By Ruairí Nolan

The first and still one of the most comprehensive of the biographies of Lord Edward Fitzgerald is that by Thomas Moore from 1831. It utilises a plethora of correspondence to fill in the contextual gaps of his narrative, giving us a great insight into the life of a man constantly at odds with the world he finds himself inhabiting. We do, however, encounter issues with Moore’s writing in that, like R.R. Madden, he at times heavily edited what was included. Nevertheless, what is wonderful is that we have access to all of the original letters used in his biography—acquired, after being thought lost, by the National Library of Ireland in 1999. Thus we have access to the original handwritten correspondence of the rebel aristocrat during his time on the North American frontier, and he paints a truly marvellous picture of his time there, while also raising questions about the impact of his experience on his political sensibilities.

ORIGIN OF HIS REPUBLICAN IDEALS?

Daniel Gahan has previously explored the extent to which Fitzgerald’s experience changed his political outlook; his daughter Pamela later claimed that ‘my father had got his republican ideas in America’. Fitzgerald travelled there twice—first as an eighteen-year-old officer in the British army, fighting in the American War of Independence, and later in 1788–9, stationed in New Brunswick and then travelling, rather circuitously, to New Orleans as a civilian. Pamela never quite specified in which instance he formed his views, but considering that he remained a stalwart officer in the army until c. 1789–91—his letters are peppered with references to a future conflict with the newly formed United States—we might assume that she meant his journey through the frontier of the newly formed United States and Canadian territories.

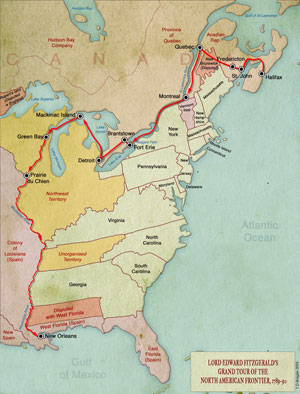

Utilising Gahan’s work, Lord Edward’s correspondence and an accompanying map from Moore’s 1831 biography, we can piece together a rough arrangement of Fitzgerald’s tour. He was stationed in New Brunswick with command of a regiment; when the winter of 1788 set in and training became impossible, he set about keeping busy by going on hunting trips, skating on the frozen lakes and rivers, and finally embarking on a walk, by snowshoe, to Quebec. What stunned contemporaries was the route that he and his companions decided to take: rather than following the rivers (then the main thoroughfares of the region), which covered a total of 350 miles, they elected to take a straight line, covering a distance of 175 miles, relying on their compass alone. Fitzgerald himself noted in a letter dated 2 February 1789, prior to his departure, that ‘our route will be quite a new one and has not yet been gone by anybody except Indians’. Their trek brought them to within a league of Quebec City on 13 March 1789.

After a couple of weeks, Fitzgerald made his way down the St Lawrence Valley to Montreal in the final days of April. From there he took a schooner across Lake Ontario to see the Niagara Falls. It is at this point that he appears to have been almost swept away in the wanderlust of it all. When writing to his mother from Fort Erie on 1 June, he says: ‘I am just come from the Falls of Niagara. To describe them is impossible … Homer could not in writing, nor Claude Lorraine in painting.’ Later in this same letter he laments that ‘I think of you all often in these wild woods, they are better than rooms. Ireland and England will be too little for me when I go home.’ In Montreal or Fort Erie he fell in with Joseph Brant, a Native American chief familiar with the politics of the Old World, having visited London twice. Fitzgerald travelled by canoe when crossing stretches of water from this point on. After the boat trip across Lake Ontario he was ‘as sick as at sea—so you may guess I prefer canoeing’.

MADE AN HONORARY CHIEF OF THE SENECA/BEAR TRIBE

They made their way through southern Ontario, travelling up the Grand River as far as Brantstown (Brantford today) before heading west to the River Thames and onward to Detroit. Fitzgerald’s letter from here on 20 June to his mother is short and sweet, talking of the unbearable heat: ‘it is so hot I can hardly hold the pen … really it is too hot for anything but lying on a mat’. We get a better idea of his experiences among the Native American tribes at this juncture, as he speaks of developing a close relationship with Joseph Brant and spending quite a bit of time among the Native American communities along the way. He writes: ‘My friend Joseph always travels with company; and we shall go through a number of Indian villages. If you only stop an hour, they have a dance for you.’

The only other Native American whom he named was David Hill, chief of the Iroquois. It was through Hill that Fitzgerald became a ‘thorough Indian’, being formally inducted into the Seneca/Bear tribe and made an honorary chief at Mackinac Island. The resulting document was a treasured part of Fitzgerald’s personal papers for the remainder of his life, but sadly it has since been lost.

From this point in his journey large assumptions must be made about the specific direction he took. From Detroit we have a rough outline of where he went. He tells us that the next stop was Mackinac Island at the confluence of Lakes Huron and Michigan. There are no more letters between here and his arrival at New Orleans, which by his own estimate was half of the entire journey.

NEW ORLEANS

Once he arrived in New Orleans, in December 1789, he wrote two letters to his brother Robert in Spain, one in Spanish and the other in English; Thomas Moore has thankfully provided a translation in his biography. It was while there that he learned that the woman he had hoped to court back home, Georgiana Lennox, had married earlier in the year—the reason, perhaps, that prompted an urge to travel in the first place. He embraces the news like a stoic in his first letter: ‘I think no more about them, as my happy temperament does not allow me to dwell for any length of time on things which are disagreeable’.

His mood here is certainly low, and we can see an inner turmoil—a desire to return to his family but similarly to continue travelling. He talks of his eagerness to be home the following spring, yet in the follow-up letter, days later, he speaks of his desire to visit Mexico or Havana, but the Spanish governor won’t let him in. It seems that he wished to remain abroad a bit longer, perhaps a consequence of his bad news. It is in his second letter—the final one to be written from America—that he speaks openly of his time travelling and how it has greatly changed him: ‘it has done me a great deal of good. I have seen human nature under almost all its forms. Everywhere it is the same but the wilder it is, the more virtuous.’ This last point is interesting, in that the only detailed accounts he provides of ‘wild’ human nature are from the territories of New Brunswick, the St Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes. From the Great Lakes to New Orleans we hear of no interactions or encounters with settlers or native peoples, although he surely would have encountered much more remote and, by his own estimate, ‘wild’ communities. In spite of this we are told nothing of their ‘virtuous’ ways.

THE ‘NOBLE SAVAGE’

So, returning to Pamela’s words, did he get his ideas in America? One must consider the upbringing he received; Moore would have us believe that he picked it all up in America, but it would appear that Lord Edward embarked with many of the same ideas and assumptions with which he returned. This is reflective of his upbringing in an education and household steeped in the teachings of Rousseau and the idea of the ‘noble savage’.

This romanticised view of native society can be seen in Fitzgerald’s lack of interest in discussing natives beyond early entries while in New Brunswick with the likes of David Hill and Joseph Brant. He likely would have encountered more isolated native and settler communities further along on his journey as he passed the Great Lakes and on to the Mississippi—but of these he wrote nothing. Despite saying that the ‘wilder it [human nature] is, the more virtuous’, he seemed reluctant to embrace much of native society beyond Montreal and the Great Lakes, where his dinners with Joseph Brant would probably have been very aristocratic affairs, with enslaved Africans as servants.

Fitzgerald is remembered as one of the most romantic figures of the 1798 Rebellion—the lord who went to Paris and renounced his titles amidst the revolutionary fervour. With access to his letters, we are presented with an opportunity to delve into the mind of this great historical figure, to understand how he came to believe what he did.

Ruairí Nolan is a library assistant in the National Library of Ireland.

Further reading

D. Gahan, ‘“Journey after my own heart”: Lord Edward FitzGerald in America, 1788–90’, New Hibernia Review 8 (2) (2004), 84–105.

Letters from a book of correspondence as part of the Lennox, Fitzgerald and Campbell Papers, MS 35,011, National Library of Ireland.

T. Moore, The life and death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald (London, 1831).

S. Tillyard, Citizen lord (London, 1997).