Harman Murtagh

CAUSES

The British Factor

The war occurred as a result of the fusion of a number of interrelated factors – British, European and Irish. The British factor was the attempt by King James II to use Ireland as a stepping stone to recover the throne he had lost to William of Orange, in the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688. The domestic cause of James’s deposition stemmed from his failure to confine his use of power within limits that were acceptable to the political majority – the conservative Anglican (Church of England) country gentry who formed the Tory party.

The Tories were natural supporters of the monarchy and the parliament of 1685 voted James enough revenue for life to support peacetime government. But the new king was not prepared to leave it at that. A late convert to Roman Catholicism, he felt impelled to fulfil the mission for which God, he believed, had preserved him: the conversion of Protestant England to Catholicism. He thought that this would occur naturally, if people’s religion was left to their consciences by the removal of legal barriers. There was no hope of this policy winning approval with the Tory gentry. English Roman Catholics were a small and suspect minority, so James took the extraordinary step of turning for support to the Dissenters (Presbyterians). They, too, stood to gain by repeal of penal laws, but their opposition to Popery was even more pronounced than that of the Anglicans; they were also allies of the Whigs, the political group which sought the subordination of the monarchy to parliament and which had earlier tried to exclude James from the throne on account of his religion.

James’s high-handed efforts to increase the electoral influence of these unnatural and unreliable allies brought him into conflict with the Tories. Their alienation was completed by their exclusion from government; by James’s vindictive treatment of the Church of England; by his close relations with the absolutist Louis XIV whom they suspected he sought to imitate; by their suspicion of his motives in expanding the army; and by his tolerance of the pro-Catholic policies of his Irish viceroy, Tyrconnell, which many thought a blueprint of his plans for England. James might even have survived these follies were it not for the birth in 1688 of his son, who would secure a Catholic succession, and the invasion of England by William of Orange.

The European Factor

The dominant factor in Europe was the France of Louis XIV. It was the strongest power; prosperous, populous, and relatively united under firm and efficient central government. Louis regarded Spain, though an ailing power, as France’s main enemy because of its control of the Spanish Netherlands, the strategic buffer-zone between France and Holland. He disliked the Dutch as successful rebels and bourgeois Protestants, whose great commercial prosperity he resented. His most inveterate opponent was William of Orange, who had led Holland through the terrible French war of the 1670s, and thereafter dedicated his considerable abilities to thwarting the ambitions of the French king at every turn. William promoted a grand alliance of states against Louis, which eventually included Holland, Sweden, Spain, Savoy, the Hapsburg Emperor and many of the German princes. As international tension mounted, there was intense anxiety in Holland about the position of England under James, whom the Dutch suspected of favouring France. A renewal of the brief Anglo-French alliance of the early 1670s was a recurrent Dutch nightmare. Instead they hoped to secure England’s formidable support for the grand alliance against Louis. William’s invasion of England in 1688 was, therefore, a pre-emptive strike.

William was James’s nephew and closest legitimate male relative; his wife, Mary, was James’s eldest daughter and heir-apparent. If she succeeded her father, there were expectations that England would join the alliance against France, expectations upset by the birth of the Prince of Wales in 1688. William feared that the spectre of a Catholic succession might provoke revolt and a second English republic. The first republic in the 1650s (under Cromwell), had been a commercial and military opponent of the Dutch. If there was to be a move against James, William judged it better to place himself at its head. Although his public declaration made much of his concern for Englishmen’s rights, he was not really interested in England except as a necessary ally in his vendetta against France. Sailing late in the season, with 18,000 troops aboard 250 ships, William landed at Brixham on 5 November 1688.

The English army, undermined by a Williamite conspiracy, offered no resistance. James’s nerve collapsed, and he fled to France, preceded by the queen and the infant Prince of Wales. William summoned a ‘convention parliament’ which declared that James had abdicated by deserting his people and breaking the laws. The convention offered the throne jointly to William and Mary, who accepted. Grudging Tory acquiescence in these very novel constitutional arrangements was secured by playing on fears that the alternative was anarchy. A similar convention in Edinburgh gave William and Mary the throne of Scotland.

The Irish Factor

Alone of James’s three kingdoms, Ireland had a majority of his Roman Catholic co-religionists, consisting of about three-quarters of the population, comprised of the earlier inhabitants of the island of both Gaelic and Norman (‘Old English’) descent. The preceding century had weakened their position in almost every respect as they lost ground to the newer English and Scottish Protestant settlers, introduced by the plantations. They comprised the remaining quarter of the population and were most heavily concentrated in Ulster.

Relations between the two groups were tense. Despite its losses, Irish Catholic civilisation, fortified by the Counter-Reformation, retained a good deal of underlying strength. James’s accession improved their position and revived their hopes. The Earl of Tyrconnell, their leading spokesman, became Viceroy. Catholics soon took over the Irish army, and were brought into the judiciary and other public offices. Simultaneously the ground was prepared for a Catholic majority in parliament to achieve Tyrconnell’s political objective – the repeal of the Restoration land settlement. Protestants in Ireland felt threatened by this policy and for the most part they welcomed James’s downfall. The Glorious Revolution was a severe blow to Tyrconnell and threatened his hopes for the revival of the Irish Catholic community. Under Irish law, whoever was king of England was also king of Ireland and William indeed had accepted the Irish as well as the English throne from the convention parliament.

French Involvement

Louis XIV gave the exiled James a warm welcome. William’s seizure of England had been a major and unexpected setback to French plans. James’s restoration would clearly be in Louis’s interest; even its attempt was worthwhile, provided it was not too costly on French resources. It would destabilise the British Isles sufficiently to distract William and divert his resources from the Continent. Over the next three years, eight major French convoys sailed to Ireland, carrying large quantities of arms, ammunition, money, military supplies of all sorts, French generals and officers, returning Jacobite exiles, and 6,500 French troops for the 1690 campaign. Without French encouragement, it is quite possible that Tyrconnell would in the end have stoically accepted the Glorious Revolution; certainly, without Louis’s material support, the Irish Jacobite army could never have sustained its remarkable three-year campaign in Ireland.

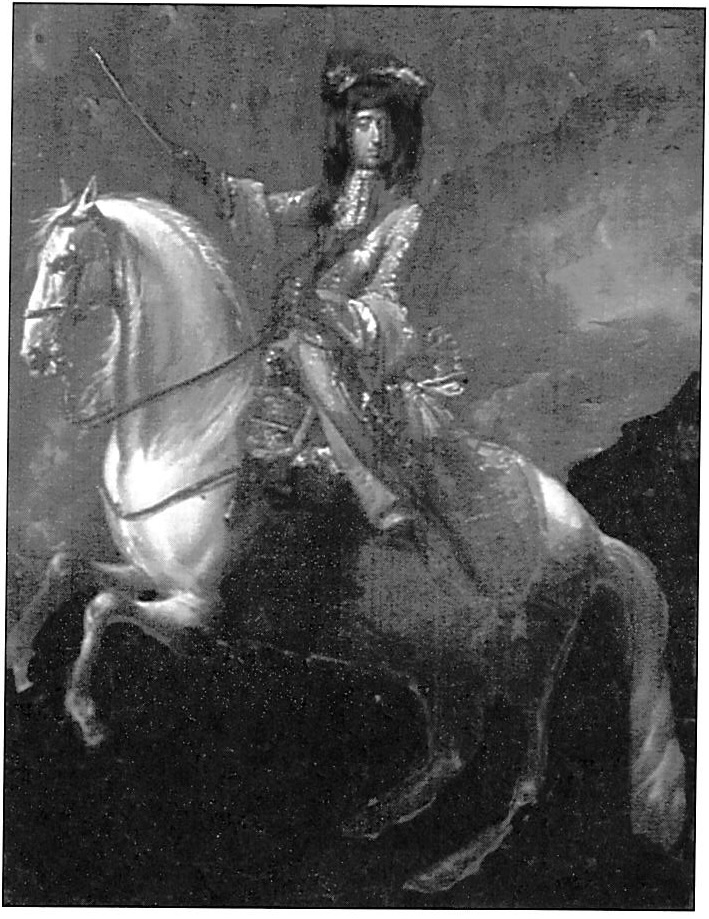

Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) –

City of Manchester Art Gallery

James’s Plans

The Glorious Revolution had been a shattering blow to James’s self-confidence and he viewed the prospect of renewing the contest with William – especially in Ireland – without enthusiasm. He reluctantly sailed to Ireland to lead the bid for his restoration in person. His presence gave the Irish resistance to William a legitimacy that the leading Jacobites’ fathers had lacked a generation earlier in the Confederation of Kilkenny; but it was irksome to James that, as the price of Irish support, he was obliged to agree to the immediate summoning of a Catholic-dominated parliament in Dublin at which the leading Irish Williamites were attainted and the Restoration land settlement reversed. William had already announced that he would forfeit the lands of his opponents.

Louis’s intervention on behalf of James focused William’s attention on Ireland as nothing else would have done. And it had the immediate major benefit for him of overcoming English opposition to joining the alliance against Louis, so that in May 1689 England at last declared war on France. Parliament also granted funds towards the reduction of Ireland which belatedly enabled William to relieve the beleaguered Protestants in Derry.

Thus, the three factors – European, British and the Irish – all fell together, to involve Ireland as an important theatre in a major European conflict, which was at the same time a British dynastic dispute and an Irish civil war. William’s personal intervention was required in 1690 and victory for his army was only finally secured in 1691 when the Treaty of Limerick, brought the war in Ireland to a conclusion. The wider European war ended in stalemate with the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697.

CONSEQUENCES

For James

It finished King James. At Ryswick, even Louis reluctantly recognised William as king of Great Britain, although he refused to repudiate James’s claims, and declined to expel James from France. The Jacobite court at St Germain continued to be a centre of intrigue against William, but the exiles were poor and demoralised; there was much division and, in reality, they were increasingly a very marginal factor in English politics.

For William

For William, victory in Ireland consolidated his seizure of the British Isles from James and saw off the threat of direct French intervention in one of his kingdoms which was intended as a springboard to the others. His goal of denying Britain as an ally to Louis was achieved, and the French intervention in Ireland resolved the related problem of bringing England and her resources into the grand alliance against France. England contributed the lion’s share of the alliance’s naval resources, a substantial number of troops and a good proportion of its financial needs.

For Louis

Outwardly, the French intervention in Ireland had not been a success for King Louis. He had not, after all, succeeded in restoring James or ousting William. But the real motive of the French was to destabilise the British Isles and thereby divert William from the Continent. And in this the Irish adventure was highly successful for the French. The cost was comparatively light; certainly it was only a fraction of the cost to William of containing it. In 1690, for example, the only year that Louis sent troops, his commitment was about one fifth of the number William brought in from outside. And at the end Louis received a handsome dividend of trained Irish soldiers to support his war-effort on the Continent. Thus, the war in Ireland cannot really be regarded as a defeat for French policy. Throughout the Irish war, the French navy sailed the high seas with impunity, a foretaste of the coming French interest in expansion overseas that was to reach its apogée under Louis’s successors, although James’s defeat ensured that Ireland remained outside the French colonial and commercial hegemony.

For Irish Protestants

For Irish Protestants, who had supported William, the war was a great success. With the crushing of their opponents, their ascendancy was assured for the next hundred years, and the ‘protestant nation’ was born. Throughout the eighteenth century, it monopolised parliament, government, the public service, the army, the church, the higher echelons of the law, higher education and land ownership. However, the Anglicans proved rather ungenerous in victory to the Dissenters (Presbyterians) who continued to suffer from legal disabilities and economic deprivation. In general, too, Protestants resented the concessions made to the Jacobites to secure peace which they viewed at the time as a profligate disregard of their best interests. They also paid a substantial price in terms of the considerable physical and economic damage wrought by the war.

The Glorious Revolution increased the importance of the Irish, as well as the English, parliament. Overwhelmingly Anglican in membership thereafter, and still smarting from the wartime experience, it enacted a series of anti-Catholic penal laws in the 1690s and early 1700s. To secure Anglican ascendancy, the Penal Laws also affected Dissenters. The main practical impact of this draconian body of legislation was to consolidate and perpetuate the de facto post-war status quo by excluding Roman Catholics from public and professional life and making it difficult for them to own or rent land.

For Irish Catholics

Along with King James, Catholics were the real losers of the war. Although the articles of Limerick and Galway gave them some protection, the immediate impact was a fall in their share of land ownership from 22 to 14 per cent; and the proportion diminished further in the eighteenth century to about 5% by 1780. In fact, the severity of their defeat broke for ever the Catholic gentry as a group of political, economic or military significance in Irish life. The Catholic revival initiated by Tyrconnell was now dead, and the underlying forces that had provided its vitality were spent. When Irish radicalism began to gather momentum, in the wake of the American and French revolutions, the remnants of this group were only a minor part of the movement. This sharp, indeed terminal, decline in fortunes was mainly experienced by the land-owning elite, but the Catholic tenantry who had followed the old gentry loyally throughout the war, and suffered with them, would surely have preferred them to the new.

Instead, the ablest and most enterprising representatives of Catholic Ireland were to be found on mainland Europe as churchmen, businessmen and above all as soldiers. The war resulted in the exodus of 20,000 Jacobite veterans to the Continent to serve the Catholic states of France, Spain, Naples and the Habsburg empire. The tradition endured, and the process of emigration to the Continent, especially military emigration, continued throughout much of the eighteenth century.

Harman Murtagh lectures in law at the Regional Technical College, Athlone.