By Cora Crampton

Up to the end of the sixteenth century the Gaelic polity relied heavily on intermarriage as a crucial means of consolidating political and military power bases. To this end, high-status Gaelic women functioned as political resources under the control of their male relatives. It is proposed to examine available traces of the historical imprint of three women of the Gabhal Ragnaill O’Byrne clan to achieve a better understanding of the nature of Gaelic political marriage in the patriarchal and increasingly violent world in which they lived. The three women—Sadhbh O’Byrne, Margaret O’Byrne and Sadhbh Kavanagh—were related to Feagh Mac Hugh O’Byrne (c. 1544–97) as mother, half-sister and wife respectively. This period saw the heavy-handed encroachment of the Tudor state into Gaelic territories, developments that presented serious problems for the O’Byrnes.

SADHBH O’BYRNE

Sadhbh O’Byrne, daughter of Feilim Buidhe McLorcan O’Byrne of Clonmore, was given in marriage to the ambitious Hugh Mac Shane O’Byrne (c. 1520–79) of the Gabhal Ragnaill O’Byrnes around 1543. Sadhbh’s family were clients of the influential Old English family the Butlers of Ormond. Sadhbh is referenced in the Leabhar Branach (the O’Byrnes’ poem-book) by the patronymics inghin Fhéilim Buidhe and inghin Fhéilim—that is, as her father’s daughter but without reference to her own name. This manner of representation adheres to the normal convention for referring to a married woman, which generally only occurred in the iargcomharc or complimentary address at the end of a classical Gaelic poem. Around 1544 Sadhbh and Hugh became the parents of a son, Feagh, and a daughter, Elizabeth.

By 1548 Hugh’s prolonged military conflict with the powerful Butlers concerning territory near Shillelagh eventually cost him the support of his wife’s family. Two years later, Hugh and Sadhbh had divorced. In the increasingly fraught political climate, the Clonmore O’Byrnes may have exerted pressure to force a separation. Even after marriage, a Gaelic wife’s own relatives never fully relinquished all their rights and interests over her. A woman such as Sadhbh was obliged to accept that family ties were more important than marital ties. By August 1550 Hugh, having put away his first wife, had addressed the political imperative of forging a more stable alliance with the O’Tooles of Castlekevin through his marriage to another Sadhbh, this time Sadhbh O’Toole, daughter of Art O’Toole. Following her divorce, Sadhbh O’Byrne’s family brokered her second marriage, this time to the chieftain Diarmuid Dubh Kinsella, obliging her to relocate to north Wexford.

IRISH SECULAR MARRIAGE

At this stage in our study it would seem appropriate to ask how it was possible for Hugh to divorce one wife and marry another while his first wife was still living. The answer lies in the operation of what Kenneth Nicholls terms ‘Irish secular marriage’. Gaelic law rather than canonical law regulated the relationship of most élite Irish couples. Gaelic law allowed divorce-at-will followed by remarriage and ignored the Church’s prohibitions against affinity and consanguinity. Chieftains changed their marital partners to suit their political circumstances and ambitions. It is consistent with the transient nature of Gaelic marriages that a woman retained her father’s name after marriage, and this may also reflect the strong links she continued to maintain with her own family. Anthropologist Levi-Strauss’s assessment of the general nature of negotiated marriages in kinship societies might usefully be applied to Gaelic marriages of this era; such marriages were established ‘not between a man and a woman … but between two groups of men’. Gaelic marriages did not involve the transfer of property, which meant that complications relating to marital assets did not arise upon the termination of Sadhbh O’Byrne’s marriage beyond the repayment of the dowry to her family.

MARGARET O’BYRNE

In 1573 Margaret O’Byrne, a daughter of Hugh Mac Shane O’Byrne’s marriage to Sadhbh O’Toole, was given in marriage to Rory Óg O’More (c. 1544–78). Rory Óg is believed to have been fostered for a time by Hugh at Glenmalure, making this marriage a union between foster-siblings. Rory Óg had already been married to an unknown wife by whom he had four sons. In political terms Rory Óg’s marriage to Margaret signalled his rising status amongst the Gaelic leaders of Leinster. As a young man he had been excluded from receiving any stake in the midland plantations of 1563–4. He rapidly gathered support amongst the disaffected O’Connors and O’Mores and by the spring of 1571 had been elected ‘chief of his sept in Leix’.

By 1573 extreme violence was spiralling out of control in the midlands, as the O’Mores and other clans vigorously resisted the plantation of their lands. Although Margaret must have been familiar with life in a heavily militarised environment, her marriage to Rory Óg necessitated a courageous resolve on her part. She was relocating to a volatile war zone and could expect to lead a precarious and dangerous existence as the wife of a hunted man. Lord Deputy Henry Sidney exacerbated the increasingly fraught situation in the midlands by granting his captains wide-ranging powers; normal ethical restraints were abandoned, as acts of dubious legality gave rise to escalating levels of treachery and atrocity.

In October 1577 Sidney, accompanied by ‘excellent good executioners’, ambushed the ‘cabinish dwelling’ in which Rory Óg and his associates were holding two prisoners—Sidney’s son-in-law, Alexander Cosby, and his nephew, Sir Henry Harrington. Rory Óg and his marshall narrowly escaped with their lives. Margaret, her two young sons and other non-combatants were killed by Sidney’s forces, possibly after the engagement. The strength of Gaelic outrage at the news of Margaret’s death is evident in the notes of medical scribe Corc Ó Cadhla, who stated that she and other innocent people had been killed in contravention of contemporary rules of warfare:

‘… and with her have been killed women, and boys and humble folk, and people young and old, who according to all seeming, deserved not to be put to the sword’.

The Wicklow-based poet Donnchadh McKeogh, in reaction to her death, took the unusual step of criticising the O’Byrnes for arranging such a faraway match for their daughter. McKeogh also predicted that her murder would be avenged by the O’Byrnes.

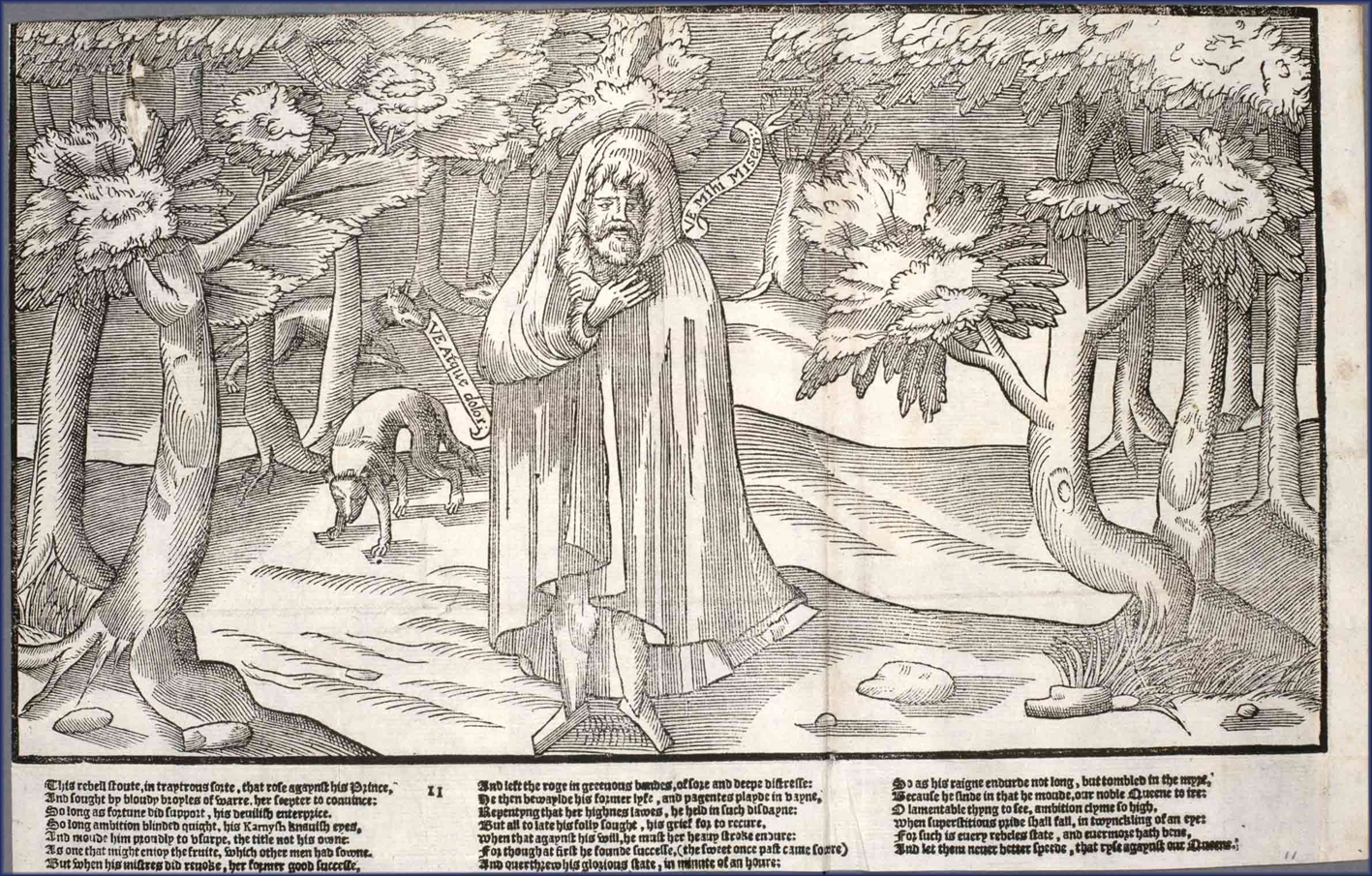

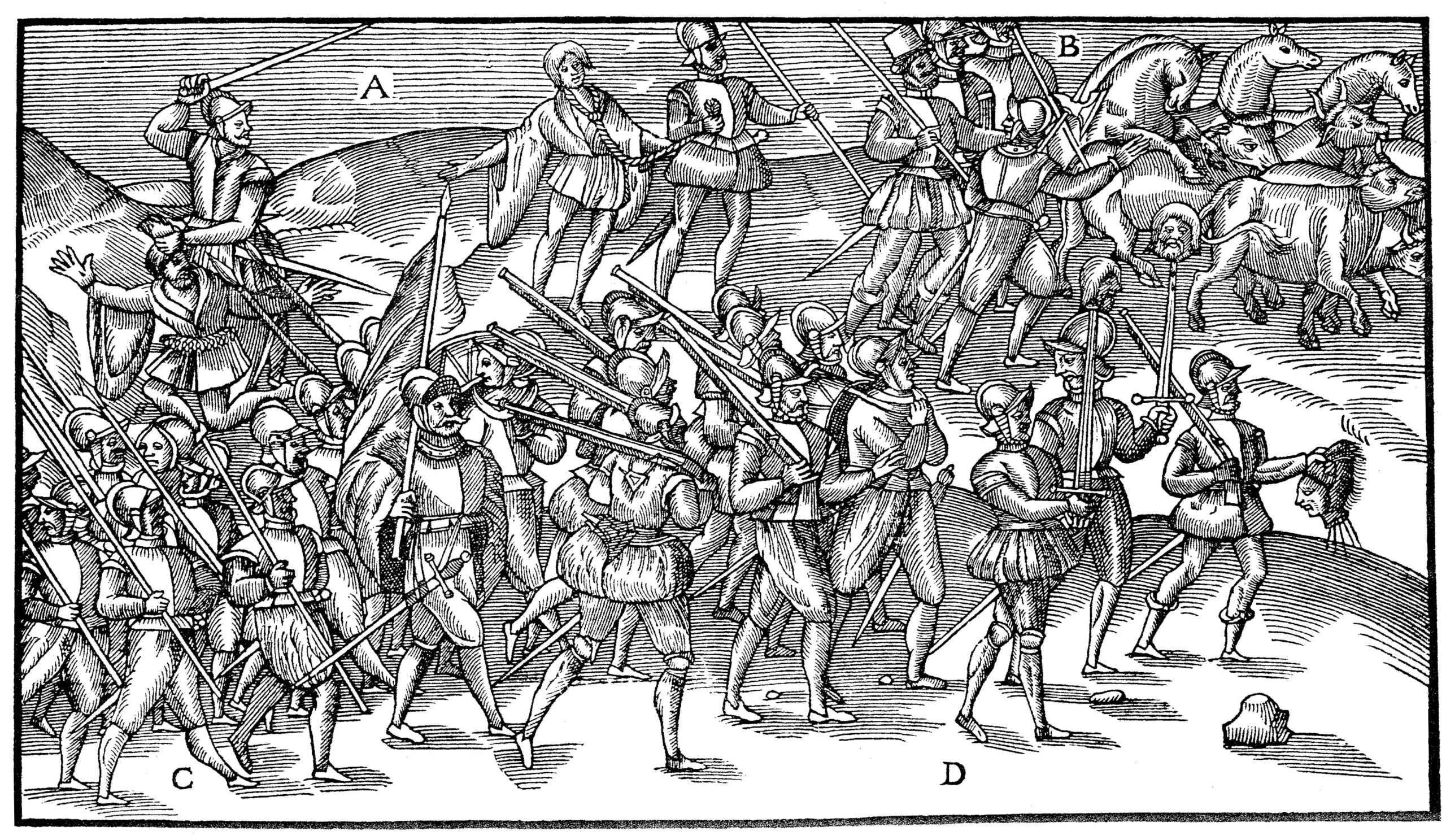

John Derricke’s The image of Irelande with a discourse of woodkarne (1581), a deliberately distorted and negative depiction of Gaelic Ireland, was commissioned in an attempt to salvage Sidney’s reputation. Derricke devotes 40 stanzas to lurid descriptions of Rory Óg; stanza 17 explicitly states that Margaret was executed by Sidney’s forces. Plate 5 of The image of Irelande (p. 27) illustrates a troop of Sidney’s soldiers carrying aloft two heads skewered on blood-splattered swords. The bottom right-hand corner depicts what appears to be a woman’s head being carried by the hair. Kenneth Nicholls suggests that the beheaded individual could be Margaret.

A few months later a notorious atrocity was committed at the rath of Mullaghmast, Co. Kildare. Unsuspecting and unarmed Gaelic leaders and their retinue from Leix (Queen’s County) were summarily slaughtered by English and loyal natives, with Sidney’s tacit approval. Sources differ as to the death-toll, but it may have been as high as 400 and resulted in the elimination of virtually all remaining native resistance in the midlands. Although Rory Óg fought on, he was eventually killed by a servant of the loyal Barnaby Mac Gillapatrick of Upper Ossory in July 1578. Rory Óg and Margaret’s surviving children, Uaithne (Owny) and Doireann, were brought up by their maternal uncle Feagh at Glenmalure.

SADHBH KAVANAGH

Feagh Mac Hugh O’Byrne’s wife, Rose O’Toole (d. c. 1629), is the most historically visible of the O’Byrne women. Much has already been written about her involvement in her husband’s political affairs. Marriage with Rose consolidated the ties between Feagh’s clan and the Castlekevin O’Tooles. Rose was not, however, Feagh’s first wife; he had previously been married during the 1560s to Sadhbh Kavanagh, daughter of Donall Mac Cahir, chief of the Kavanaghs of Garryhill. Both Sadhbh and Feagh were the great-great-grandchildren of Murrough Ballach Kavanagh, a late fifteenth-century king of Leinster. The couple had four sons and two daughters. Two of their sons, Phelim and Raymond, would go on to marry two of Rose O’Toole’s sisters, Úna and Katharine.

In October 1569, Feagh and his brothers rescued the rebellious Sir Edmund Butler (1534–1602) from Dublin Castle. Sir Edmund was the second son of James, 9th earl of Ormond, and a brother of Thomas, the 10th earl (c. 1531–1614), known as ‘Black Tom’. The power and prestige of the Butlers had grown in previous decades, reaching its peak under Black Tom, who dominated affairs in Elizabethan Ireland. Feagh’s wife Sadhbh commenced a liaison with Sir Edmund, possibly while he sojourned at the O’Byrnes’ stronghold during the winter of 1569–70. Their relationship ended Feagh and Sadhbh’s marriage; it seems to have been an amicable parting, although the scarcity of references to Sadhbh in Feagh’s poem-book may signify his private displeasure.

SADHBH KAVANAGH’S OTHER SON

No record has been located of Sadhbh Kavanagh’s subsequent marriage to any other Gaelic chieftain. As it happened, Sir Edmund was already married in the eyes of the Church to Eleanor Eustace, daughter of an Old English family, and they had at least three sons, Piers, James and Theobald. William F. Butler traced various Butler family pedigrees and published his findings in 1929. One such pedigree located in the Carew Manuscripts at Lambeth Library assigns several ‘natural’ children to Sir Edmund and describes ‘an illegitimate son, Thomas, living 1600’, naming his mother as ‘Pheagh McHughes wyfe’. Based on available evidence, it is reasonable to conclude that Sadhbh lived with Sir Edmund as a second wife or concubine. It is possible that Sadhbh’s relationship with Sir Edmund aligned with the political objectives of her own family, the Kavanaghs of Garryhill. If Feagh harboured any enmity towards Sir Edmund, it does not seem to have extended to the next generation. During the Nine Years War (1593–1603) ‘the bastardly boy … Thomas Butler FitzEdmond’ sought to be commended to the earl of Tyrone and entered into confederacy with his Butler half-brothers, James and Piers, and his Gabhal Ragnaill half-brothers, their father Feagh and Owny O’More.

Thomas Butler survived the Nine Years War. His half-brother, Theobald Butler (Sir Edmund’s only surviving legitimate son and the heir to the Ormond earldom), conveyed a sizeable proportion of his father’s estate to his ‘base brother’ Thomas, against the wishes of his uncle, Black Tom, the earl of Ormond. In 1628, during the reign of Charles I, Thomas was created 1st Baronet Butler of Cloughgrenan, Co. Carlow; the baronets of Garryhundon and Ballintemple are his descendants. Sustained and friendly relations seem to have been maintained between Thomas and his half-brother and Feagh’s successor, Phelim O’Byrne. The records indicate that on 2 January 1630 Phelim nominated his ‘well beloved brother, Sir Thomas Butler, Knight Baronet’, as executor of his last will and testament.

CONCLUSION

The laconic nature of the records obliges us to seek out the presence of our three women in important events as they occur in the more public lives of their male relatives. O’Byrne marriages were arranged to secure political benefits and the acquisition of military support. The complex nexus created by the marriages of just three O’Byrne women serves to demonstrate the extensive, fluid and multi-faceted nature of the clan’s alliances. High-status women were indoctrinated from a young age to accept their filial obligation to consent to such arrangements. Nonetheless, serial marriage and divorce-at-will must have meant considerable personal stress for women such as Sadhbh O’Byrne, not to mention familial instability for all concerned. Furthermore, in a society where divorce could be practised with such ease, ties between a conjugal pair may not have been strong.

In Margaret’s case, her life was endangered when she became a pawn in a dangerous political and military conflict. Yet we must resist any tendency to view these women as victims. They played an important role in cementing social cohesion and affinal bonds in a stateless society that lacked any form of central political authority. Ciaran Brady places the ‘impulse to subordinate and at times to negate’ their role in a broader context, arguing that this tendency was ‘by no means historically unique and arises from forces far deeper than the conditions prevailing in sixteenth century Ireland’. We lose sight of Sadhbh Kavanagh following her separation from Feagh, although sources reveal that through her son Thomas she became the unacknowledged matriarch of a branch of the Butler family.

Some insights have been gained from these three case-studies, yet many questions remain unanswered. Having conducted this research, my thoughts echo those of Clodagh Tait, who, in respect of another group of women from another past, ruefully reflects on the extent to which ‘we are left to wonder and worry about what happened to these women’.

Cora Crampton is secretary of West Wicklow Historical Society and the current holder of the Lord Walter FitzGerald medal and prize for original historical research.

Further reading

W.F. Butler, ‘The descendants of James, ninth earl of Ormond’, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 19 (1), 29–44.

M. MacCurtain & M. O’Dowd (eds), Women in early modern Ireland (Dublin, 1991).

K.W. Nicholls, Gaelic and Gaelicized Ireland in the Middle Ages (Dublin, 2003).

O’Byrne, War, politics and the Irish of Leinster, 1156–1606 (Dublin, 2003).

See https://www.tcd.ie/history/irishclansandchiefsprize.php for information on the Irish Chiefs’ and Clans’ Prize in Gaelic History 2025.