By Angeline O’Neill

The story of The Wild Goose, the Catalpa and The Pilot is the story of Irishman John Boyle O’Reilly, a Fenian convict who became one of the most powerful journalists in the United States in the nineteenth century. His writing ranged from the production of a handwritten newspaper, The Wild Goose, by a group of Fenians on board the last convict transport to Australia in 1868 to a multitude of editorials and articles appearing in The Pilot, a Boston newspaper edited and eventually part-owned by O’Reilly.

Historian Peter Vronsky has suggested that ‘whether the Fenians were rebels, patriots, assassins, freedom fighters, murderers, martyrs, national revolutionaries or terrorists, depends much upon their historical chronology and an observer’s point-of-view’. The Fenians were founded in the late 1850s by Young Ireland rebels James Stephens and John O’Mahony with the bringing together of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and the Fenian Brotherhood. Their goal was the creation of an independent Ireland free of the British Crown. According to Vronsky, they were arguably the first modern transcontinental national insurgent group in the western world, with operational cells in Ireland, England, Canada, the United States, South America, New Zealand and Australia. Among their number was John Boyle O’Reilly.

BACKGROUND

O’Reilly was born in 1844 in Drogheda, the second son of William David O’Reilly, master at the national school at Dowth Castle, and his wife Eliza Boyle. He was educated by his father, apprenticed at eleven to the local newspaper and at fifteen joined the Manchester Guardian in Lancashire, where he became a reporter. O’Reilly’s family was fiercely patriotic, and young John was to become a journalist, poet and human rights activist.

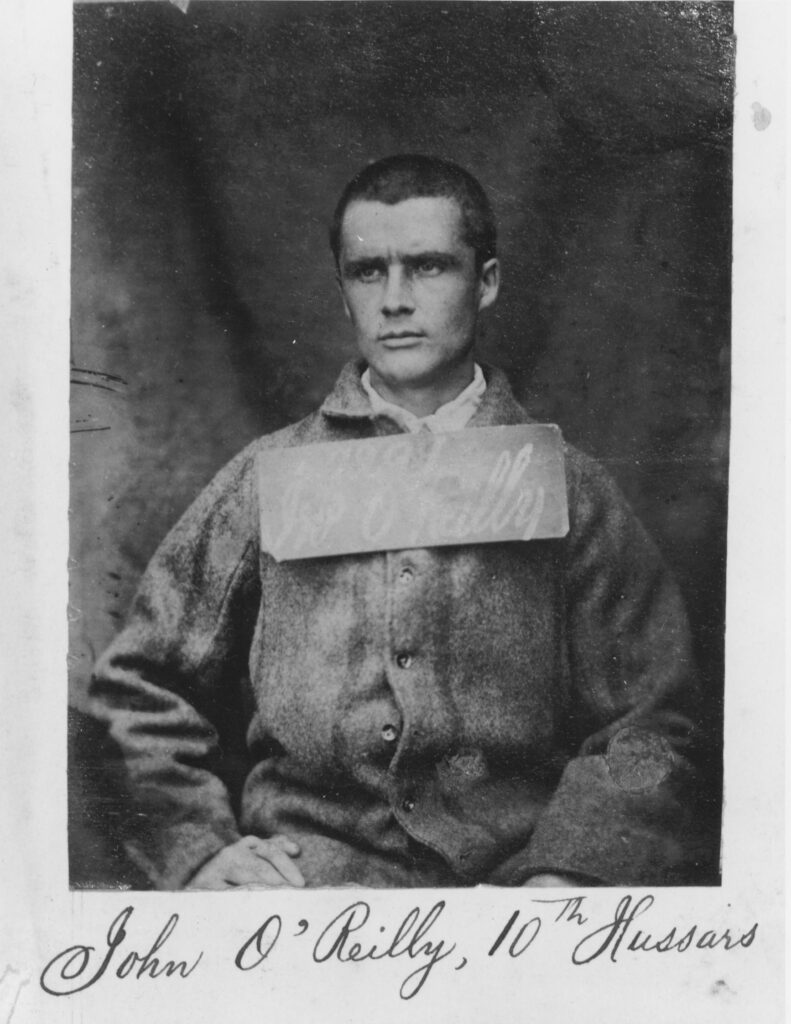

In June 1861 O’Reilly enrolled in the 11th Lancashire Rifle Volunteers, with whom he received some military training. In 1863 he returned to Ireland, where he enlisted with the 10th Hussars in Dublin. Sometime in 1865 he joined the IRB. While in the British army, O’Reilly lived a double life as a recruiter for the IRB within his regiment. Despite their best efforts to remain a secret society, by late 1865 the IRB had become such a large and popular movement that they were brought to the attention of British authorities. The government carried out a number of raids, seized records and gathered evidence from informers, as a consequence of which many Fenians were arrested, including O’Reilly.

He was sentenced to twenty years’ penal servitude. In July 1866, while awaiting the announcement of his sentence in Mountjoy Prison, he had scratched on his cell wall with a nail: ‘Once an Irish soldier, now an English felon and proud of the exchange’. In 1868 O’Reilly found himself on the Hougoumont. Of the 280 convicts aboard, 62 were Fenians. In order to pass the time as they journeyed towards Western Australia, a group of eight Fenians (including O’Reilly) created a handwritten newspaper, The Wild Goose. The title alludes to the flight of Jacobite soldiers from Ireland in the 1690s. The journal contained articles, poems, satirical pieces and occasional political commentary. The group produced seven editions. At the completion of each, it was read aloud and apparently provided a real morale boost for all concerned. According to historian Ian Kenneally, the ship’s captain was so pleased with its effect that he provided extra rations for the convicts involved in the paper’s production.

ESCAPE FROM FREMANTLE

The Hougoumont arrived in Fremantle on 10 January 1868. Fremantle in Western Australia was the most isolated settlement in the world; as such, it was a reasonable assumption that, once there, prisoners would never be heard of again. It is little wonder, therefore, that many convicts initially dreamed of escape, but prisoners were warned upon arrival that there were only two ways of escaping: ‘through the most cruel country God ever turned over to the devil, a country of deserts, salt-lakes … red hot rocks, poisonous insects and death-dealing snakes’, or through waters containing vicious sharks and where no ship’s master would be prepared to conceal convicts on board.

During 1868 O’Reilly developed a close relationship with the local Catholic priest, Father Patrick McCabe, who offered to help the Irishman escape. McCabe came to an arrangement with the captain of the American whaler Gazelle, who agreed to take O’Reilly on board. Following an eventful journey, nine months after his escape from Fremantle John Boyle O’Reilly arrived in Philadelphia on 22 November 1869. He was the first convict to escape the natural jail that was Western Australia.

THE PILOT

It was not long before O’Reilly achieved celebrity status. He was welcomed by American Fenians as a fugitive hero in the ‘Land of the Free’. He promptly became an American citizen and decided to settle in Boston and work as a journalist. In spring 1870 Patrick Donahoe, the owner of the Boston newspaper The Pilot, offered him a job. This newspaper had been published in Boston for over 40 years in various iterations and is still published today. It began as The Jesuit, then became the United States Catholic Intelligencer and then the Literary and Catholic Sentinel. Its slogan was ‘Be just and fear not. Let all the ends thou aimest at be thy God’s, thy Country’s and Truth’s.’ Throughout its early years it guided an immigrant readership by presenting religious and political matters and by providing opportunity for debate. It also entertained with poems, short stories and satirical pieces. The Pilot kept new Irish arrivals informed about life back home by presenting columns on births, deaths and marriages, and it became the vehicle for finding missing loved ones through its ‘Information Wanted’ advertisements.

Throughout his life O’Reilly advocated for independence for Ireland. As time wore on, however, he favoured constitutional reform rather than physical force, although he never repudiated the ideals of Fenianism. In rejecting militancy, he turned to achieving Ireland’s independence by raising the status and self-esteem of its people. He retained a strong commitment to Ireland, working closely with Michael Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell.

By 1876 he was editor and part-owner of The Pilot. He wrote prolifically and gave many lectures and speeches. Perhaps not surprisingly, The Pilot became one of the most-read newspapers in the country and O’Reilly established himself as a major force in American journalism. As he was so eloquently to state: ‘Ours is the newest and greatest of the professions, involving wider work and heavier responsibilities than any other. For all time to come, the freedom and purity of the press are the test of national virtue and independence.’

THE CATALPA RESCUE

This ideology drove his role in what became known as the Catalpa rescue and in the way he reported it to the American people and ultimately to the world.

In 1873 there were still eight life-sentenced Fenians in Fremantle jail, including James Wilson. Famously, Wilson wrote a letter and managed to have it smuggled to John Devoy in New York. In it he described his as ‘a voice from the tomb. For is not [Fremantle jail] a living tomb? … We think that if you forsake us then we are friendless indeed.’ Devoy’s sharing of Wilson’s letter marked the beginning of a very successful rescue fund. The big question now was how would the rescue be carried out and by whom? Devoy sought counsel from his old friend John Boyle O’Reilly. Both men agreed that the only method with any likelihood of success involved stealth, not violence—sailing a whaler to Western Australia and orchestrating a carefully devised plan.

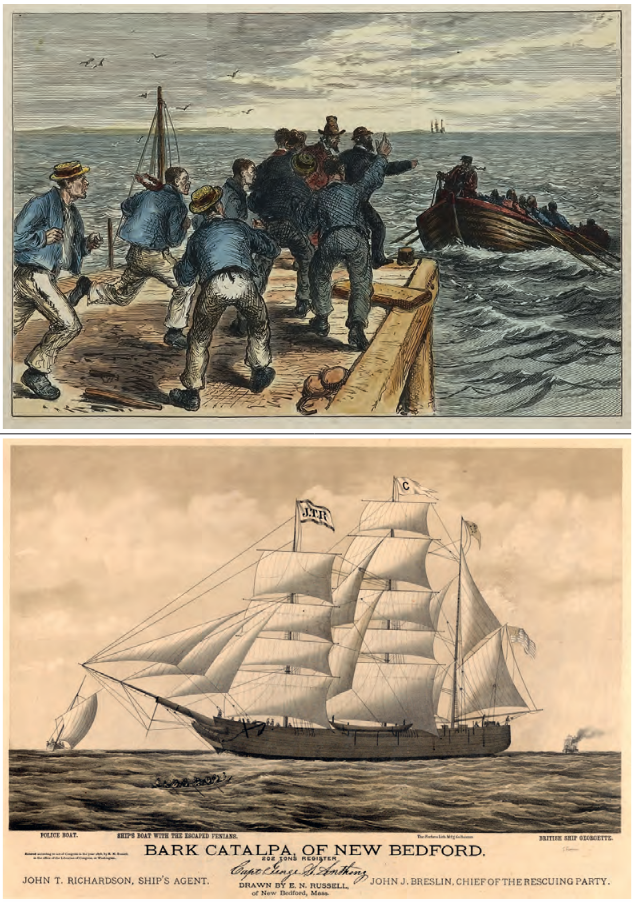

So the Catalpa was purchased, and experienced American seaman George Anthony agreed to captain the ship, which sailed from Massachusetts on 29 April 1875. The operation would require men on the ground—John Breslin and Thomas Desmond, who arrived in Fremantle on 16 November 1875. The Catalpa arrived in Bunbury Harbour, near Fremantle, on 27 March 1876. Following various delays, contact was made with the Fenian prisoners capable of making the break. It took place on 17 April, Easter Monday. Just before dawn, the telegraph wires between Fremantle and Bunbury and between Fremantle and Perth were cut. In other words, Fremantle was cut off from the outside world. Breslin and Desmond met the six prisoners outside the jail in horse-traps and drove frantically to Rockingham Beach, where Captain Anthony was waiting for them with one of the Catalpa’s whale boats.

That afternoon, police cutters from Fremantle and Bunbury sought the escapees, and the governor despatched the steamer Georgette with a contingent of the colony’s Pensioner Guard. Unable to reach the Catalpa, the Fenians and their rescuers spent a miserable night at sea in the open whale boat. The following morning, however, they managed to reach the ship and board it. But the authorities were determined to recapture the Irish rebels. The Catalpa was sighted by her pursuers, who soon drew alongside. When threatened that his masts would be blown in, the American captain pointed to the flag flying behind the ship, declaring: ‘That’s the American flag. I am on the high seas and my flag protects me. If you fire on this ship you fire on the American flag.’

The colonial police were loath to engage in an incident outside territorial waters, so the Georgette was forced to return to Fremantle. Much to the anger and humiliation of Governor Robinson and the establishment in Fremantle, the Catalpa sailed to New York and then to New Bedford. Everywhere the local Irish community gave the Fenians a tumultuous welcome. News of the Catalpa’s success was quickly cabled to John Boyle O’Reilly. On the front page of The Pilot he wrote:

‘There has never been an enterprise so large and so terribly dangerous carried out more admirably. It will be remembered of Irish patriots that they never forget their suffering brothers … the PRINCIPLE was at stake.’

In a private letter to his friend John Devoy he added that ‘This … will do more good for Ireland than a whole unsuccessful attempt at rebellion’.

LATER CAREER

During the 1870s and 1880s John Boyle O’Reilly was one of the most famous journalists and writers in the United States. Between 1873 and 1888 he published a novel set in Western Australia and three collections of poetry, most of it offering commentary on social justice. His work was extremely popular and commercially successful, and he was often invited to give speeches or commissioned to write poems for important commemorative occasions. The issues that he had written and spoken about in relation to Ireland and Fenian imprisonment extended to include the treatment of First Nations and African Americans, as well as the exploitation of the working class by the wealthy. This would continue to find expression in his writing.

O’Reilly’s fiction, like his journalism and other non-fiction, was designed to expose the hypocrisy of the powerful and to illustrate his belief that the divisions in humanity engendered by imperialism, race, creed and money were unjust. He took it upon himself to deliver this message through the written word. Yet this led to anger, frustration and disillusionment, as seen in his lengthy poem ‘From the Earth a Cry’ (1881), in which the planet calls on its oppressed classes to rise:

‘… to be high as the highest that rules them,

To own the earth in their lifetime and hand it down to their children!’

In his later years, O’Reilly was heavily involved in Irish affairs in both the United States and Ireland. He was the centre of a dynamic Irish-American community and continued to be a powerful force in American journalism until his death in 1890.

O’Reilly has been described as one of the Wild Geese, one of the many thousands who fought and worked for Ireland’s independence from a foreign base. He is also credited with changing the perceptions of Irish immigrants. His escape from Western Australia and the role he subsequently played in the Catalpa rescue created headlines around the world and drew attention to his writing in The Pilot. His actions and writing came to symbolise the resilience of the Fenian movement and the power of solidarity across borders.

Angeline O’Neill was Head of English at the University of Notre Dame Australia (UNDA) for twenty years.

Further reading

A.G. Evans, Fanatic heart: a life of John Boyle O’Reilly (Nedlands, 1997).

P. FitzSimons, The Catalpa rescue: the gripping story of the most dramatic and successful prison break in Australian history (Sydney, 2019).

T. Kenneally, The great shame (London, 1998).

P. Vronsky, From rebels to revolutionaries: a brief history of the founding of the Fenians and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (https://fenians.org/fenianbrotherhood.htm).