By Seán Whitney

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, in a letter from Armagh in 1769 warned his followers not to take snuff, and noted that the Irish were like ‘no other nation in Europe in such vile bondage to this silly, nasty, dirty custom’. Whether it was in the form of snuff or pipe tobacco, Irish people, and especially the poor, were enthusiastic consumers of the ‘fragrant weed’. Despite its presence in Ireland since Elizabethan times, tobacco—unlike its excised cousins in brewing and distilling—has not attracted much academic interest. While economic historians have referenced it in terms of imports and duties raised, little of its significant contribution to the economic and social life of the country has been examined. Recent research has shown that the manufacture, retailing and occasional domestic cultivation of tobacco gave rise to an industry that catered for an increasing level of consumption, creating healthy profits for the trade and becoming a valuable source of revenue for the state.

PROTO-INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION

The industry developed from one of horseback pedlars in the seventeenth century, such as the fictional Roibin an Tabac in the seventeenth-century satire Pairlement Chloinne Tomáis, to one that could, in the early decades of the twentieth century, boast of Gallaher’s in Belfast as being the largest privately owned tobacco firm in the world. In between, the industry comprised local grocers and small manufactories employing a handful of workers who supplied a proprietary product for local consumption. By the 1830s there were up to 290 such establishments in Ireland supplying 12,000 retailers, whereas in Britain the corresponding figures showed 380 manufacturers catering to 159,000 licensed dealers. The 1841 census informs us that 1,100 were engaged in manufacture, which confirms the small nature of most of the businesses. Factory inspectors’ reports up to the 1880s describe many of the premises as being unsuitable in scale and condition for tobacco production. Those reports and commissions on the employment of children paint a dispiriting picture of how child workers were treated. Coming from the most impoverished areas, the physical stature and well-being of the child workers, some as young as five years old, were poor, as was their level of education and religious instruction. Set to work on monotonous tasks, which one inspector noted ‘could be performed by well-trained dogs or monkeys’, they worked each day except Sunday and enjoyed a day’s holiday at Christmas and Easter. Business-owners often subcontracted the work to an adult spinner or twister who hired the children and paid their parents directly. Those workers who did not advance to the position of spinner became too expensive to hire at adult wages and were dismissed from a trade whose limited skills were not transferable. Resulting from such a prospect, many of the teenage workers were noted by factory inspectors to have a ‘come-day go-day’ attitude to their employment. By 1843 the number of these local businesses had decreased to 210, which illustrates the speed at which inefficient businesses were forced from the industry.

TOM ‘THE TOBACCO KING’ GALLAHER

From the 1880s the more progressive firms embraced modern methods to run their businesses by investing in power-driven machinery to cut, press and package tobacco and astutely reinvesting profits in ever-increasing amounts in the advertising and marketing of their branded products. Chief among these progressive firms was Gallaher’s of Belfast, which can lay claim to be the first truly multinational Irish firm.

Tom Gallaher, who began his business in Derry in 1857 selling tobacco from a barrow, established factories in the 1880s in Belfast and London and later secured his source of raw material by purchasing tobacco farms and rehandling stations in Kentucky. In 1887 a factory inspector noted the growth of Gallaher’s business. He wrote that Gallaher was a significant employer, paying an average of £8,000 per week in duty to the revenue, which ‘exceeds considerably’ the total revenue generated in duty by the numerous firms in the area who had gone out of business in recent years. Gallaher developed markets in Britain, across the empire, in Scandinavia and in the USA. His York Street factory in Belfast was greatly extended and modernised at intervals to meet growing demand, and of its roof a journalist wrote that ‘one could easily play a game of cricket or football’ on it.

The working conditions in Gallaher’s were a source of pride to the owner and the now mainly female low-wage workforce, with canteens serving subsidised meals, recreational facilities and company excursions. The introduction of a shorter 48-hour week made employment there a much-desired ambition among the unskilled working class in Belfast. Discipline was strictly enforced in the factory and company records show that employees were dismissed for drunkenness, theft and fighting—and for laughing and singing. One unfortunate worker was dismissed for being ‘stupid’. Gallaher was somewhat exceptional in that he employed workers from across the confessionally divided city, as a nominal survey of the workforce reveals. Despite these liberal tendencies, Gallaher was very much anti-trade union. As chairman of the Belfast Steamship Company, he was embroiled in 1907 in a fight for union recognition by Belfast dock workers led by James Larkin. The dispute affected the tobacco firm when Gallaher dismissed a small number of employees who had attended a rally in support of the strikers. The following day all the workshop employees came out in support of their colleagues, but they returned to work shortly afterwards. The docks dispute continued for three months, with the workers up against strike-breakers, the British army and an intransigent Gallaher.

The unyielding nature of Gallaher’s character was also evident when the entire Irish tobacco industry came under threat from the Imperial Tobacco Company. This was an alliance of British firms formed in 1901 to protect their market from the predatory American Tobacco Company, run by James Duke, in what became known as the ‘tobacco war’. Following the ‘war’, Imperial turned its attention to the Irish market, where the native firms led by Gallaher had refused to amalgamate with Imperial. Unlike many Irish industries in the previous century, the tobacco trade proved to be much more resilient to foreign intrusion. While Imperial had success in the fledgling cigarette market in Ireland, they failed to make inroads in the more popular pipe-tobacco sector, which commentators felt was due to the superior Irish product and loyalty to Irish producers in a period of revived Irish nationalism. Gallaher’s and Dundalk’s P.J. Carroll took the fight to their competitors by launching ‘Park Drive’, Gallaher’s successful response to Imperial’s ‘Woodbine’, while Carroll’s pursued a profitable line in the Scottish pipe-tobacco market. Prior to the Great War, Ireland became a net exporter of manufactured tobacco largely thanks to Gallaher’s, but the entrance of Imperial into the Irish market did enable the latter to get a foothold in the cigarette sector, which would later become the dominant mode of consumption in Ireland.

THE GREAT WAR AND TOBACCO

The Great War was good for the worldwide tobacco industry. General Pershing of the US army gave tobacco a ringing endorsement when he declared that he wanted ‘tobacco as much as bullets … tobacco is as indispensable as the daily ration, we must have tons of it without delay’. Despite attacks on convoys, the fears that the supply of tobacco would be affected never materialised; the provision of valuable space on supply ships stood as testament to its importance to the war effort and to both civilian and military morale. Consumption levels increased owing to the demand from the trenches and from the increasing number of visible women smokers, who, following a day’s labour in formerly male occupations, took comfort in what was also formerly a male preserve. The inclusion of tobacco in British army rations for the first time and the donations organised by volunteer groups also increased demand, and many soldiers who were previously non-smokers took up the habit while serving at the front. The conflict presented both challenges and opportunities for tobacco firms; Murray’s of Belfast lost a considerable number of its male workforce in 1916 to the Royal Irish Rifles, whilst Carroll’s successfully pleaded their case to allow night-time production to fulfil government contracts. The war also changed the mode of consumption; the convenience of cigarettes made them popular with troops in the trenches, and many pipe-smokers continued to use them after the war. By 1921 cigarettes exceeded pipe tobacco in Britain, a milestone reached a decade later in the Irish Free State.

TOBACCO AND THE IRISH FREE STATE

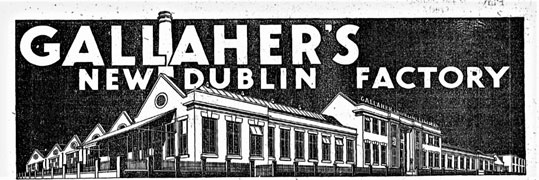

Following the establishment of the Irish Free State, components of the Imperial group—Wills, Player’s and Clarke’s—established tariff-jumping factories in Dublin, while Carroll’s responded similarly by setting up premises in Liverpool and later in Newry. By this stage the number of manufacturers in the Free State was reduced to seventeen, which included some who still operated on a very small scale in the diminishing pipe-tobacco market. Medium-sized firms such as Clune’s of Limerick failed to produce a successful cigarette brand and, suffering from falling pipe-tobacco sales, they developed a wholesale business selling other firms’ products. The closure of Goodbody’s of Dublin in 1929 was a major blow to native industry, as it was once the largest tobacco firm in the Free State. In an enterprising move, its Limerick rivals, Spillane’s, made a serious attempt to stay in business by purchasing Goodbody’s machinery and hiring some of its senior staff. Spillane’s, the owner of the iconic ‘Garryowen Plug’ brand, also facilitated the entry of the British firm Carreras into the Irish market by producing their ‘Craven A’ cigarettes at their Limerick factory.

Ulster firms also headed south. Murray’s in 1925 and later Gallaher’s commenced production at their state-of-the-art East Wall factory in 1929. The resultant increase in employment can be viewed as one of the more successful aspects of the economy in the early years of the state. By 1927 the industry’s output was valued at £5 million. It was also a considerable employer, with over 2,170 employees whose wage bill totalled more than £286,000. The progress in the industry stalled in 1932, when Gallaher’s new factory in Dublin was closed with the loss of 300 jobs. The imposition in the budget of a protectionist duty of an additional 7d. per pound on tobacco produced by companies not operating in the Free State before 1922 and other elements of the Control of Manufacturers Act were deemed by Gallaher’s to be discriminatory. The ensuing political row saw the Labour Party and Cumann na nGaedheal attack the policies of Seán Lemass, who as Fianna Fáil minister for industry and commerce stoutly defended the government’s protectionist position. The gap in the market left by Gallaher’s proved advantageous to Carroll’s, which unsurprisingly endorsed Lemass’s position regarding native industry. Carroll’s profits rose considerably in the following years and, in the opinion of a long-standing employee, state intervention had greatly helped: ‘Dev put Carroll’s on the map … that time was boom times for Carroll’s’. The effective elimination of Gallaher’s from the southern market was accompanied by the opening in 1934 of a factory in Newry to produce the ‘Sweet Afton’ cigarette for the Northern Irish and British markets. In the same year the company offered shares to the public. Benefiting from audited results that showed a steep rise in profits in the early 1930s, applications for shares were heavily over-subscribed and the sale was closed within a few minutes of their release in October 1934. Carroll’s were the last family firm of note in the Irish tobacco trade. In the following years the public company acquired the brands formerly owned by Spillane’s, Murray’s and Ruddell’s.

Political influences in Ulster also affected Gallaher’s after Tom Gallaher’s death in 1927. In 1929 his family sold the business to a London-based investment company. The company continued to grow and this necessitated an expansion in its production capacity. The board of the company favoured expanding its London factory owing to the ‘obvious arguments’ in favour of siting it in Britain, which accounted for 90% of its sales. A major concern for the board was its fear of attacks on its Belfast factory and shipments from Belfast by advanced nationalists. The chairman of the board received assurances from the Stormont government that it would provide ‘every protection’ to enable the firm to carry out its business ‘without loss, interference or embarrassment’, at no cost to the firm, thus indicating the economic importance of the firm to the Northern Irish economy.

The tobacco industry in Ireland in the later decades of the twentieth century comprised three major companies: Gallaher’s, Players (Imperial) and Carroll’s. The increasing evidence linking tobacco consumption and major illnesses resulted in a serious decline in consumption in Ireland and most western countries. The Irish state was among the earliest to introduce severe anti-tobacco legislation, which, alongside increased societal opposition to tobacco, has made the manufacture, sale and consumption of tobacco much more difficult and expensive. In 2017 the now Japanese-owned Gallaher’s closed its factory near Ballymena. Today tobacco is no longer manufactured in Britain or Ireland.

Seán Whitney is a former employee in the tobacco industry and completed a Ph.D in 2019 on ‘The Irish tobacco business 1779–1935’ (available at ulir.ul.ie).

Further reading

A. Bielenberg & D. Johnson, ‘The production and consumption of tobacco in Ireland 1800–1914’, Irish Economic and Social History 25 (1988), 1–21.

J. Goodman, Tobacco in history: cultures of dependence (London, 1993).

M. Hilton, Smoking in British popular culture: perfect pleasures 1800–2000 (Manchester, 2000).