By Margaret Ward

During the suffrage years, feminists on both sides of the Irish Sea had cooperated on campaigns for the vote, despite not always agreeing on broader constitutional issues. By 1920, with the intensification of the War of Independence, British feminism became increasingly concerned about the reprisal policy being pursued by Crown forces. The Manchester branch of the Women’s International League for Peace sent a fact-finding delegation to Ireland, which on its return called for

‘The immediate liberation of Irish political prisoners and the offering of a truce during which all armed force shall be withdrawn and the keeping of order placed in the hands of Irish local elected bodies, thus creating conditions under which the Irish people may determine their own form of government’.

BRITISH FEMINISTS AND IRELAND

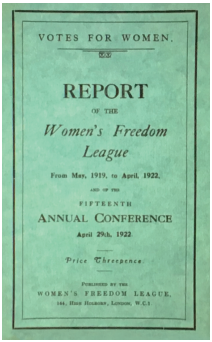

In January 1921 the Irish Women’s Franchise League invited Charlotte Despard, veteran feminist, pacifist and socialist, founder of the Women’s Freedom League (and sister of Lord French, lord lieutenant of Ireland between 1918 and April 1921), to see the situation at first hand. Despard and Maud Gonne travelled through the south-west, all under martial law, accumulating evidence of atrocities. In May 1921 the annual conference of the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) passed an emergency resolution instructing the executive to organise a ‘Women’s Procession of Protest’ to express their ‘strong disapproval of the methods adopted by the government in Ireland’. On 2 July 1921, 10,000 people took part in a demonstration through the West End of London, organised by the League and attended by members of all political parties. Speaking at Trafalgar Square, Despard urged Britain to withdraw its arms: ‘Let the great heart of England respond to the great heart of Ireland and then there would be peace’. The following resolution was passed:

‘This Mass Meeting convened by British women calls for the immediate cessation of strife and warfare between England and Ireland, the establishment of peace and concord, and an agreed settlement on the only possible basis of friendship and goodwill’.

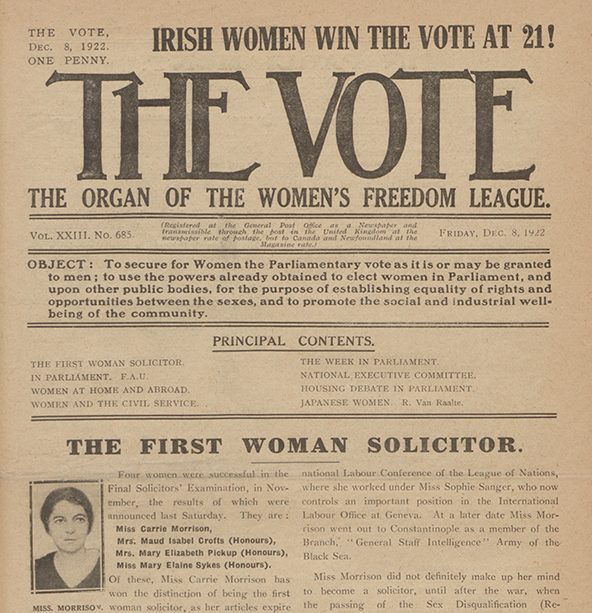

Despard moved to Ireland, identifying with the republican cause, while maintaining her pacifist beliefs. She remained in contact with her comrades in the WFL, often influencing the coverage of Ireland in its paper, The Vote, which was published as a collective enterprise. British feminism supported limited independence for Ireland as a dominion within the British Empire. Their chief interest related to issues specific to women in the Treaty settlement. What was happening in Ireland could, they hoped, have positive repercussions regarding the political status of women in Britain.

The Woman’s Leader, linked to the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, had been strongly anti-Home Rule and sympathetic to unionism in its earlier, pre-war, guise of The Common Cause. It was now edited by Ray Strachey, formerly a prominent non-militant suffragist, while its ‘Westminster correspondent’ was responsible for most of its Irish coverage. Another paper to take an interest in Irish affairs was the Workers’ Dreadnought, edited by Sylvia Pankhurst and closely aligned to the Communist Party. Despite Pankhurst’s previous militant feminism, the Dreadnought viewed Irish events solely through assessment of working-class militancy and the creation of workers’ soviets. Pankhurst had no interest in franchise issues. Bourgeois nationalists were ignored, with only Constance Markievicz receiving praise for her support for a workers’ republic. The Irish Labour Party was condemned for not building ‘an independent revolutionary movement working directly for a Soviet Republic’, choosing instead the ‘path of peace and the Downing Street Treaty’. The overriding message of the Dreadnought was that the national struggle had to end ‘in order that the class-consciousness of the workers may develop unchecked’.

EQUAL FRANCHISE AND THE TREATY

One crucial issue was the need to win votes for women under 30. The Representation of the People Act of 1918 had been only a partial victory. Irish women from numerous organisations formed delegations to plead their case. The Woman’s Leader reported on deputations sent by the Irish Women’s Franchise League, the Women’s International League, the Irish Women Workers’ Union and Cumann na mBan to de Valera and Griffith during February 1921. De Valera was reported to have ‘expressed sympathy with the views of the deputation and referred to the possibility that Dáil Éireann might take action in the matter’. The Vote quoted Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, who asked Griffith ‘for a pledge of support that a decree of the wider franchise might be unanimously adopted’, while he retorted that ‘he intended to allow no further obstruction designed to torpedo the Treaty and to prevent the will of the people being taken upon it’.

The Woman’s Leader reported on the Dáil debate on the franchise on 2 March 1922, when Deputy Kate O’Callaghan unsuccessfully introduced a motion calling for Irish women to be admitted to the franchise on the same terms as Irish men. Their Westminster correspondent attempted to proffer a neutral view on the debate:

‘Opinion will be divided as to the justice of Mr Griffith’s argument … but all who are suffragists first and party politicians afterwards will regret that the opponents of the Treaty would not allow the amendment which would have definitely and officially committed the Provisional Government to equal franchise to be passed’.

This was not wholly accurate, as a pledge had been extracted that women over 21 would have the franchise after the election, once the Irish Free State came into existence.

An Equal Franchise Committee in Britain argued that young women had undertaken much of the wartime work during the Great War but were still disenfranchised. The likelihood of Irish women gaining equal political representation before British women was a galling prospect that was referred to repeatedly. Shortly after the Dáil debate, Lord Robert Cecil introduced an Equal Franchise Bill to the House of Commons. It was unsuccessful. In condemning the inferior position of women in Britain, the WFL, writing to the prime minister, expressed a strong sense that British superiority was being undermined:

‘British women will keenly resent having less representation in the government of their country than the women of the Irish Free State, or than the women in those of our Colonies and Dependencies where women are enfranchised on the same terms as men’.

An attempt by the Provisional Government to water down the equality clause in the constitution was successfully resisted by Irish feminists, who sent word of their campaign to the British papers. Ernest Blythe had put forward an amendment limiting ‘equal rights as citizens’ to ‘equal political rights’. In response, a circular urging restoration of the original clause was signed by 50 representative women and sent to every member of the Dáil. The Woman’s Leader commented, with excessive optimism:

‘The fabric of the State, rising steadily amidst all the difficulty and confusion, is founded on the broad basis of equality and justice between men and women. It is a good omen for the future.’

As the Irish Free State Constitution Bill had to pass through three readings in the British House of Commons and House of Lords, Labour MP William Lynn took the opportunity at question time to ask, ‘in view of the unanimous approval given to such a measure … would the government introduce a bill next session which would concede the same right to all men and women in Great Britain at the age of 21?’ The prime minister’s curt reply was that ‘he was not prepared to adopt the Hon. Member’s suggestion’.

JUNE 1922 GENERAL ELECTION

Following the Irish general election of 16 June 1922, John Humphreys, secretary of the Proportional Representation Society, wrote to The Vote to claim that PR had turned the election

‘… into a most wonderful revelation of the mind of the people of Ireland … the moral force of public opinion clearly expressed must act as a powerful deterrent to military action on the part of a minority. It may be this minority may have to be put down by force, but the situation is much less difficult than it would have been if there had been but a sham election.’

The WFL claimed that if PR had been used for the British general election of November 1921, 50 women rather than two could have been returned as MPs.

The Woman’s Leader was quick to assert that the fact that only two women were returned in the election (Mary MacSwiney and Kate O’Callaghan, in strongly anti-Treaty constituencies) could not be viewed as a defeat for feminism but rather as an indication that other considerations were at play. They regretted that no party other than the republicans had stood women as candidates and looked forward to the result of the next elections, when adult suffrage would be instituted, with the ‘national question … by that time less difficult and uncertain’. Both the Woman’s Leader and The Vote congratulated the four women nominated for the Senate, The Vote adding that the victory ‘makes our own position of political inferiority in England, Scotland, Wales and Ulster [sic] the more galling, and the more strikingly unfair. It hastens the day when these fetters must be swept away.’ (In Britain and Ireland only women in the Free State could sit in the upper chamber. Women who were hereditary peers were unable to sit in the House of Lords until the Life Peerages Act of 1958. In Northern Ireland Marion Greeves became the first woman to be elected to the Senate in 1950.)

FEMINISM AND THE CIVIL WAR

British feminism was firmly on the side of the Provisional Government of Collins and Griffith, although this was phrased in somewhat patronising tones in the Woman’s Leader:

‘… everyone here wishes well to Mr Griffith and Mr Collins. We do not want to see difficulties in Ireland, even for the pleasure of showing to the world how intractable a people they are. We would rather, in this instance, say anything than “I told you so”, because we do really wish for a settlement of the troubles of that land.’

After anti-Treaty forces established their headquarters in the Four Courts, the Woman’s Leader supported military action: ‘If civil war had to come, it was as well that it should come quickly. But it is a terrible thing.’ The work of women in Ireland forming peace delegations to meet with leaders on both sides of the divide, urging dialogue rather than war, was not reported.

Coverage in The Vote was more nuanced, although members of the WFL often referred to Ireland as ‘the Isle of Unrest’. Speaking in London in June 1922, Despard remained hopeful that the Treaty ‘would eventually become the basis of a better understanding. The war in Ireland was not a religious war, but a political and economic struggle.’ Her New Year message of 1923, after six months of civil war, was more despairing: ‘… our world is so shattered—such terrible deeds are being done—such misery endured’. Yet her belief in women’s power remained strong: ‘We, in this distracted land, are gathering ourselves together to achieve the peace we have not yet. This is—that must be—women’s work, always.’

Dora Mellone, English-born former secretary of the non-militant Irishwomen’s Suffrage Federation, had moved from Warrenpoint to County Dublin, writing reports for both The Vote and the Woman’s Leader. (Irish feminism no longer had a newspaper, following the closure of the Irish Citizen in 1920, so British outlets provided a limited alternative.) In early 1923, writing for The Vote, Mellone insisted that in many parts of the country life went on as usual, while acknowledging that ‘the surface is very troubled at times, but underneath is the strong and steady current making for peace’.

Nevertheless, The Vote also carried a report from Dorothy Macardle (‘Girls in Irish Prisons’) on the position of the 400 republican women in jail because of their support for the anti-Treaty forces: ‘We feel we cannot do other than call attention to, and protest against, cruelties and abuses under which our sisters and fellow subjects are suffering in the Irish Free State today’.

AUGUST 1923 GENERAL ELECTION

In the Free State election of 27 August 1923, women over 21 were finally able to vote. Whether the new electorate had voted republican, whether women had supported the female candidates and whether PR had played a positive role were important issues. Again, there were subtle differences in interpretation of the results. In the Woman’s Leader Mellone asserted that ‘The Treaty is perfectly safe’, while acknowledging that some used PR to give second or third preferences to opposition candidates, citing the ‘Flogging Act’ as one reason for preferences going against the government. Although five women (four republican and one pro-Treaty) were elected, she concluded that ‘Feminism had little to do with the matter in any case’. For The Vote, she wrote more circumspectly that it was not surprising that Mrs Brugha headed the poll in Waterford, as she was ‘the widow of an admired fighter on the republican side’, adding that the effects of universal suffrage ‘cannot be traced accurately as yet’. Elsie Morton MBE, also writing for The Vote, declared that Madame Markievicz and Mary MacSwiney ‘had almost sensational victories’, but that these were ‘probably personal as well as party’. PR had enabled both majority and minority groupings to obtain their fair share of the votes, and ‘PR has told us again what Ireland thinks about the Treaty’. Two weeks later, writing again for the Woman’s Leader, Mellone gave her final assessment: ‘the result hardly points to the existence of a revolutionary spirit among the young women’.

Margaret Ward is Hon. Senior Lecturer in History at Queen’s University, Belfast, and author of Unmanageable revolutionaries: women and Irish nationalism 1880–1980 (Arlen House, 2021).

Further reading

G. Bell, Hesitant comrades: the Irish revolution and the British labour movement (London, 2016).

C. McGing, ‘Women’s political representation in Dáil Éireann in revolutionary and post-revolutionary Ireland’, in L. Connolly (ed.), Women and the Irish revolution (Dublin, 2020).

M. Mulvihill, Charlotte Despard, a biography (London, 1989).