By Donal Fallon

As far as Irish civic museum spaces go, Galway’s is particularly busy. Active within the cultural life of a city more synonymous with the arts and heritage than any other on the island, its exhibitions in 2023 included the wonderfully titled The West is Awake (from one West Coast to Another), exploring 50 years of hip-hop culture through the lens of an Irish photographer who captured such hip-hop luminaries as Notorious BIG on film. That was part of the Galway International Arts Festival. The museum is the kind of place that encourages repeat visits. Strong local interest ensured that This is the Modern World, originally intended to run throughout the summer of 2023, continued into this year. Those who like things a little bit more traditional will find it here too, with permanent exhibitions dedicated to local themes like the Claddagh and the writer Pádraic Ó Conaire.

In recent years, much work has been done on exploring youth culture and musical subcultures in the capital, including Garry O’Neill’s excellent Where Were You: Dublin Youth Culture & Street Style, 1950–2000. A successful exercise in crowd-sourcing, that book and online community served as an archive of teenage memory and a people’s history that quickly flew off the shelves. Then came Throwaway: Dublin Club Flyers 1990–1999, a beautifully designed collection of flyers that document the changing landscape of Dublin nightlife culture, including legendary venues and nights like the Hirschfeld Centre, the Temple of Sound and Sides.

While Dublin was a frequent place of pilgrimage for young music fans from right across the island, all Irish cities maintained their own active local ‘scenes’, as this wonderful exhibition at Galway City Museum reminds us. Listeners to RTÉ’s ‘Documentary on One’ last August, Louder than Bombs: The Smiths in Ireland, Nov 84, will be familiar with the ‘circuit’ on which bands who ventured beyond Dublin found themselves embarking. If the SFX and the National Stadium were the defining venues for Dublin, Galway became synonymous with the unlikely setting of Leisureland.

This is the Modern World focuses on a period of five years, from 1977 to 1982, when the Irish music scene was in a moment of flux. Some of this reflected international changes in musical taste and genres, with the emergence of punk rock in Britain. Though purists look to New York City and not London as the birthplace of the genre, the commercial explosion of acts like The Sex Pistols and The Clash in the UK had significant impacts here. Other manifestations in the same period were more local, with the continued success of acts that fused traditional Irish music with other genres, such as Moving Hearts and Horslips. The title, surprisingly enough, comes not from a local band but from The Jam’s second album.

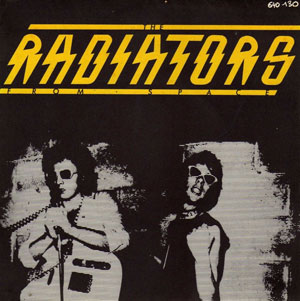

Cleverly, this exhibition avails of technology by including a curated Spotify playlist of featured artists. The visitor is encouraged to scan a code, which brings you to a one-hour musical journey that provides music from significant international acts like The Jam and Dexy’s Midnight Runners who visited the city, but also includes important Irish acts like The Radiators From Space. This far-reaching, diverse playlist captures the musical richness of these five years. The use of Spotify in a museum setting is certainly unusual in an Irish context but has become increasingly common in culturally focused exhibitions elsewhere. Without setting foot in the museum, listeners can enjoy the Boston Museum of Fine Arts playlist that accompanied their exhibition Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, while New York’s Museum of Modern Art first utilised a Spotify playlist alongside an exhibition in 2015.

In notes accompanying the exhibition, Tom Prendergast of Buzz Promotions in Galway recalled the process of postering for gigs like these. It’s a recollection that others—political activists, perhaps—will likewise remember:

‘It’s two in the morning—a relatively safe hour to take to the streets. Posters under one arm, bucket, paste and brush in the other. Streets, poles, and billboards already selected, so off I set, on foot.’

Crucially, in a time before online forums and with the State effectively cracking down on pirate radio stations at that time, the humble poster was vitally important.

Any exhibition of concert posters is ultimately as much about the designers as the musical acts. Internationally, the period witnessed a number of artists coming to prominence through their strong working relationships with musical acts, such as the recently deceased Jamie Reid, the designer of much of the imagery of The Sex Pistols. At home, the most significant figure in the field was Steve Averill, then known as Steve Rapid, of The Radiators From Space. Averill was also responsible for the aesthetic direction of the early U2, a name he himself suggested for the group formerly known as The Hype. He has recalled in an interview how ‘I also knew that, graphically speaking, a single letter and a single numeral together would look very strong on a poster—it would be very identifiable’. Alongside Averill’s logos we also encounter a poster for Thin Lizzy, whose close working relationship with the artist Jim Fitzpatrick produced a distinctive and immediately recognisable aesthetic for the band.

Other approaches to an exhibition like this are possible, including oral history. Some concerts from this period, particularly in Dublin and Belfast, have been well documented. Bono recalled The Clash at Trinity College, Dublin, as being a defining moment in his own life—not so much a concert and ‘more like the Red Army had arrived, on a cold October night, to force-feed a new cultural revolution, punk rock’. Dave Fanning, on the other hand, insists that ‘it was awful. But you weren’t allowed to not like it. So everyone said they loved it.’ Some nights, like The Clash playing Trinity’s eighteenth-century Examination Hall, have even inspired academic conferences. Such accounts of concerts outside Dublin and Belfast are much rarer but could still be gathered. Indeed, exhibitions like this one provide an inspiration to actively seek them out.

Donal Fallon is the presenter of the Three Castles Burning podcast and author of Three castles burning: a history of Dublin in twelve streets (New Island Books, 2022).