusion of provocative symbols, such as the Oath. Most obviously, British military power underwrote partition. The Treaty was an agreement crafted by the British, which Irish delegates were ultimately forced to sign under threat. Dublin in 1922 was not Saigon in 1975 or even Kabul in 2021. The British army left in good order, taking their documentation and equipment (apart from that supplied to the Free State) with them. And the British threat of war poisoned the agreement and made renewed violence likely.

Nevertheless, many of those who rejected the Treaty did so because they did not believe that Britain could go back to war. The republican periodical Old Ireland noted in August 1921 that it was

‘… perfectly evident that what turned England towards peace was that it seemed to her that she had more to gain from peace than from war … The IRA has caught her at a time when her international position is anything but secure, when her Empire, vaster than ever, covering more of the map, is yet capable of very quick disintegration. That is the whole secret of it … She can go to the Washington Conference with Ireland still at war with her, but she would rather not. That is all. For once the stars in their courses have fought for us: for once we hold the whip hand.’

This was perceptive, if perhaps over-optimistic, about how global affairs influenced British thinking. Indeed, several anti-Treatyites, such as Harry Boland, asserted ‘that there can be no war in Ireland’, as Britain’s imperial commitments made reintervention impossible. Boland also warned, in words echoed again by several of his comrades, that accepting the Treaty would place the Free State on Britain’s side against Ireland’s allies in India and Egypt. (Indeed, on evacuating Ireland some 4,000 British troops were sent directly to both countries.) Arthur Griffith responded that, while he sympathised with the ‘poor Egyptians and the poor Indians’, his primary concern was with ‘my own countrymen first’. Egyptian nationalist Makram Ebeid feared that Ireland’s status as a beacon for struggling nationalities would be compromised by acceptance, while Indian communist Shapurji Saklatvala denounced the Treaty as ‘based upon coercion’. In contrast, black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey rejoiced that the Irish had ‘succeeded, first among the trio of Egypt, India and Ireland, in winning a place of mastery among the nations and races of the world’.

British ‘die-hards’, for their part, saw the Treaty as a surrender to ‘terror’, unionist historian W. Alison Philips describing it as ‘the greatest humiliation which has ever fallen upon a proud and ancient people and Government’. A settlement with those only recently dubbed a ‘murder gang’ clearly did involve very public compromise on the part of the British establishment, but it was possible for them to argue that it was done from a position of power. As Sir Samuel Hoare put it, the British Empire was ‘so strong that we can make big and generous concessions’. The more far-seeing among the British élite thought that there were potential benefits in placing the onus for solving the ‘Irish Question’ on the Irish themselves. Lloyd George suggested that, ‘for the first time in the history of our treatment of Ireland, if the Treaty is broken by Ireland, the civilised world will say England is blameless’. This perception in turn ‘would be invaluable if the time [to reinvade] ever came’.

Many republicans instinctively opposed the idea of ‘voluntary’ membership of Empire, something never previously conceded by most Irish nationalists. As they pointed out, Ireland was not Canada or New Zealand, settler colonies where a majority still looked to Britain as the ‘mother country’. While significant for republicans, however, such questions may have seemed abstract to a population eager for peace, for whom the withdrawal of British forces was evidence enough that some kind of ‘victory’ had been achieved. The popular movement around that goal was arguably already demobilised by the Truce. Many people assumed that ‘peace’ was to be permanent. Despite the confidence of local IRA commanders, going back to war was not likely to be easy. A popular movement could not be turned on and off like a tap. The IRA had depended on civilian support expressed through strikes, boycotts and the construction of an alternative administration. The IRA recruited widely during the Truce but Seán Moylan would later bemoan how the behaviour of some Volunteers earned it ‘a reputation for bullying, insobriety and dishonesty that sapped public confidence’. While republicans had generally exhibited benign neutrality towards industrial struggle before the Truce, during it the IRA was increasingly used against striking workers. The consequent alienation of organised labour would be costly, but it suggested that most TDs, despite differing views on the Treaty, shared common assumptions about how people should not be ‘diverted from the struggle for freedom by a class war’. By 1922 a left-wing journal would contend that ‘a big percentage of the Irish are apathetic to the struggle; this is particularly true of the landless peasants and the workers in the cities and big towns’. Going back to war would not have brought the IRA automatic public support.

A popular revolutionary effort required more than new equipment, as illustrated in the way in which the anti-Treaty IRA, far better armed than their pre-Truce predecessors, were defeated relatively quickly by Free State forces in conventional warfare during the summer of 1922. Those opposing the Treaty had high hopes that international opinion would stay Britain’s hand, but there was no major power practically willing to back Irish resistance to what was perceived as a generous settlement. The Irish diaspora, too, generally saw the Treaty as an acceptable compromise and were demoralised by the bitterness of the split in Ireland.

Nevertheless, the United Kingdom had lost proportionately as much territory as did Germany after Versailles. Its ability to rule its oldest colony had been destroyed by a popular movement that provided inspiration for oppressed peoples across the globe. The British Empire could no longer rule in the old way. Surely that did represent a victory against the odds and is something still worth celebrating?

Brian Hanley lectures in Irish history at Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

S. Donnelly, ‘Ireland in the Imperial imagination: British nationalism and the Anglo-Irish Treaty’, Irish Studies Review (2019).

M.C. Rast, ‘“Ireland’s sister nations”: internationalism and sectarianism in the Irish struggle for independence, 1916–22’, Journal of Global History (2015).