By Andy Bell

‘The first Welsh-language radio broadcast was made from Dublin.’ That surprising and incorrect assertion came from not one but two governments in the Ireland–Wales Shared Statement and Joint Action Plan 2021 to 2025. Both the Dublin and Cardiff governments had misconstrued a single event and, in so doing, belittled a far more significant episode in broadcasting history.

WELSH IGNORED BY THE BBC

What 2RN, the Dublin broadcasting station, did do in the mid-1920s was to give due regard to the Welsh language and culture at a time when the BBC was doing its level best to avoid anything of the sort. The 1921 census showed that 922,100 people spoke Welsh—37.4% of the population of Wales. The rest of the UK went unquestioned about proficiency in Cymraeg, but it is fair to assume that the total number of Welsh-speakers across the UK exceeded one million. Despite those numbers, which included tens of thousands with little or no English, the BBC baulked at providing any kind of service in the language. Any Welsh content that they did broadcast was irregular and music-based and was transmitted under sufferance following pressure from cultural nationalists. The manager of the BBC’s Cardiff station 5WA, E.R. Appleton, remarked that the occasional provision of ‘A Welsh Hour’ on his airwaves had displeased many listeners. ‘The “Hours” have been considered not quite cheerful enough and … our English-speaking audience simply switches off’, he sneered.

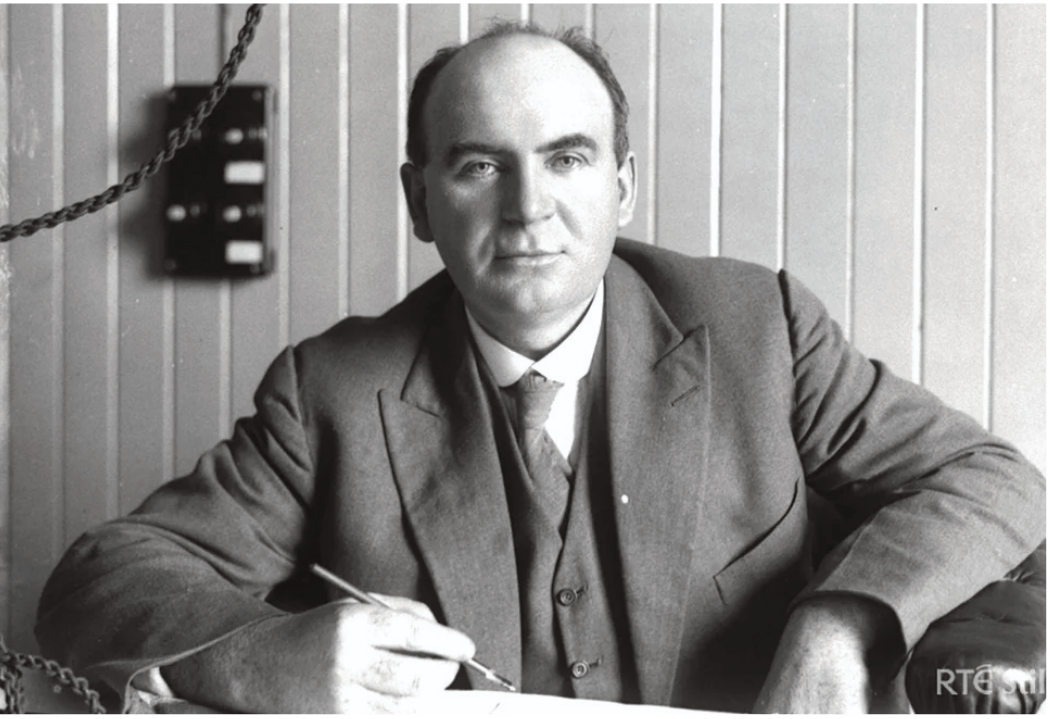

Seamus Clandillon, 2RN’s first director, had a vastly different world-view. This passionate supporter of traditional music told listeners that he wanted to make 2RN ‘a rallying centre for Gaelic culture at its best, in which Ireland, Wales, Manxland, Scotland and, later perhaps, Brittany, would present their most characteristic art to the listening public of these and other lands’.

With that in mind, 2RN first provided a platform for Welsh content and then regular programmes featuring the Welsh language. ‘Ever since its inauguration the Dublin Broadcasting Station has included occasional Welsh items in its attractive programmes’, purred the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald in February 1927. Its sister paper, Yr Herald Cymraeg, noted approvingly that ‘Gorsaf Dublin yw’r orsaf fwayf Gymreig yn awr, ac ni chaiff Dublin yr un geiniog o Gymru’ (‘The Dublin station is the most Welsh now and Dublin does not get a single penny from Wales’).

‘DUBLIN CALLING’

There had been great excitement in the UK for 2RN from its inception in January 1926. Under the headline ‘Dublin calling’, the Manchester Evening News reported Clandillon as being pleased most with ‘the spontaneous expressions of appreciation which he has received from so many people across the Channel’. Holyhead, Caernarfon, Penmaenmawr and Aberystwyth were among the locations of those fans. A Mr W.B. Thomas of Park School, Holyhead, concluded his congratulations with the following message in Welsh: ‘Da iawn yn wir. Llwyddiant i chwi’ (‘Very good indeed. Success to you’). Within months that enthusiasm was rewarded with programmes featuring Welsh choral music, ballads and folk-songs. Most, but not all, of the singers came from Anglesey in general, and the ferry town of Holyhead in particular. ‘Miss Ceinwen Rowlands was heard to good effect on the radio broadcast from 2RN (Dublin) on Friday night’, enthused the Holyhead Mail and Anglesey Herald in late August 1926.

Alongside these recitals there were talks. In December 1926 Professor John Lloyd Jones, the first Professor of Welsh at the National University of Ireland, spoke about ‘The Welsh Eisteddfod’. Those efforts moved up a considerable notch in February the following year when 2RN broadcast what we would now call a ‘pilot’ programme. W.S. Gwynn Williams, a musician and composer who went on to help establish the Llangollen International Eisteddfod, lectured for half an hour on Welsh folk music. Then, after an orchestral interlude, he returned with the ever-popular Ceinwen Rowlands for 30 minutes of actual song. It was deemed a success and sparked ambitious plans.

‘ST DAVID’S DAY SPECIAL PROGRAMME’

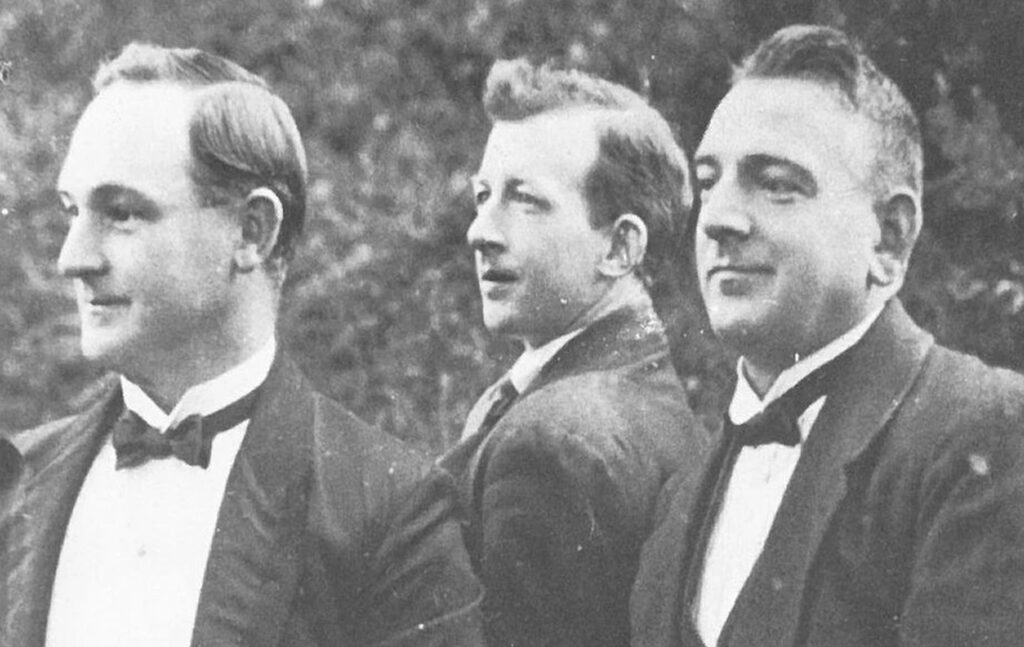

‘The announcement that 2RN intends to broadcast a monthly Welsh programme has evoked favourable comment on this side of the channel’, reported the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald. Those broadcasts officially started on Friday 4 March 1927 with a ‘St David’s Day Special Programme’. The 90-minute-long broadcast starred Y Brodyr Francis (the Francis Brothers), who were hugely popular in north Wales and were supported by their pianist, Bob Owen, and noted contralto Gwladys Williams. Griffith and Owen Francis hailed from Dyffryn Nantlle, a slate-quarrying heartland of the Welsh language south-east of Caernarfon. Dr Ffion Owen’s research into the area’s history unearthed some nuggets about this broadcast. She told my Rhaglen Cymru podcast that W.S. Gwynn Williams had written to the Francis brothers soon after the February show on 2RN, inviting them to travel to Dublin. The pair were urged that ‘Byddai’r darllediad yma yn deffro yr awdurdodau Prydeinig i’w dyletswydd i ddarlledu cyfrwng Cymraeg’ (‘This broadcast would awaken the British authorities to their responsibility to broadcast through the medium of Welsh’).

The response to the March broadcast was huge. Radio receivers were not common in rural areas at that time, but wherever there was one there were crowds of people listening in. ‘Clywyd yn eglur ac effeithiol’ (‘They were heard clearly and effectively’), reported Yr Herald Cymraeg. Ffion Owen told Rhaglen Cymru that one local, who was just five years old at the time, recalled the community as ‘walking on air’ after hearing the programme. And a contemporary correspondent to the Holyhead Mail was equally enthusiastic, writing: ‘I respectfully suggest to the Holyhead Cymrodorion that they forward a letter of thanks to Dublin as a mark of their appreciation of the thoughtfulness on the part of those in charge of the Irish station’.

And there was, perhaps inevitably, poetry to celebrate the ‘Special Programme’. Yr Herald Cymraeg asked its readers to compose a verse after proffering an opening line. The winner of the competition captured the excitement of the moment:

Ar y wireless o Dublin

Fe ddaeth sain pennillion telyn.

Y Brodyr Francis oedd yn canu

Padis filoedd yn rhyfeddu.

Clywed dau o arwyr Arfon

A’u Cymraeg yn llanw Iwerddon.

Ond pa ryfedd iddynt synnu,

Dyma brif ddatgeiniaid Cymru.

On the wireless from Dublin

Came the sound of harp and verses.

The Francis Brothers there were singing,

Paddies in their thousands were astounded.

Two of Arfon’s heroes heard

And their Welsh filling Ireland.

But that was no surprise

As these are Wales’s finest singers.

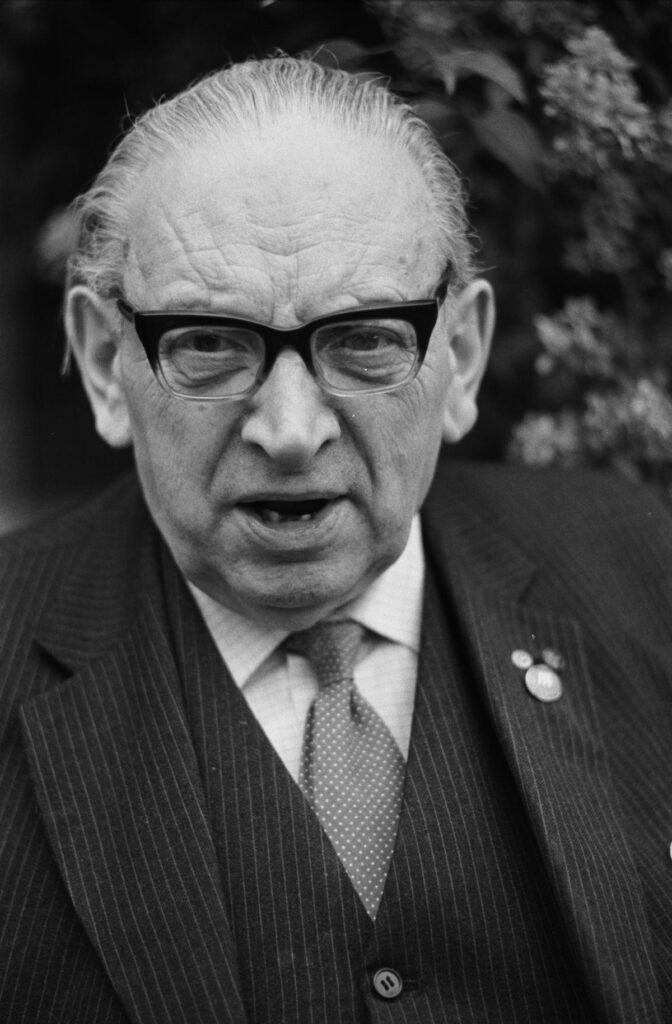

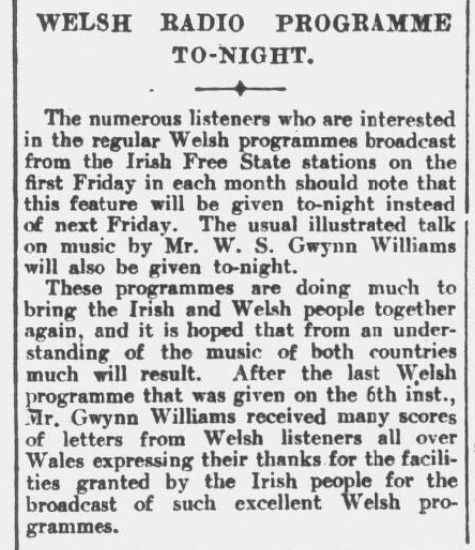

There followed monthly programmes on 2RN of song and occasional Welsh lessons for the next year and a half, with W.S. Gwynn Williams at the helm.

In March 1928 a columnist in the Dublin Leader wrote: ‘It is refreshing to hear nationality in music treated of as he treats it. In Ireland we have been accustomed to have the native element in Irish music quietly pooh-poohed.’ And the writer was very clear about the linguistic nature of the programmes: ‘Mr Williams, although he lectures in English, talks, as far as I heard him, only Welsh about his concert items’.

BBC EMBARRASSED INTO ACTION

Williams and Clandillon quickly succeeded in embarrassing the BBC into begrudgingly recognising the linguistic reality in Wales. The corporation’s Cardiff station finally lifted its ban on spoken Welsh, and it utilised the high-power Daventry transmitter in the English midlands to reach the whole of Wales, as it followed Dublin’s example by having a regular ‘slot’ for programmes. Remarkably, even the BBC’s weekly magazine, the Radio Times, boosted 2RN’s efforts. It reported that ‘… the first Friday of each month is devoted to an all-Welsh programme in the Welsh language, in which appear prize winners at the various Eisteddfodau’. The magazine also noted that ‘on completion of the work in progress towards the renovation of the old General Post Office, palatial quarters will be at the disposal of staff and artists’—but not of the Welsh programme. It disappeared during the summer of 1928, a few months before the move to the GPO.

There was no formal announcement, but various articles in the Welsh-language press strongly suggested that maintaining the monthly concert was becoming challenging, financially and practically. The Herald Cymraeg pleaded with its readers to show their support, predicting that without it there was no certainty that the programmes would return in the autumn. ‘Da fyddai i bawb sydd eu gwrthfawrogi anfon gair i’r perwyl hwnnw i reolwr gorsaf Dublin’, it urged. (‘It would be good if all those who enjoy these [programmes] send a message to the Dublin station manager to that end.’) But no further programmes under the direction of W.S. Gwynn Williams were heard.

Welsh did not entirely disappear from 2RN. Some Welsh lessons were broadcast in 1929, and irregular concerts of folk and choral music—‘Welsh Airs’—thereafter. And as late as July 1954 there were pleas for the return of the ‘Rhaglen Gymraeg’. Fianna Fáil TD Michael J. Kennedy told his fellow deputies that ‘I have advocated that we should have a Welsh half-hour. That would do immense good in this country in improving our choirs and our taste for music.’

By the mid-’50s the BBC, and soon ITV, were building a relatively strong Welsh broadcasting culture, based on their own creativity and frequently prompted by external demands. Indeed, the political battle to get the Welsh language on the airwaves went on for decades, with petitions, endless committees and law-breaking protests. That campaign culminated in 1980 when a nationalist leader, Gwynfor Evans, threatened to starve himself to death unless the UK government of Margaret Thatcher honoured its election pledge to establish a Welsh-language TV channel. Evans stared down Thatcher and won a notable victory. Sianel Pedwar Cymru went on air in 1982, fourteen years before Teilifís na Gaeilge (now TG4).

Back in the 1920s, Seamus Clandillon needed no threats to give Welsh a place in broadcasting. He merely responded positively to a polite request. The UK government’s 1927 report Welsh in Education and Life indicates just how important Clandillon’s contribution was: ‘It is a rather pathetic comment on the position of Welsh in its own country that the only regular Welsh programmes are given once a week from the Dublin Station by the Irish Government’. While those sentiments, just like the Ireland–Wales Shared Statement and Joint Action Plan almost a century later, got the fine detail wrong, they were rock-solid on the significance. Seamus Clandillon deserves a special place in Welsh history.

Andy Bell is a broadcaster and podcaster based in Australia, previously based in south Wales.

Further reading

J. Davies, Broadcasting and the BBC in Wales (Cardiff, 1994).

J. Gower, The story of Wales (London, 2013).

M. Johnes, Wales: England’s colony? (Cardigan, 2019).